|

In this week that saw the world celebrate International Women's Day, the InnovaSpace team welcome news about the work of Dr Lucia Hartmann & Jasmin Mittag, with a new concept for the shape of future space travel and a desire to promote equality - an ethos we fully support! The "Vulva Spaceship"

The first spacecraft in a V-shape is not only a symbol for more diversity in space, but also state-of-the-art and thus more sustainable. The “Vulva Spaceship” designed by “WBF Aeronautics” represents inclusivity, varying from the traditional shapes. Thus, the project adds another dimension to the representation of humanity in space and is communicating to the world that anyone has a place in the universe, regardless of physical characteristics. Dr. Lucia Hartmann, Head of “WBF Aeronautics” and inventor of the “Vulva Spaceship” reports from her research: “The spaceship’s shape is surprisingly aerodynamic, creating way less drag when the vehicle punches through the Earth’s atmosphere. Due to this optimized V-shape, it guarantees maximum fuel efficiency with an exterior made of reinforced carbon which enables it to withstand the most extreme temperatures.” “WBF Aeronautics” wants to inspire space travel to be open to modern forms and to realise equal opportunities across the universe. The Project "WBF Aeronautics"

“WBF Aeronautics” is a collaboration between Dr. Lucia Hartmann and her team and “Wer braucht Feminismus?” (WBF). Dr. Lucia Hartmann started her research work about spaceships and discovered that a spaceship varying from traditional shapes, would be more aerodynamic and create less drag, thus being more sustainable. She reached out to us for the purpose of a collaboration and for us to do the media work as there is much more to it than just the scientific aspect. On the one hand, the topic is sensitive, but on the other hand, it also holds great opportunities. The symbol of a Spaceship in a V-shape represents more diversity in space. The project adds another dimension to the representation of humanity in space. We believe that equality even has a place in space. It’s time for new symbols in the universe. This blog is promoted and supported by the:

Os autores são membros do time da InnovaSpace e possuem vasta experiência profissional em medicina de aviaçāo e fisiologia aeroespacial - ensino, pesquisa e inovaçāo.  O Problema Emergências médicas durante voos comerciais de curta ou longa duração, nacionais ou internacionais, estão se tornando cada vez mais comuns. Isso se deve a fatores já conhecidos, como a expansão da indústria da aviação, a popularização dos voos comerciais e a maior diversidade do perfil do viajante, incluindo passageiros idosos, portadores de doenças crônicas ou usuários de medicações. Junta-se aqui o próprio ambiente de cabine, que impõe, por exemplo, o estresse da hipóxia hipobárica, dos disbarismos pela expansão de gases de cavidades corporais, da exposição ao ar frio e seco, a ruídos, a vibrações e a acelerações, da alteração do ciclo circadiano, da fadiga e da imobilidade. Esses fatores afetam pouco ou nada os organismos sadios, mas podem ser danosos em diferentes graus ao passageiro idoso e/ou portador de doenças crônicas. A Situação Exemplo 1 – Uma avaliação clínica ou pré-operatória - Quando o motivo de uma consulta médica é uma avaliação clínica ou pré-operatória, deve-se questionar e considerar vários aspectos durante a anamnese, o exame físico e os exames laboratoriais, para se chegar a melhor decisão clínico-cirúrgica possível, reduzindo ao máximo possíveis eventos adversos, minimizando desfechos não desejados e otimizando a segurança do paciente no voo. Assim, uma pergunta não deve faltar na anamnese - “Existe o plano de uma viagem aérea num futuro próximo?”. Para que esse questionamento, no entanto, produza um impacto positivo na tomada de decisão, é mandatório que o médico assistente detenha conhecimento sobre as condições estressantes do ambiente de cabine de uma aeronave e as condições do passageiro enfermo, objetivando discutir o planejamento de um voo seguro ou até mesmo o cancelamento ou postergação do mesmo. Exemplo 2 – Médico a bordo? – Incidentes médicos com passageiros em voos comerciais vêm se tornando mais comuns. No entanto, o ambiente de cabine e os recursos médicos disponíveis a bordo de aeronaves são quase sempre de total desconhecimento dos médicos que se tornam voluntários no atendimento a um passageiro durante um voo comercial. Sistemas de auxílio às tripulações a ao médico voluntário incluem o uso da saúde digital e da telemedicina, as quais, nem sempre estão disponíveis para orientação num incidente médico a bordo. Ainda, muitos casos poderiam ter sido evitados, se, durante a avaliação pré-voo por parte do médico clínico, especialista ou cirurgião, fosse incluído na anamnese do paciente questionamentos relativos a planos de viagens de avião. A Solução A InnovaSpace vem adovagar em favor do ensino da Medicina de Aviação e da Fisiologia Aeroespacial na formação de estudantes de faculdades de medicina, através da inserção de uma série de aulas constituindo disciplinas curriculares novas ou integrando disciplinas já existentes no currículo acadêmico. Esta iniciativa é apoiada pelas Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Aeroespacial (SBMA) e

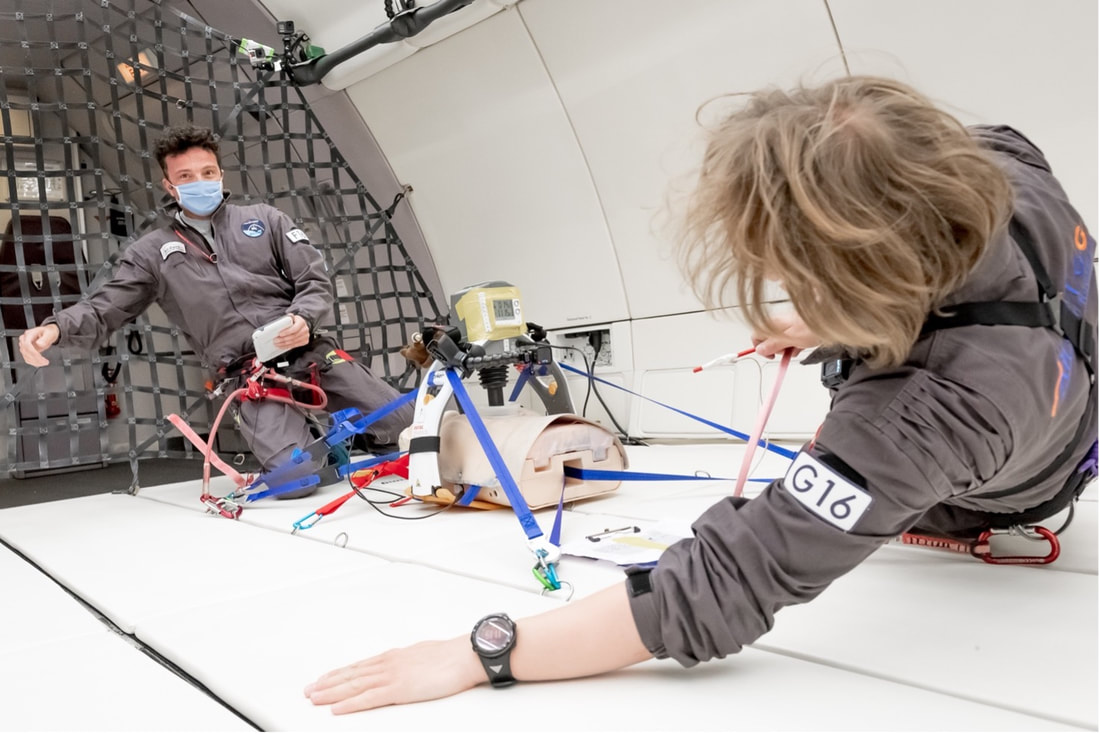

Sociedade Portuguesa de Medicina Aeronáutica (SMAPor)  Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons If someone asked you – “what do you want to do when you become an adult?" – what would your response be? Now, imagine me as a 14-year-old student at an art school, and one day going to a Red Cross course and recognizing that you love the idea of the First Rescue and Emergency services. My first answer was always – Astronaut! But… what should I do now? Astronaut or Doctor ...? Solution? Helicopter flight physician! But how can I do this thing…is it possible? Yes, it is! I first studied medicine and became an anesthetist and intensivist. And so it was… once I graduated and then specialized in anesthesia, I began to frequent the world of Helicopter Rescue. A fantastic job that combines flight, wonderful landscapes (the Dolomites ...) and the human factor. A lot of different situations every day and in different places. The helicopter flight physician is responsible for providing casualties with emergency medical assistance at the accident site, as well as attending to patients during primary and secondary missions. The scope of activities also involves recovering patients from topographically difficult terrain by means of a rescue hoist. This applies exactly from the time the patient is put into your care until you hand them over to the medical staff responsible at the destination hospital.  LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions I remember one early afternoon in September 2013, the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) Dispatching Centre of Treviso, Italy received a call from a person who told the operator that her cousin, a 53-year-old man with a previous history of inferior myocardial infarction, had suddenly fallen down while walking at home. While dispatching the nearest ambulance, the dispatcher provided CPR pre-arrival instructions to the caller, according to standard protocols. An EMS helicopter, staffed by an emergency physician (namely, me!) and a nurse, was dispatched to the scene. The first emergency unit, staffed by a nurse and an emergency technician, reached the patient within 10 minutes of the call and found the woman performing chest compressions as instructed by the dispatching center operator. My team in the helicopter reached the patient 10 minutes after the first unit started ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support). The cardiac rhythm was a persistent ventricular fibrillation and the decision was made to apply a LUCAS-3 chest compressions device to the patient, who was then transported directly to the hospital and catheterization laboratory. Selective percutaneous coronary angiography was performed with ongoing continuous mechanical chest compressions. Coronary angioplasty was performed on two coronary arteries. Five days after resuscitation, the patient was extubated and was alert and oriented. After 16 days he was discharged from the Intensive Care Unit and transferred to a post-intensive care unit. The patient survived without any neurological damage despite prolonged resuscitation and a call-to-ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) interval of nearly 2 hours. The immediate beginning of chest compressions by the caller and uninterrupted CPR by medical teams preserved the brain from ischemic damage. The mechanical chest compression device permitted safe and effective CPR during helicopter transportation directly to the catheterization laboratory, which permitted the removal of the coronary artery occlusions, which were preventing the ROSC. This is why I think this is an amazing job… A little about the author: Alessandro Forti As well as being a certified specialist in Cardiac-Anaesthetics, Intensive Care Medicine and Aerospace Medicine, currently working as an intensivist, cardiac-anesthesiologist and HEMS doctor in northern Italy, Alessandro has a passion for space clinical medicine, which began in 2012 following a post-graduate course in Space Medicine at the San Donato Milanese University. He has been involved in space medical research as a COSPAR (Committee on Space Research) collaborator and acted as a reviewer of many scientific articles for the journal Advances in Space Research (Elsevier). He was also Coordinator of the HEMS base in Pieve di Cadore-Italy from 2018-2020. Alessandro is Principal Investigator for the research Mechanical Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Simulated Microgravity and Hypergravity Conditions: a manikin study, which took place during the 4th. parabolic flight campaign in Dübendorf (CH) in June 2020, in collaboration with the SkyLab Foundation, CNES and DLR. His main areas of interest are space clinical medicine, CPR in different environments (mountain, avalanche victims, hypothermia, hyper and microgravity), ongoing CPR with ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) neuroprotection and neuromonitoring during DHCA (Deep Hypothermia Cardiac Arrest) in Cardiac Surgery.

Vladimir PletserDirector of Space Training Operations, Blue Abyss; European Space Agency (Retd); Chinese Academy of Sciences (Retd); InnovaSpace Advisory Board Member Congratulations to Editor Vladimir Pletser and all the authors who contributed to this interesting open-access book entitled Preparations of Space Experiments, which was published this week. Spend a few minutes watching Vladimir as he summarises the contents of each chapter, written by world-leading researchers who have designed and prepared science experiments on microgravity platforms, including aircraft parabolic flights, in preparation for subsequent spaceflight. Mary UpritchardInnovaSpace Co-Founder & Admin Director

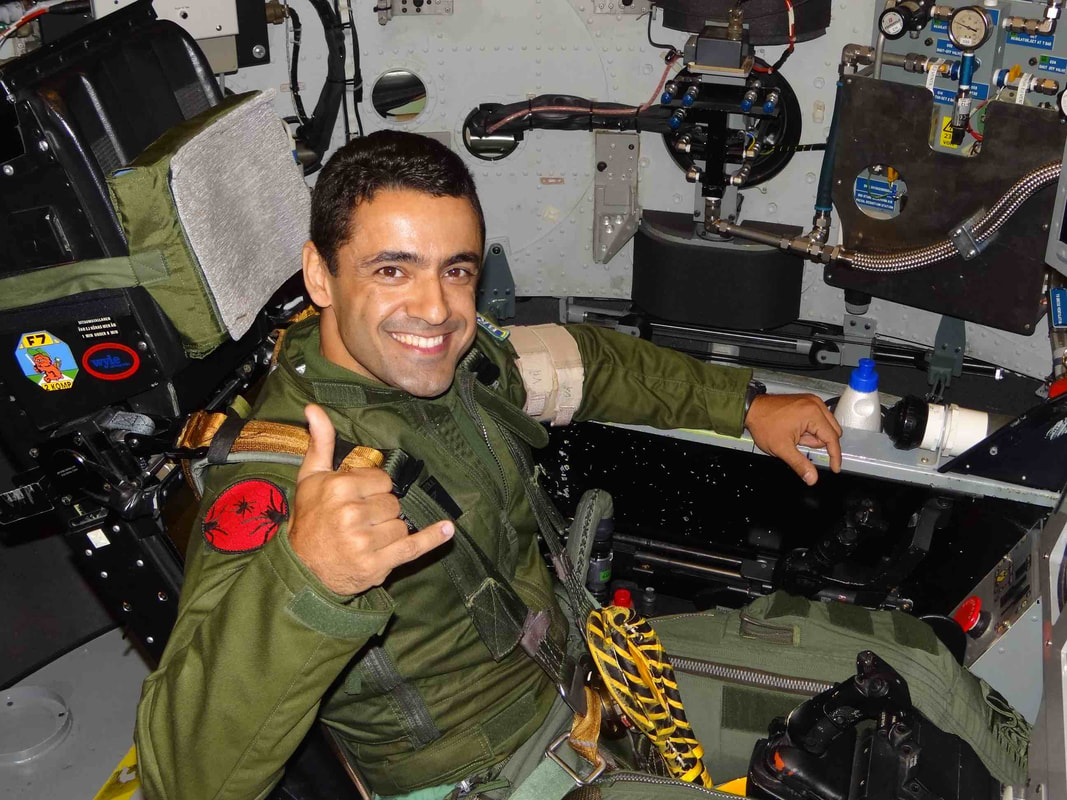

Author: Thaynara Vicente B KurrleSuccessful International Baccalaureate Diploma candidate; Ketedralskolan, Linköping, Sweden & now studying medicine  For as long as I can remember, I have always been flying around. My mother was a flight attendant, my father was an Air Force mechanic and we spent most of our lives living in an Air Force base. To board, deplane and wake up with the noise of helicopters and jets was part of the routine, which did not make it less special to me. When I was 17 years-old, my family was transferred to Sweden and I had to decide what I wanted to do with my life. I was only sure about 2 things: I wanted to help and serve people, and I loved airplanes and the life in the air. How was I supposed to combine these two? I had no idea. Most people did not see a link between these two points, but I knew that I had to find a way, otherwise, I would never feel complete. If I would imagine myself permanently away from jets and airports or not in direct contact with people in need, a huge void would open in my chest; it just was not right, “either, or” was not an option to me. In a Spring afternoon of 2018, I overheard some fighter pilots telling stories about accidents they had witnessed: a smashed jaw during the ejection after a period of temporal distortion, tunnelled vision, and a total blackout during the centrifuge training. Then, it hit me, those people were the link, they were the ones who connected those amazing machines to the human factor, they were the ones I wanted to help. I started to research, and I still remember the first words that caught my eyes: “flight-surgeon”, “AsMA”, “Aerospace Medicine”. Upon reading the last mentioned, my heart dropped. I had found it. I had found an entire field and community of people as curious as me and that shared the same passions. And at the end of that year I was given the chance to get in touch with it more directly. To graduate the International Baccalaureate (a different kind of high school), every student must carry out an independent research about a topic they would be interested in studying in university, our first research paper. I knew exactly what I wanted to do, I wanted to understand the symptoms and episodes I had heard about countless times, I wanted to understand what that so feared G. was. I read all the books about aerospace medicine fundamentals and flight physiology I could find, I started to talk to every single crew member and engineer I could reach, but the understanding of the symptoms through medical lenses was still missing. Another important thing that was missing was a supervisor, who would be willing to help me to start the research. Basically, the Science Department of my school did not understand what I was going for, how I was going to do it and no teacher was exactly thrilled with the idea of supervising a student they had no idea of how to help. It was even hard to decide whether to classify it as a Biology or Physics project! It was in the spring of 2019 that Maria, who was not even my teacher, heard about the project and was willing to supervise me, but I would have to find help from doctors outside; as she put it “You have chosen a very, very specific topic, so you need a very specific knowledge because I can’t tell you how to start”. And here we go again on another quest for a supervisor. And this quest is what made me fall completely in love with the scientific community. Doctors who had never met me sent me PDFs and articles and two of them (thank you so much, Dr Suto and Dr Lia) sent me the contact of Dr Thais Russomano, who was the fairy godmother of my Extended Essay. She taught me how to structure and organise a research based on the study of the literature, how to select it, how to understand the state of the art of that field. It was more challenging than I was expecting but it made all the difference. Thanks to all her feedbacks and articles I was finally able to understand where I was and how far I would be able to go (unfortunately not as far as I wanted due to school limitations). But now I knew what I was doing. I wanted to understand the effects of the G-acceleration on the human cardiac system and how the Anti-G Straining Manoeuvre diminished its effects. All I needed for the school to approve it was: at least 7 volunteer pilots with enough availability to measure their blood pressure while doing loops 2 or 3 times for a random girl’s school project, piece of cake right? To my heart-stopping surprise I got all of them, and they were all mostly glad to help me and to send me papers, videos, and pictures from their own centrifuge trainings (thank you so much Major Forneas and Colonel Leite). Nevertheless, to my despair the data collected contradicted my primary hypothesis! Great!

That is when my dear friend Jonas comes into scene. He worked at SAAB, the company which was developing the new Brazilian Grippen, state-of-the-art fighter jet, and offered to arrange me an interview with a test-pilot. It was by far, one of the greatest days of my life! While we were waiting for Andreas to finish his debriefing, Jonas took me on a tour around the Flight Test Centre. I had always wanted to see the Grippen; only one was ready so far, it had flown only once and only authorised personal could see or get close to it, or at least I had been told. Jonas opened the hangar’s door and there it was! The mysterious Grippen and I was one of the few civils, who had nothing to do with the project whatsoever, who had been able not only to see it but to climb up to its cockpit! Right there, I knew I had made the right choice. Andreas, the test-pilot, still wearing his anti-G suit, spent a long time answering my endless questions, and by the time I finished the interview I understood where I had gone wrong and the kind of data that I needed to prove my new hypothesis right! And again, I was mesmerised by how the scientific community mobilised itself to help an enthusiast like me, who was still not even part of it.  Göttingen DLR School Lab Logo Göttingen DLR School Lab Logo Hi, my name is Edgard, I'm 12 years old and at the age of 9 years I participated for the first time in the InnovaSpace project "Kids2Mars", asking the question 'why is Mars red?'. I'm Brazilian, but I have lived in Germany since 2009 in the city of Göttingen. I'm now finishing sixth grade, and my 3 favourite subjects are Mathematics, Experiment Workshops, and Natural Sciences - oh and in fourth place comes English! Since September 2019, I have been participating in the Flugmodellbau Project (model airplane construction) at the German Aerospace Center (DLR) School Lab, building model airplanes - Macht Spaß! (it's fun!) Too bad it ended just before Christmas. But my history with DLR began much earlier, when we came from Brazil in 2009, as my father started his PhD at the DLR. As the months went by, our house became full of posters and materials related to spaceships, airplanes, and wind tunnels. There was always a new technology and he promised me that as soon as I was older, after all I was only 4 years old at that time, he would take me to participate in the DLR/School Lab (Photo 1). I never forgot what he said, and it's a good thing my dad didn't either! And so I discovered the DLR.  School Lab, in a deactivated Wind Tunnel School Lab, in a deactivated Wind Tunnel The years passed by and finally my time to participate came. After a long wait and never forgetting that world my father had introduced me to, I arrived in the sixth grade of school and with it came the offer to participate in after-school activities (every semester my school organises an extra activity, called "Club", involving sports and leisure activities). I have already done climbing, and currently I am doing gardening. In 2019 I signed up for the DLR, which once a year offers the option of building aircraft models. There were only a few vacancies but luckily, and with a little bit of divine help, I managed to enter. It was great and I started having activities at DLR every week. Some colleagues from my school (2) also participated in the project with me and I made new friends too at DLR, who came from other schools. Altogether there were 16 of us. I like the workshop, it has various tools and lots of things to assemble. Macht spaß! I began by assembling various model airplanes in paper and styrofoam to understand how aerodynamics work and how airplanes fly - a new model every week! I really like going to the DLR. The coordinator, together with the activity monitors (3) are really friendly and know how to teach things about airplanes well. I think this activity is important because I like airplanes, doing experiments and technology, and the DLR environment is really cool. I have already learnt very important things about physics, stuff that I don't even have at school yet. I've dedicated myself because I think it will help me in my education and it will be good for my life. I don't yet know what I will be when I grow up, for now I'm thinking about being an architect, a designer. In January this year, 2020, I began the second (advanced) module of the model airplane workshop because I wanted to continue learning. Only myself and 2 other colleagues continued on from the first module, joined by 3 new friends, making 6 of us in total. When I finish this module, I intend continuing on to the next one and, who knows, maybe enter the School Lab for real one day. I consider myself to be a normal child. I don't always like to go to school, I have hobbies like riding my scooter and playing video games. I like doing sports like badminton, swimming, running and walking. And I dream of winning the Lotto, buying a house and having a very peaceful life. The InnovaSpace Team

Quando se pensa em viajar de avião, a primeira coisa que vem à cabeça é o serviço de bordo e as opções de alimentação. Brincadeira! É a segurança, claro. Todo mundo quer decolar, viajar e aterrissar em paz. Mas, para que tudo possa acontecer de uma forma tão profissional que você nem perceba, muitas pessoas estão trabalhando nos bastidores. A tripulação – piloto, copiloto, comissários, técnicos – tem muita responsabilidade. Vivem uma rotina difícil de horas e horas no ar, com alguns intervalos no solo. Por isso, você já imaginou como é a saúde deles? Como fazem para ter corpo e mente saudáveis? E os passageiros? Será que todos estão em condições de voar? Esses questionamentos motivaram horas de estudo dos médicos Thais Russomano e João de Carvalho Castro, os quais dedicaram muito de sua vida acadêmica à medicina aeroespacial. E você tem a oportunidade de conhecer o trabalho deles em detalhes através do eBook "A Fisiologia Humana no Ambiente Aeroespacial".  Abaixo, um trecho do livro para que você possa se inspirar: "O sonho de voar sempre esteve presente no imaginário humano desde os tempos mais remotos. Atualmente, cruzar o mundo de um lado para o outro, aproximando pessoas, vencendo barreiras geográficas e integrando culturas, é uma realidade viável e acessível. O ambiente aeroespacial, porém, difere do terrestre e impõe vários riscos à saúde e à segurança de aviadores, da tripulação de bordo e de passageiros durante um voo." O eBook foi oficialmente lançado em 19 de Fev, na Ordem dos Médicos, Secção Sul, Lisboa, Portugal, com o suporte da Sociedade Médica Científica Aeroespacial - Associação Portuguesa (SMAPor). Os convidados tiveram ainda a oportunidade de assistir a três palestras. Na primeira, Thais Russomano debateu o tema "Fisiologia Humana no Espaço". Após, João Castro explorou aspectos ligados à "Fisiologia Aeroespacial". Por fim, a médica Rosirene Gessinger abordou o tema "Medicina de Aviação". O evento e o eBook são iniciativas da InnovaSpace, uma empresa britânica do tipo Think Tank, global e inclusiva, de caráter multicultural e multidisciplinar. A InnovaSpace atua nas áreas espacial, aeronáutica e em telessaúde. E tem uma missão educativa muito importante: fazer com que a ciência espacial seja democratizada, tornando-a um assunto comum ao maior número possível de pessoas mundo afora!

O livro pode ser comprado no site Smashwords. Registre-se aqui primeiro, faça uma pesquisa usando nome dos autores ou o título do livro para encontrá-lo. Compre e faça o download, como um arquivo epub ou mobi. Dr. Lucas RehnbergInnovaSpace Space Life Sciences Expert. Recently I had the pleasure to attend the world’s largest aerospace medicine conference in Las Vegas, the 90th Annual Aerospace Medical Association (AsMA) Conference. This was my second AsMA (@Aero_Med) meeting and it didn’t disappoint. As a doctor training in the UK with an interest in space medicine, the AsMA conference is a great opportunity to present work, meet other space medicine enthusiasts as well as individuals from different disciplines – but all with a shared passion for space and aerospace. The thought behind this blog was to serve as a taster of what AsMA has to offer to those thinking about pursuing a career in this field or who want to gain an idea of how to become involved. So, this was my experience of the conference: Day 1 - Monday

Started with an incredible opening session commemorating the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 and the moon landing. The panel was moderated by Dr Mike Barratt, astronaut and flight surgeon, and consisted of some giants from the Apollo missions: - Dr Charles Berry & Dr Bill Carpentier, Apollo flight surgeons. - Gerry Griffin, Apollo flight director. The session opened with a specially commissioned video dedicated to the Apollo 11 landing in 1969 and the lead-up time. It was an excellent reminder of what was achieved when a nation came together and set the tone for the discussion, reflecting on their experience of Apollo 11 and the Apollo missions. Some of my favourite moments of this session include when Dr Berry told a great story of stopping President Nixon from having a meal with the Apollo 11 crew the night before their launch, including a letter he wrote to President Nixon apologising for this. Then flight surgeon Dr Carpentier told us what flight surgeons learnt from the Mercury and Gemini missions, before starting on the Apollo missions. Dr Carpentier also spoke about some of his training, including practicing jumping from a moving helicopter in order that he could give medical assistance to the landing Apollo crews. Gerry Griffin spoke of the pressure of the Apollo missions and the relief mixed with excitement when the Apollo 11 crew set foot on the aircraft carrier after their landing. He also spoke about the Apollo 1 tragedy, what we learnt from all the Apollo missions, and how this will help human spaceflight now that we are focusing on going back to the Moon. Closing comments from each of the panel followed a similar theme, summed up best by Gerry Griffin, "We’ve gotta get back to the Moon. It’s been 50 years since we’ve done it...we need to get our mojo back." |

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed