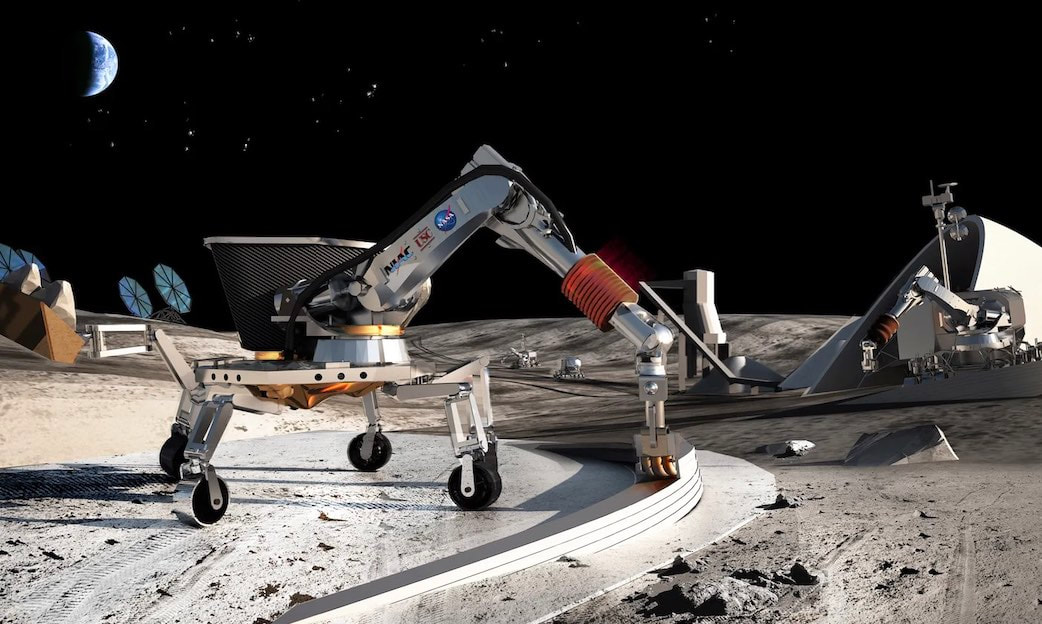

Author: Darrion K McNultyUndergrad student, Aerospace Engineering on the Pre-Medical track, Univ of Oklahoma; Project Manager, NASA's L'SPACE Mission Concept Academy; Future Pilot-Physician & Astronaut A review of original article - Building Robots For “Zero Mass” Space Exploration - written by Jacek Krywko (8th Feb 2024), published on the ARS Technica website The idea of exploring space without lugging around tons of gear sounds like something straight out of a sci-fi flick, but guess what? It might just be closer than we think! This article dives into the wild world of "Zero Mass" space exploration, where scientists are ditching the heavy payloads and instead relying on super-intelligent robots and nifty building materials. Think about it: sending stuff into space costs a fortune. Like a serious fortune. But what if we could cut down on all that weight and send up a bunch of self-replicating robots armed with super cool building blocks? That's the dream these NASA and Stanford folks are chasing. They're talking about using materials that can rebuild themselves, which is mind-blowing. It's like something out of a sci-fi novel from way back in the day. And get this - they're not just dreaming about it. They've built a bunch of these little building blocks called "voxels" and tested them out. These things are crazy vital but weigh next to nothing. So you can pack a bunch of them in your backpack and build whatever you need on the fly - like a shelter, a bridge, or even a boat! And here's the kicker - they're not just building stuff on their own. They've got these robots doing all the heavy lifting. These robots are like little construction workers, piecing together structures autonomously. It's like watching a futuristic version of a construction site! But it's not all just for show. They're thinking about using this tech to build towers on the Moon! Yeah, you heard that right. Towers on the freaking Moon! It's all about maximizing sunlight and getting the best communication signals. And with this tech, they reckon they can pull it off.

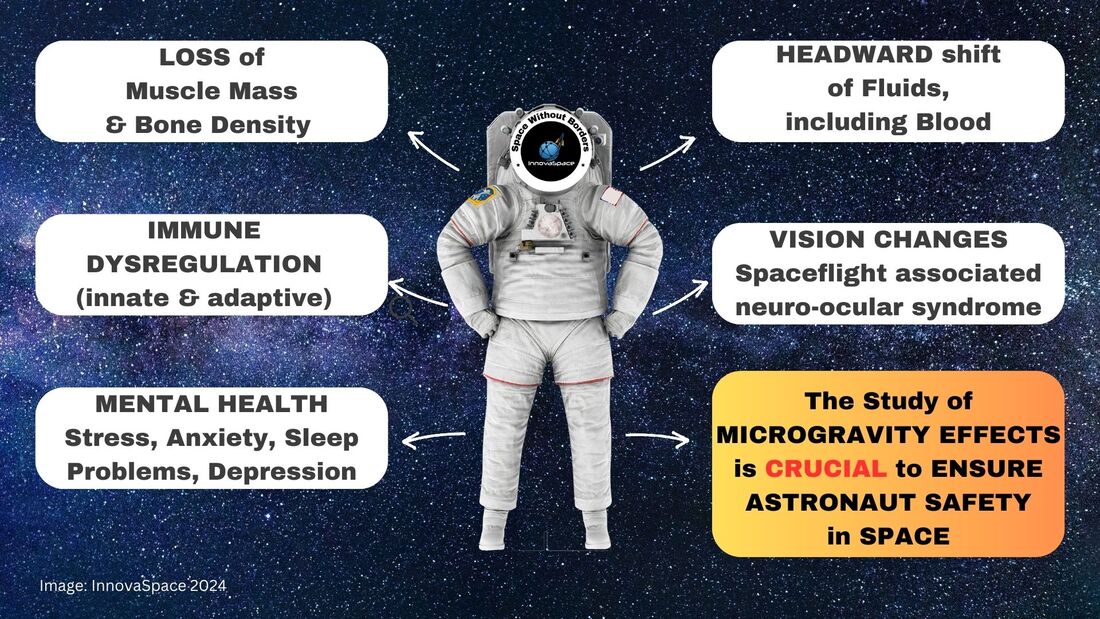

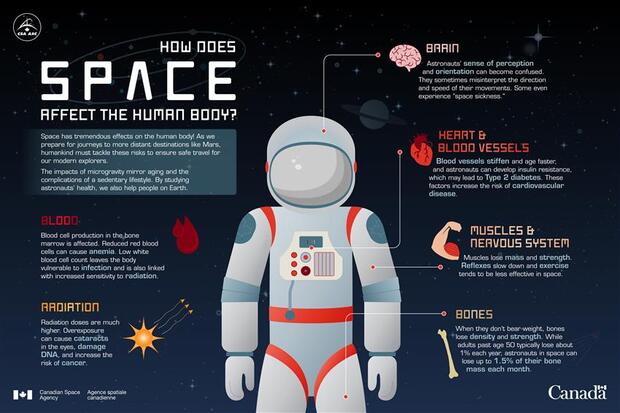

So, while we might not be hopping on spaceships and jetting off to distant planets just yet, it seems like we're getting closer every day. Who knows, maybe one day we'll all be living in moon towers built by robots. Hey, a guy can dream, right? Author: Leonardo PilattiPhysiotherapist | Currently taking Master’s degree in Space Medicine Microgravity is a fascinating topic when it comes to the study of astronaut health. When humans are exposed to microgravity, the effects on their bodies can be quite significant. One of the first things to understand about microgravity is its effect on the musculoskeletal system. In the absence of gravity, astronauts experience a decrease in muscle mass and bone density. The lack of load-bearing activity in microgravity leads to muscle atrophy and bone loss. This can result in decreased strength and increased risk of fractures once astronauts return to Earth. Another area of concern in microgravity is cardiovascular health. On Earth, gravity helps to pump blood towards the lower extremities. In microgravity, this effect is greatly reduced, causing fluids and blood to shift towards the upper body. This can lead to a decrease in plasma volume. Astronauts often have to undergo intense exercise regimes during their space missions to counteract these effects. The immune system is also affected by microgravity. Studies have shown that the immune response of astronauts is suppressed during spaceflight. This can make them more vulnerable to infections and diseases. Researchers are still studying the exact mechanisms behind this phenomenon and are trying to find ways to boost the immune system during space missions. Microgravity also has an impact on the astronaut's vision. Some astronauts have reported changes in their vision, such as an increase in visual blurring and other visual disturbances. This condition, known as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), is still being studied to understand its underlying causes and potential long-term effects. In addition to physical health, microgravity can also impact an astronaut's mental well-being. The unique environment of space, with its isolation, confinement, and lack of natural daylight, can lead to psychological challenges such as mood swings, sleep disturbances, and increased stress. NASA and other space agencies provide mental health support and psychological training to help astronauts cope with these challenges. To mitigate the negative effects of microgravity on astronaut health, space agencies invest in various countermeasures. These include exercise programs, special diets, and even medications. Additionally, researchers are constantly studying new technologies and strategies to protect and enhance astronaut health during long-duration space missions.

In conclusion, microgravity has significant effects on astronaut health, impacting various systems in the body. The study of these effects is crucial to ensure the well-being and safety of astronauts during space missions. By understanding and addressing these challenges, we can continue to push the boundaries of space exploration while also safeguarding the health of those who venture into the final frontier. Author: Dr. Paul ZilbermanMedical Doctor, Anaesthetist, Hadassah Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel

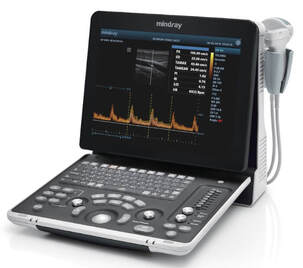

Space is very different, in many aspects. This post does not attempt to address the many changes the human body experiences in space, such as volume modifications in body compartments, fluid shifts, structural configuration in receptor* morphology and, as a consequence, possible variations in pharmacology response, etc. * For the lay reader, a receptor is a special structure on the surface of a cell, for example, that functions as a "receiving point" on which a chemical substance acts in a unique way (like a key – lock mechanism) and a specific reaction is generated (like a muscle contraction) or inhibited (like a cork closing a bottle and blocking the passage of a fluid). These complex structural changes modify many biological reactions, as well as the body’s response to medications. Rather, this post presents some of the technical challenges that an anaesthesiologist may encounter in space. Confined space. On Earth gravity keeps everyone’s feet on the ground. Different pieces of equipment can be repositioned depending on the procedure, machinery can be brought in as needed (XRay scans in orthopaedics, for instance), electric cables can be switched to other convenient wall sockets etc. In a fixed volume space capsule, you don’t have all these possibilities. Everything is measured for maximum volume efficiency. Taking into consideration that anything can and will float if not properly anchored, we can imagine what an “anaesthesia dance” could happen! What equipment? On Earth an anaesthesia workstation is always present in the OR. Depending on its complexity its volume can vary between a medium size fridge to a large double-doored one, just put on its side. You don’t have this amount of deposit in a space cabin, but let’s suppose for one moment that you do - you then need an Anaesthesia Gas Scavenging System (AGSS), which removes the anaesthesia gases that have leaked out or at the end of the procedure. On Earth, these gases are expelled into the atmosphere (there is a lot to talk about this and the greenhouse effects too) and the air currents around any medical facility carry them away. In space you don’t have this. Any gas must be expelled using energy, an active process. Otherwise, the whole cabin will become a big anaesthesia machine with all crew members affected. And, speaking of energy, an anaesthesia workstation is also powered by electricity, which is a limited resource in space, depending on the surface of the solar (or light in general) panels. This energy must be stored and used for other life maintenance systems as well, of which a critical example is the Sabatier reactor that provides oxygen. Regional anaesthesia The simplicity and portability of the necessary equipment makes this type of anesthesia attractive. For peripheral neural blocks all you need is a simple ultrasound machine and dedicated needles. The potential drawbacks are that the technique/s need to be taught on Earth but their “transposition” to space is a bit problematic. If the spinal/epidural anaesthesia is relatively simple to learn, the USG (ultrasound guided) blocks are more challenging. Furthermore, the bodily fluid shift due to the lack of gravity causes many tissues to change their tridimensional appearance, leading to increased difficulty in performing the block.

The cardiovascular responses that accompany spinal/epidural anaesthesia on Earth, in terms of heart rate and blood pressure, are different in space. There may be a lack of reactivity so a certain reduction in blood pressure, for example, might not be compensated. We need to remember that the hostile environment in space, especially radiation, affects not only the human body, but also many sensitive electronic components of medical equipment, leading to possible dysfunction. Monitors can potentially de-calibrate and all the information you receive may become inaccurate. Fluids Preparing and administering a fluid on Earth is routine, however, the lack of gravitation in space poses other challenges: air and fluids do not mix. It is called “lack of buoyancy”. Unless we use special equipment to separate fluids from air nothing can be delivered to the patient. This statement is true also for the anaesthesia vaporiser (a special closed recipient that contains the anaesthesia substance); not only can you not simply fill it the way it would be done on Earth, but even if you could, the anaesthesia liquid that becomes vapour cannot separate from the fluid from which it originates. It just cannot exit the vaporiser. Below is a small example of how liquids behave in space and what happens when a liquid exits a recipient: The same is true for another type of anaesthesia, called TIVA = Total Intra Venous Anaesthesia. This technique uses a dedicated syringe pump that pushes different anaesthesia substances through an intra venous line. It’s a useful technique both in terms of volume and energy expenditure, but again we face the same problems: how to fill the syringe without air bubbles and how to protect the electronics of the syringe pump (in fact a computer in all respects) from the deleterious influences of space radiation!

As you can see, space medicine is a very important topic and many people dream of its future use. Yet, we still have a long way to go! With the advent of intermediary space “stops” and the continuous development of new technologies, every challenge will be solved, sooner or later. Author: InnovaSpace TeamWorking towards a globally inclusive and diverse network of space professionals, researchers, entrepreneurs, students & enthusiasts - Space Without Borders  Time to catch-up with our colleague from the east, Chris Yuan, who very enthusiastically and capably established the Ursa Minor project in China, under the umbrella of the Planetary Expedition Commander Academy (PECA). It involves the development of new technologies and innovative training courses to encourage and inspire a future generation of space science researchers and astronauts. As previously reported in 2022, Chris and his students learned how to perform the Evetts-Russomano CPR technique underwater on a manikin while diving, as the water simulates the weightlessness that is present in microgravity. This practice now forms part of a larger course, the Ursa Minor Interstellar Expedition Program, giving the opportunity for 12- to 18-year-olds to participate in an underwater space science training camp.

Author: Tobias LeachMedical Student, University of Bristol | iBSc Physiology at King’s College London The first edition of the InnovaSpace Journal Club was dedicated to a prospective cohort study on jugular venous flow in astronauts aboard the ISS. From this study, the issue of jugular vein thrombus formation arose, which led to some fascinating discussion on how we could possibly manage and mitigate this novel risk to astronaut health. Therefore, I thought it appropriate to use the second edition of the InnovaSpace journal club to cover the issue of bleeding in space. Major Haemorrhage in space – How can it arise? How can it be managed? Should we worry about it? PAPER PRESENTED & DISCUSSED: We used a 2019 literature review which evaluated different haemostatic techniques in remote environments and proposed a major haemorrhage protocol for a Mars mission.

The article itself stressed that while the estimated risk for major haemorrhage on a Mars mission was not very high, there were still many possible causes for a big bleed such as trauma and high dose radiation. Additionally, the changes to circulatory physiology observed in microgravity may mean astronauts are less able to cope with even small amounts of blood loss. While the literature search itself left a lot to be desired as only 3 of the 27 papers were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the results were interesting. Author: Tomas DucaiBiology (microbiology/genetics) graduate, University of Vienna - Space (medicine) enthusiast "For most people, this is as close to being an astronaut, as you’ll ever get. It’s leaving planet Earth behind and entering an alien world.“ - Mary Frances Emmons - Editor-in-chief Scuba Diving, Sport Diver & The Undersea Journal magazines Mary Frances Emmons puts into words the indescribable atmosphere of scuba diving in which the boundaries become blurred between Earth and the sky above, or at least, to be more precise, the depths of space. It is this mixture of feelings that I want to experience – diving into the element of water, which is essential for life and where physical disabilities may not matter. I have been active in the world of space exploration for over a year now and am truly interested in promoting inclusion in the space sciences and analog space missions. I have been lucky enough to meet a lot of respected people and professionals doing amazing work with great passion in their respective fields, and they have also been keen to help and support me to realize my dreams A particular person who has shaped my dreams in concrete terms is Slovakia’s one and only aquanaut (underwater analog astronaut) and Chief Scientific Officer of the Hydronaut Project (unique underwater lab serving as a research facility for survival training in limited/extreme environments) - Miroslav Rozložník. Miro is an experienced scuba-dive instructor, who I met in Prague at an international analog astronaut community event. He offered to help me experience the unique underwater atmosphere through introducing me to the world of scuba-diving, a truly cherished offer that I gratefully accepted! At the same time, I knew that having a basic introduction to scuba diving may also enhance my chances of being selected as one of the three analog parastronauts for upcoming analog missions at the LunAres analog research station in Poland, especially if underwater mission experiments are being considered.

Author: Lukasz WilczynskiCo-founder European Space Foundation | Originator of the European Rover Challenge project. Experienced dot-connector and communication consultant specialising in technology and innovation.

This interview first featured on the European Space Foundation website

Author: Tobias Leach3rd Year Medical Student | University of Bristol | Passionate about space! Space provides boundless opportunities for human existence and innumerable threats to human health. The question is, are we yet prepared to deal with a catastrophic event, such as a cardiac arrest in space? Abstract

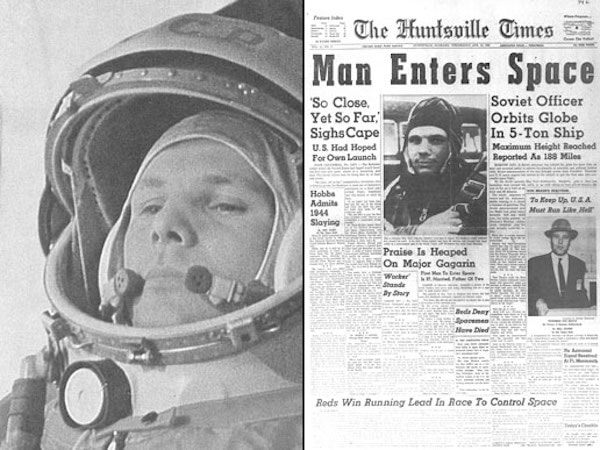

Introduction To gain an understanding of the current state of CPR in microgravity with a focus on chest compressions in the event of a sudden cardiac arrest onboard. Methods An Ovid Medline search was conducted: 17 articles were found; 12 were excluded; six additional articles were found in the references of the remaining five articles, bringing the total number of articles included to 11. These were then critically analysed. Results No CPR method currently reaches the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) guidelines. The Handstand (HS) method appears to be the strongest. Evetts-Russomano (ER) is the second strongest method. Automatic chest compression device (ACCD) performed consistently well. Conclusion CPR appears to be far more difficult in microgravity. Inconsistencies in research methodology do not help. The ER method should be used as a first contact method and the HS method should be used once the casualty is restrained. An ACCD should be considered as part of the medical equipment. Further research is needed, directly comparing all positions under the same conditions. Author: Paul Zilberman MDAnaesthesiologist, Israel MOTTO: I was born in 1960. As a child I was thrilled to witness the first man in space, as per stories, in those years a direct TV transmission was still a dream. And even if it had been possible, I was one year of age, so… But later on, I was able to see the launch of the Apollo missions and the common US-Soviet programs Soyuz- Apollo. As many other terrestrials I was thrilled to watch, both from distance and close up, those “white pencils” with the painting of “The United States of America” climbing faster and faster, leaving behind a huge ball of fire… Then the first carrying rocket segment detaching and falling back to Earth… I was amazed seeing how only after a short time those “people out there” were floating and smiling, waving their hands and telling us everything is ok. I was reading about the many experiments that were carried out during the flights, I was even able to look now and then at the flight path, little understanding what were the sinusoidal lines appearing on the huge Command Center screen, where so many people were sitting in front of the computers with the microphones and earpieces connected. I didn’t understand then, exactly, why so many people were dealing with so few in space.

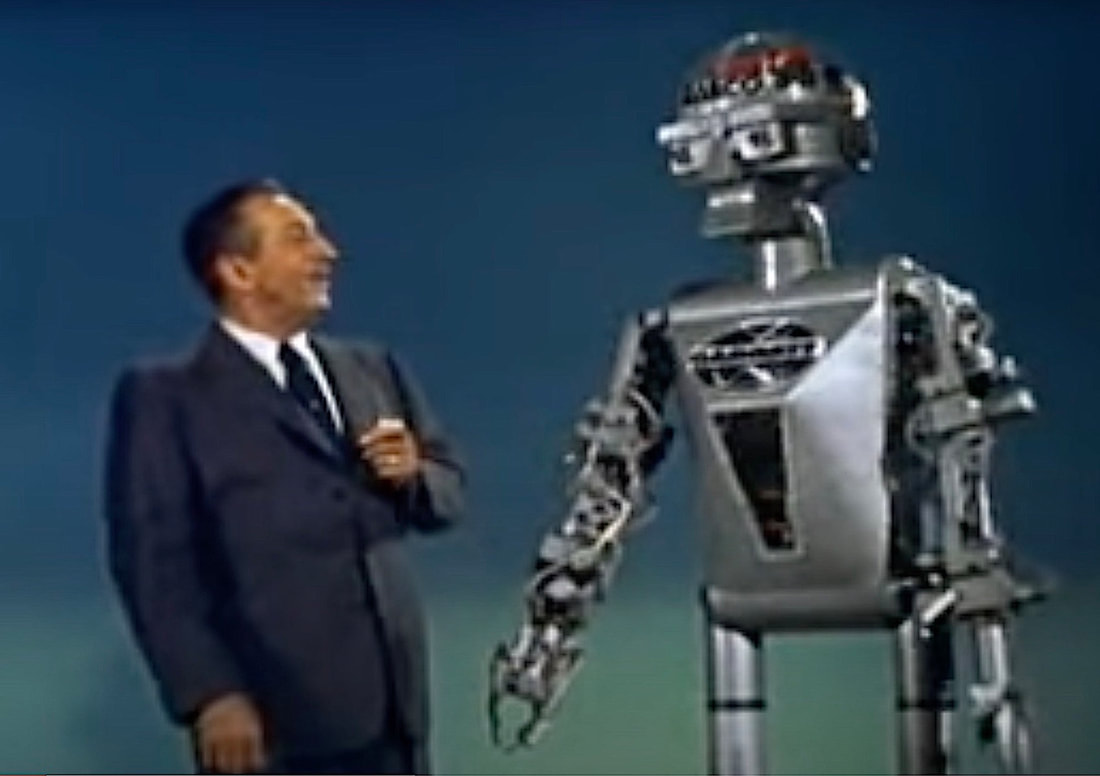

Well, time went on, Skylab appeared, then the ISS, the shuttles…wow…all in a lifetime. As time went on and understanding grew, on top of my medical school and, later on, anaesthesia residency, other questions arose: how do the astronauts eat, drink, wash, use the toilets? And many other daily mundane things we take for granted down here. Author: Rohan KrishnanUndergraduate, Bachelor of Science - Statistics & Healthcare Management | The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania In 1955, Walt Disney’s “Mars and Beyond” pondered human survival in extraterrestrial environments. The narrator envisions the colonisation of Mars as a feasible reality: a future where cities are encased in pressurised domes on the Red Planet to combat overpopulation and the depletion of natural resources on Earth. Today, NASA’s Artemis Mission plans to return astronauts to the moon by 2025, this time with an eye toward lunar colonization and human exploration of Mars. The boundaries that once constrained human space exploration are shattering, as technological advancements and ambitious government space programs bring plans for travel to Mars closer to reality. Beyond government space agencies, private companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX are innovating to create faster, more efficient aircraft and bring space travel to the masses through commercial flights. As astronauts inch toward deep space missions, understanding the general health risks of long-distance space travel, as well as the varied conditions between environments, is crucial. Missions to the International Space Station (ISS) and in low Earth orbit (LEO) have uncovered a variety of consequences for astronaut health, including bone loss, muscle atrophy, and a weakened immune system, amongst others. Radiation, microgravity, the distance from Earth, isolation, and the hostile environment inside spacecraft are the root causes behind the health issues that astronauts experience in space. Space exploration is vital for advancing life on Earth. Future missions across our solar system can help us understand the effects of microgravity and radiation on biological systems, locate valuable natural resources, and even combat overpopulation by exploring space colonisation. Given this need, ensuring the health of humans in space is the bedrock for further discovery. In this blog, I will describe the significant health challenges associated with with spending time in LEO and on long-distance spaceflight to the Moon and Mars. I have narrowed the focus to the following branches of medicine, to outline and contrast the particular health issues between LEO and long-distance spaceflight: cardiology, ophthalmology, and neurology. Many of the health concerns associated with time spent in LEO persist during long-distance space travel, but there are also challenges specific to the Moon and Mars stemming from their unique environmental characteristics, such as the presence of regolith and varying radiation levels. Understanding these general and environment-specific health concerns will inform planning as we venture deeper into space.

<

>

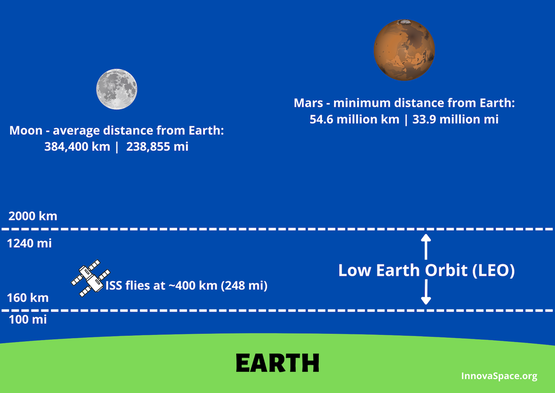

The vast majority of human spaceflight has occurred within low Earth orbit (LEO), with the notable exception of the Apollo program’s lunar missions. All manned space stations, including the ISS, are in LEO. As a result, for more than two decades, countless experiments have been conducted on the ISS to understand how astronauts’ health is impacted in LEO.

CardiologyResearchers studying the health of astronauts aboard the ISS have uncovered that long-term travel in LEO has notable effects on astronauts’ cardiovascular health. According to Dr. Thais Russomano, a leading expert on space medicine, the absence of Earth’s gravitational force in space causes bodily fluids and blood to shift from the legs and lower abdomen toward the upper torso and head. This phenomenon - referred to as ‘puffy-face and bird-legs syndrome’ - causes swelling in the face and head while reducing astronauts’ circulating blood volume and heart size. As less blood is pumped by the heart in microgravity, astronauts endure muscle loss in the heart, placing them at risk for cardiovascular deconditioning and cardiac myocyte atrophy.

Radiation is another significant concern impacting astronauts’ cardiovascular health. Aboard the ISS, radiation from galactic cosmic rays, solar cosmic rays, and particles from the Van Allen radiation belts are of primary concern. Astronauts are exposed to roughly 40-times more millisieverts of radiation compared to people on Earth. Exposure to space radiation over long-term missions increases astronauts’ risk for cancer and cardiovascular diseases, although effective shielding and radiation shelters aboard spacecraft have helped mitigate those risks. Cardiovascular issues resulting from microgravity and radiation exposure over long periods aboard the ISS can follow astronauts well after returning to Earth. Some studies have determined that astronauts’ arterial blood pressure decreased throughout space missions due to the loss in circulating blood volume, although there could be many causes behind this change. Similarly, the reduction in circulating blood volume can cause orthostatic intolerance - the inability to stand due to lightheadedness or fainting - once astronauts return to Earth. Although radiation exposure and microgravity cause cardiovascular problems in space, studies on astronaut mortality have concluded that astronauts are at a lower risk of death from cardiovascular diseases relative to the general population on Earth. OphthalmologyThe effects of bodily fluid shifting in microgravity extend beyond ‘puffy-face and bird-legs syndrome’, with consequences for the eyes. Following a six-month mission to the ISS in 2005, astronaut John Phillips’s perfect vision was found to have deteriorated due to spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS). SANS is formerly known as visual impairment and intracranial pressure (VIIP) syndrome, although the name was updated to reflect the uncertainty over whether increased intracranial pressure is the sole cause of the condition. One explanation is that SANS is caused by cerebrospinal fluid shifting toward the head, increasing intracranial pressure, particularly at eye level. The pressure causes the back of the eye to flatten, resulting in a hyperopic shift and blurred vision.

According to a report from the British Journal of Anaesthesia, a questionnaire of 300 astronauts found that 28% of short-duration mission astronauts and 60% of long-duration mission astronauts experienced degradation of visual acuity. A study of seven long-duration mission ISS astronauts and nine short-duration mission space shuttle astronauts found that the long-duration astronauts had significantly greater post-flight flattening when compared with the short-duration astronauts. Given the increased severity of SANS on long-duration missions, understanding causes and possible treatments are vital for exploration in and beyond LEO. NeurologyMicrogravity has notable effects on the nervous system, particularly due to the redistribution of bodily fluids in space. Neuroimaging scans show that astronauts’ brains have increased ventricular volumes following long-distance spaceflight. As fluids shift toward the upper torso and head during long-term exposure to microgravity, the volume of cerebrospinal fluid collected in the brain’s ventricles increases, resulting in ventricular expansion. Ventricular expansion could be a possible cause of SANS and may be linked to premature ageing of the brain. One study found that astronauts who spent 12 months in space displayed larger changes in ventricular volume than astronauts who spent 6 months in space, suggesting important implications for long-duration space missions. The microgravity-induced fluid shift is also associated with alterations to white matter in astronauts’ brains. A study from the journal Science Advances reports that cosmonauts displayed increased white matter in the cerebellum following long-duration spaceflight, with white matter volume returning to roughly pre-flight levels seven months after spaceflight. The cerebellum handles fine motor control, postural balance, and oculomotor control, and white matter changes associated with spaceflight may offer evidence for motor system neuroplasticity. Various studies are employing different techniques to evaluate white matter changes due to spaceflight, which could affect other neurological functions including visual and sensory processing. The health issues associated with LEO are also relevant for long-distance space travel. However, there are also environment-specific challenges unique to the Moon and Mars - such as high levels of space radiation and varying magnitudes of microgravity - that will be of primary concern to astronauts. Various studies simulate deep space environments to predict the effects of long-distance spaceflight on human health, informing mitigation strategies to keep astronauts safe.

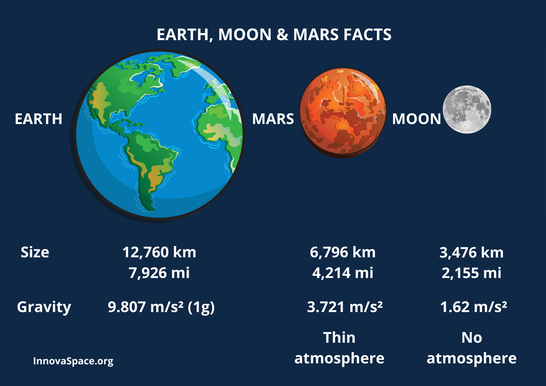

CardiologyIn deep space, the microgravity environment induces similar cardiovascular effects to what astronauts experience in LEO. Blood and bodily fluids shift toward the upper torso and head resulting in ‘puffy-face and bird-legs syndrome’, while the decreased cardiac workload can lead to cardiovascular deconditioning. However, relative to the gravitational force in LEO of approximately 0.95g, the Moon’s gravitational force is 0.16g while Mars’ gravitational force is 0.36g. It is unclear whether varied microgravity conditions will produce additional cardiovascular effects beyond those studied in LEO, however, fluid shifts and cardiovascular deconditioning remain significant concerns.

Radiation-induced cardiovascular disease is another major challenge with traveling to the Moon and Mars. Compared to missions in LEO, the space radiation environment beyond LEO exposes astronauts to higher dose rates of HZE particles, the high-energy heavy ions of galactic cosmic rays. HZE particles are highly penetrating and can cause secondary radiation when interacting with shielding in spacecraft or spacesuits. According to the journal Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, high doses of HZE particles over long-term deep space missions can lead to myocardial remodelling and fibrosis, potentially resulting in heart failure. While current shielding technology may protect astronauts in LEO, the power of HZE radiation makes more advanced shielding essential to protect astronauts in deep space. OphthalmologyConsidering the microgravity-induced fluid shifts that astronauts experience in deep space, SANS remains a primary concern for missions to the Moon and Mars. SANS is typically studied on long-duration missions, although astronauts have reported blurred vision after only two weeks aboard the ISS. A mission to Mars would take up to 20 months and would require astronauts to encounter multiple gravity fields. The long duration and complex gravity shifts associated with deep space missions could cause more challenging SANS-related ocular issues compared to those faced by astronauts in LEO. The concerns surrounding radiation beyond LEO extend to ocular health. Galactic cosmic radiation has been linked to the development of phosphenes and cataracts, while studies show that repetitive spaceflights and high-radiation-dose exposure increase the prevalence of both conditions among astronauts. Considering the high volume of HZE radiation that deep space astronauts will be exposed to, the development of phosphenes and cataracts is of major concern for their ocular health.

NeurologyPrevious studies have sought to evaluate the effects of space radiation on the human brain by delivering radiation doses to rodents over a few minutes. However, on missions to the Moon and Mars, powerful radiation will be gradually delivered to astronauts for the duration of the trip, ranging from weeks to years. A 2019 study from the journal eNeuro aims to more accurately simulate long-duration exposure by delivering low-level neutron radiation to mice for six months and evaluating the neurological implications. The study finds that exposure to cosmic rays impairs the brain function of the mice, affecting learning, memory, and mood. Lab tests reveal that following the neutron radiation, neurons are less responsive in the hippocampus - an area critical for the formation of memories and spatial navigation - and the medial prefrontal cortex - an area responsible for accessing preexisting memories, decision-making, and processing social information. Follow-up evaluations of the irradiated mice determine that neural circuitry damage may last for up to one year. Some researchers dispute the study’s approach, claiming that neutron radiation used in the experiment is not a viable surrogate for the galactic cosmic radiation that astronauts would encounter during deep space missions. Still, the eNeuro study offers a novel analogue to the gradual doses of powerful space radiation that astronauts would face on missions to the Moon and Mars, further emphasising the importance of effective shielding from cosmic rays. Researchers are also studying how microglia - the immune cells of the central nervous system - can be manipulated to prevent the development of cognitive deficits due to galactic cosmic ray exposure, a promising step toward protecting astronauts on deep space missions. ConclusionMotivated government leaders and entrepreneurs alike have expressed their commitment to bringing the human race beyond low Earth orbit. As breakthroughs in deep space research and aerospace technology bring this goal closer to realisation, concomitant advancements in space medicine must be made to safeguard astronauts’ health as they travel to and thrive in extraterrestrial environments. Before we can walk on Mars, our first step must be understanding and mitigating the health challenges that await us deeper into the final frontier. |

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed