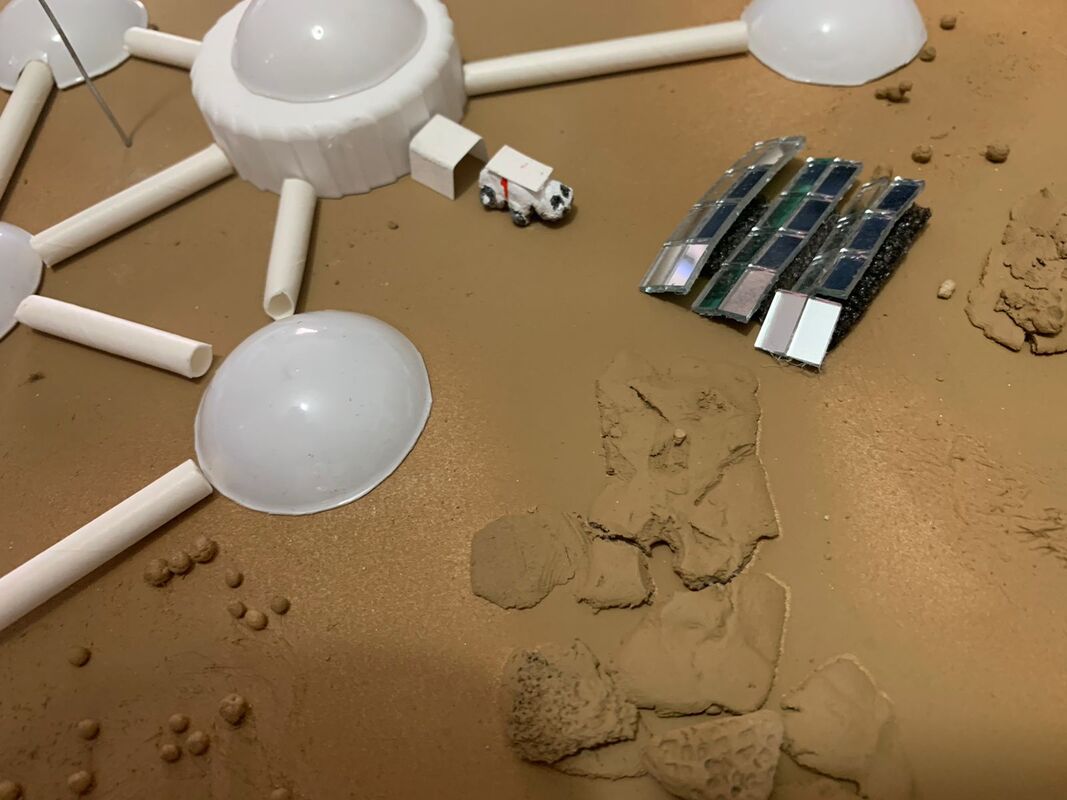

Author: Tomas DucaiBiology (microbiology/genetics) graduate, Master's student Molecular Biology, University of Vienna - & Space enthusiast!  Inclusion and Accessibility have been much discussed terms for years. Institutions are working on numerous fronts and in numerous areas of everyday life to implement them in society. My name is Tomas Ducai, I am 24 years old, an active wheelchair user and am confronted with the more or less successful effects of the implementation of the above terms on a daily basis. As a citizen of the city of Vienna, I enjoy the attitude to life in a city that has been described as the "most livable" in the world several times in a row - I can only confirm this from the position of an active wheelchair user. The fact that cities live and implement the credo of inclusion and accessibility may not sound entirely unusual - but the fact that these attributes also apply to organizations in the space sciences is quite extraordinary, innovative and gives physically disabled people with an interest in space, like me, hope to take part in projects in this area. I achieved this in March of this year when I took part in a simulated space mission in the so-called analog space habitat LunAres as the first wheelchair-using analog para-astronaut. Simulated space missions are missions in which life (or co-existence) with other crew members on an (analog) space station on another celestial body (usually the Moon or Mars) and all related processes (including simulated spacewalks) are simulated and trained. The focus of such a simulated space mission can be on simulating the environment of the celestial body as accurately as possible in detail or on simulating isolation (from the outside world - social and physical). In the Polish analog space habitat LunAres, the focus is mainly on the latter scenario. The aspects described at LunAres are expanded to include the attributes of inclusion and accessibility (of the habitat and all processes) mentioned at the beginning, and for good reason - not only the current project of the European Space Agency (ESA), which selected an astronaut with a physical disability for the first time as part of the last astronaut selection, should be mentioned here, but also the simulation of space missions with physically impaired people, since it is likely, especially on longer (real) space missions, that otherwise healthy crew members will be seriously injured and will have to continue their stay in space - thousands to millions of kilometers from Earth - with impairments. Dealing with such scenarios requires, as one can imagine, numerous simulations in advance, in which LunAres plays a pioneering role - it is so far the only analogue space habitat that carries out missions with physically impaired crew members. Our crew for the simulated, two-week Pegasus lunar mission was already diverse, apart from the fact that I was in a wheelchair. A total of six mission participants came from three continents, all with different academic backgrounds, with different tasks during the mission - the Commander and the Executive Officer were responsible for organizing the entire mission, had the final say on (critical) decisions and were in regular contact with the mission control center "on Earth". The Engineering Officer was the first point of contact for all technical questions about the habitat and was always on hand with "hands-on" access to help and advice. The Medical Officer looked after our medical well-being and monitored our most important medical parameters through measurements. The Communications and Outreach Officer was responsible for recording all impressions during the mission - a particularly valuable task in order to adequately present the activities during such a simulated space mission. I, the Biolab Officer, looked after the biology laboratory on the analogue space station and carried out experiments - I investigated the germination properties of spinach in conventional soil and "space soil" - ground meteorite powder - and was very pleased to see that the spinach itself germinated and began to grow in the "exotic" space substrate. I also supervised biological experiments by other crew members, while the Engineering Officer established new technical features on the "moon rover" Leo as part of our mission and generally took care of technical maintenance of our little helper during extra-vehicle missions. All this is just a small insight into the diverse activities during our simulated space mission on the Moon, which also included simulated spacewalks (which I was able to lead mostly from the moon base), meditation, and cooking traditional Polish pierogi (dumplings). Above all, however, were the attributes I mentioned - inclusion and accessibility - which were lived not only by us, all crew members, but also by the mission control center (the organizers and inventors of the analog space habitat LunAres) to emphasize that space is indeed for everyone! All images provided by Tomas Ducai.

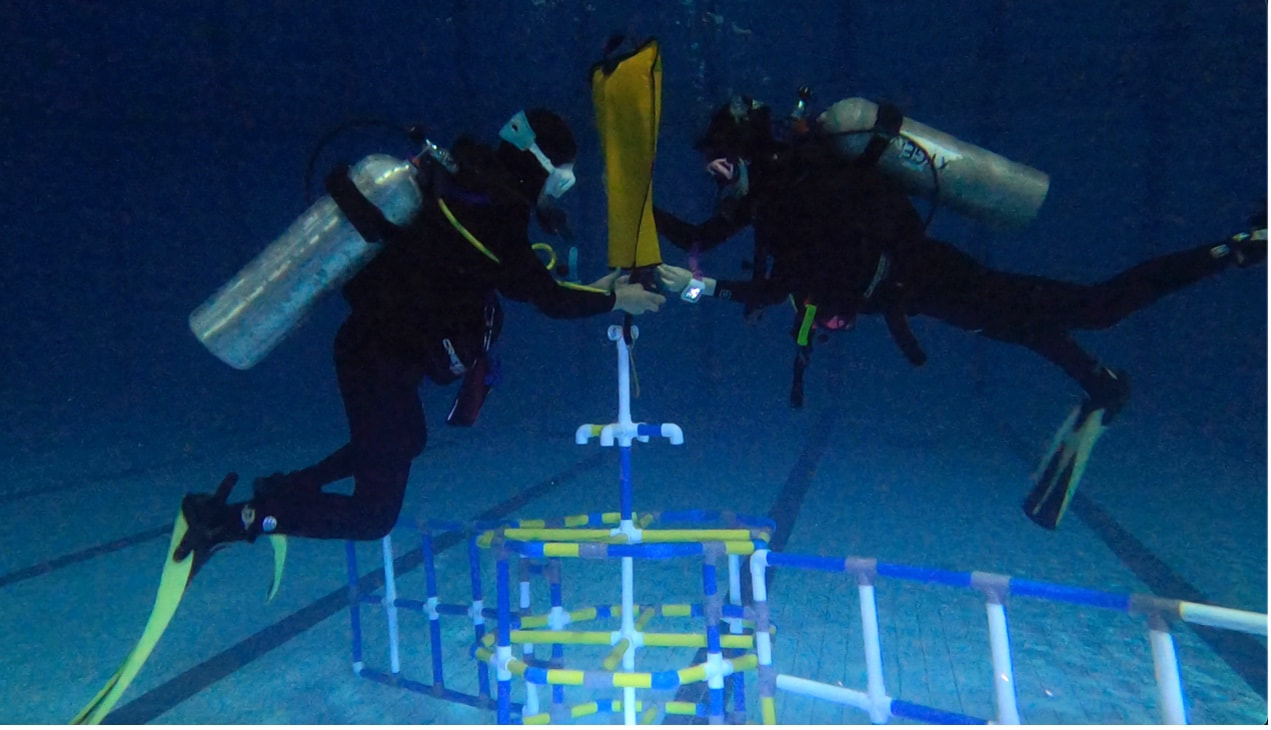

Author: InnovaSpace TeamWorking towards a globally inclusive and diverse network of space professionals, researchers, entrepreneurs, students & enthusiasts - Space Without Borders  Time to catch-up with our colleague from the east, Chris Yuan, who very enthusiastically and capably established the Ursa Minor project in China, under the umbrella of the Planetary Expedition Commander Academy (PECA). It involves the development of new technologies and innovative training courses to encourage and inspire a future generation of space science researchers and astronauts. As previously reported in 2022, Chris and his students learned how to perform the Evetts-Russomano CPR technique underwater on a manikin while diving, as the water simulates the weightlessness that is present in microgravity. This practice now forms part of a larger course, the Ursa Minor Interstellar Expedition Program, giving the opportunity for 12- to 18-year-olds to participate in an underwater space science training camp.

Author: Tomas DucaiBiology (microbiology/genetics) graduate, University of Vienna - Space (medicine) enthusiast "For most people, this is as close to being an astronaut, as you’ll ever get. It’s leaving planet Earth behind and entering an alien world.“ - Mary Frances Emmons - Editor-in-chief Scuba Diving, Sport Diver & The Undersea Journal magazines Mary Frances Emmons puts into words the indescribable atmosphere of scuba diving in which the boundaries become blurred between Earth and the sky above, or at least, to be more precise, the depths of space. It is this mixture of feelings that I want to experience – diving into the element of water, which is essential for life and where physical disabilities may not matter. I have been active in the world of space exploration for over a year now and am truly interested in promoting inclusion in the space sciences and analog space missions. I have been lucky enough to meet a lot of respected people and professionals doing amazing work with great passion in their respective fields, and they have also been keen to help and support me to realize my dreams A particular person who has shaped my dreams in concrete terms is Slovakia’s one and only aquanaut (underwater analog astronaut) and Chief Scientific Officer of the Hydronaut Project (unique underwater lab serving as a research facility for survival training in limited/extreme environments) - Miroslav Rozložník. Miro is an experienced scuba-dive instructor, who I met in Prague at an international analog astronaut community event. He offered to help me experience the unique underwater atmosphere through introducing me to the world of scuba-diving, a truly cherished offer that I gratefully accepted! At the same time, I knew that having a basic introduction to scuba diving may also enhance my chances of being selected as one of the three analog parastronauts for upcoming analog missions at the LunAres analog research station in Poland, especially if underwater mission experiments are being considered.

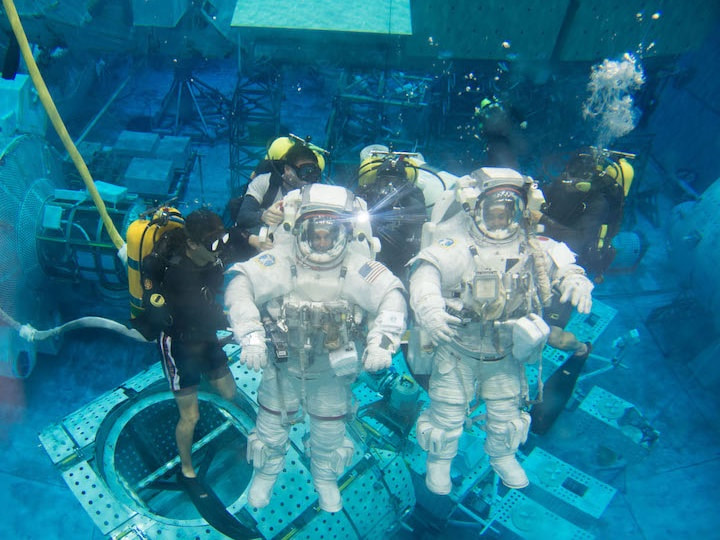

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a well-established part of basic life support (BLS), having saved countless lives since its first development in the 1960s. External chest compressions (ECCs), which form the main part of BLS, must be carried out until Advanced Life Support can begin. It is essential that ECCs are performed to the correct depth and frequency to guarantee effectiveness. The absence of gravity during spaceflight means that performing ECCs is more challenging. The likelihood of a dangerous cardiac event occurring during a space mission is remote, however, the possibility does exist. Nowadays, the selection process for space missions considers individuals at ages and with health standards that would have prohibited their selection in the past. With increased age, less stringent health requirements, longer duration missions and increased physical labour, due to a rise in orbital extravehicular activity, the risk of an acute life-threatening condition occurring in space has become of greater concern. The advent of space tourism may even enhance this possibility, with its popularity set to rise over the coming years as private companies test their new technology. Therefore, space scientists and physicians will have a greater responsibility to ensure space travellers, whether professional astronauts or space tourists, are adequately trained and familiarised with extraterrestrial BLS and CPR methods. Recently, work has been undertaken to develop methods of basic and advanced life support in microgravity and hypogravity, and several CPR techniques have been developed and tested. This blog presents one of these, the Evetts-Russomano MicroG CPR Method. Evetts-Russomano MicroG CPR Method In the Evetts-Russomano (ER) method, the rescuer can respond immediately, as it requires no additional CPR equipment/medication or the use of a restraint system. To assume the position, the rescuer places their left leg over the right shoulder of the patient and their right leg around the patient’s torso, allowing their ankles to be crossed approximately in the centre of the patient’s back; this is to provide stability and a solid platform against which to deliver force, without the patient being pushed away. From this position, chest compressions can be performed while still retaining easy access to perform ventilation. When adopting the ER CPR method, the rescuer must be situated in a manner that also allows sufficient space on the patient’s chest for the correct positioning of their hands to deliver the chest compressions. Extraterrestrial CPR simulation The main difference between extraterrestrial and terrestrial CPR is the strength of the gravitational field. In microgravity, patient and rescuer are both essentially weightless. When thinking about the technique of terrestrial CPR, with the rescuer accelerating their chest and upper body to generate a force to compress the patient’s chest, it is obvious that this cannot work in microgravity without significant aids. To this end, the ER CPR method has been developed using a ground-based microG simulation, during parabolic flights, and subsequently tested under-water! Video credits: Ground-based MicroG Simulation (land) = Space Researcher Lucas Rehnberg, MD (MicroG Center PUCRS, Brazil) Parabolic Flight MicroG Simulation (air)= Researchers = Thais Russomano, Simon Evetts, Lisa Evetts & João Castro (ESA 29th Parabolic Flight Campaign, Bordeaux, France) Underwater MicroG Simulation (water) = Sea King Dive Center, Chengdu, China - Instructor Gang Wei; Chinese Space First Responder & Space Researcher/Instructor Chris Yuan A project of InnovaSpace, PECA and Guangxi Diving Paradise Club, China Free Resource: Extraterrestrial CPR and Its Applications in Terrestrial Medicine

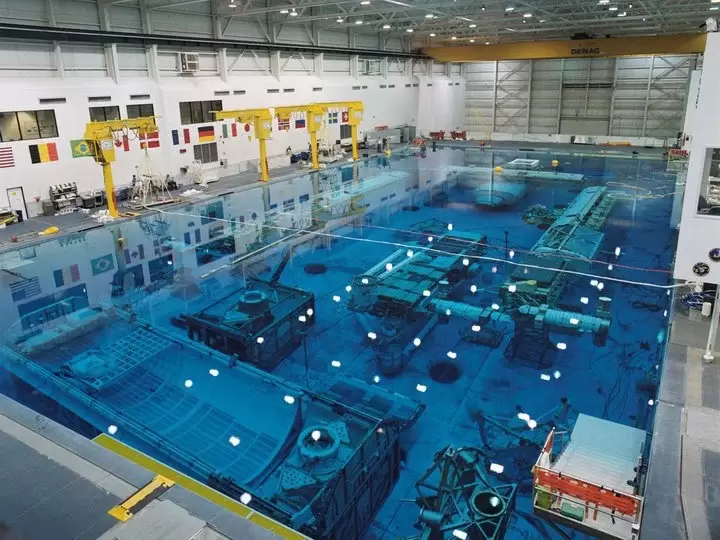

Authors: Thais Russomano, Lucas Rehnberg In book: Resuscitation Aspects, Ed: Theodoros Aslanidis Publisher: IntechOpen 2017 See Download Link at https://www.innovaspace.org/chapters.html Tiyoko HashimotoInstrutora de mergulho livre, mergulho autônomo e mergulhadora em formação no mergulho profissional raso LinkedIn Profile O mergulho faz parte de uma série de habilidades para quem busca a carreira astronáutica. Por quê? A água é cerca de 800 vezes mais densa que o ar, o que dificulta a movimentação subaquática, exigindo além de mais esforço, uma movimentação mais lenta para evitar fadiga que pode levar mergulhadores inexperientes a até abortar o mergulho. Além disso, a flutuabilidade neutra, ou seja, a capacidade de "boiar" na água permite que o praticante tenha a sensação semelhante à da microgravidade. Para fazer uso da flutuabilidade neutra como treinamento, as agências espaciais têm usado, ao longo dos anos, laboratórios subaquáticos como o NBL (Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory), localizado em Houston, no Texas, Estados Unidos e que faz parte do complexo da NASA. Segundo a NASA, possui 61,21 metros de comprimento, 30,90 de largura e 12,12 metros de profundidade e permite treinamentos como caminhadas espaciais, comunicação e segurança, além de permitir testes com equipamentos de vídeo e trajes espaciais. Na ESA (Agência Espacial Europeia), em Colônia, Alemanha, os astronautas são certificados no nível de mergulhadores de resgate. Esse conhecimento, segundo a ESA, permite melhor desempenho dos astronautas nas caminhadas espaciais e permite que previnam problemas e saibam lidar com emergências de modo adequado.

De acordo com a NASA, os astronautas utilizam nitrox (mistura de nitrogênio com uma porcentagem maior de oxigênio, também conhecido como ar enriquecido no mergulho) durante as sessões de treinamento no NBL. No mergulho dependente saturado não há perda de ar, nem se solta bolhas, como ocorre no mergulho recreativo. Todo o material exalado durante um mergulho saturado, que pode ir até 320 metros de profundidade, é recaptado, reciclado, para depois ser usado novamente na respiração. Isso ocorre porque o gás em questão, além do oxigênio, é o hélio, que tem um custo bastante elevado. Author: Chris YuanMember of the InnovaSpace Board of Advisors; CoFounder Planet Expedition Commander Academy (PECA), Explorers Club member, Space Dreamer... "Bang bang bang, bang bang," there was a knocking sound from the water. This is an 18-foot-deep pool in the diving hall of Nanning City Gymnasium in Guangxi. Two PECA (Planet Expedition Command Academy) trainees: Hannah and Selina, wearing scuba diving gear, are stitching together a satellite model underwater, which is designed with PVC pipes of different colours that are removable and can be spliced together. This training involves scuba divers simulating the role of space station EVA astronauts, capturing and repairing damaged satellites. The person under training must maintain neutral buoyancy during the whole process and retain sober analytical and hands-on ability under the conditions of maintaining air consumption, completing the assembly of the satellite model and bringing it out of the water. Hannah and Selina are mother and daughter, and Selina had just graduated from college and planned to have a gap year. The pair chose to participate in the 3-month PECA general training course. The scene just described was their training subject for PECA's second physical space, Ocean Planet: astronauts completing space missions in a simulated weightless state. They started from scratch and had already successfully completed the first physical space: Earth-Mountain Exploration, in which they completed a 10-day cross-country horseback trek on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and finally entered Tibet on horseback, after completing 235 kilometres of horseback riding. Finally they arrived in Guangxi, China and experienced a lot of confined water training, cave diving, to adapt to the exploration of the underwater world, and simulate future space travel. Selina had no previous experience with such a wide range of different exploration types, and when asked if she worried about whether she would be up to the challenges of the training, she said: "I chose to take this step, that is, I chose to face the unknown changes." The PECA curriculum has been seeking a path that connects the ordinary person at one end, with at the other end the coming age of great sailing for civilian space exploration (see also previous blog). Space exploration in the minds of most people is a national strategy, a game for a few people financially supported by the government, and super-rich people. Several of my friends have asked me a similar question, a pointed question:

"How do you think that space travel can become a majority movement in the future? How is their training program different from official astronauts?" Allow me to start with a story. Fifteen years ago, I rode a mountain bike alone from the Ger-mud area of Qinghai to Lhasa, Tibet, and then continued on until I reached the base camp of Mount Everest. This is the highest road in the world. My journey lasted 40 days, was 2200km and ended at the highest altitude of the Everest Base Camp. I later wrote a book "Through Your Eyes, See My Soul - 40 Days of Everest Ride". Some readers asked me the same question: "What is the most important prerequisite for a beginner who will ride the Qinghai-Tibet line? Sufficient money or physical reserves?" After thinking carefully, I replied: Neither of the two you mentioned are the most important, the most important thing is the ambition you have to go, it's the determination, it's the emotion. With that first push, money and other things follow." Think about it, it took only 66 years from the Wright brothers first successful test flight of their plane to the landing of a man on the Moon! Virtualmente em Marte - Minha Experiência como Astronauta Análogo na Estação Habitat Marte24/2/2022

Author: Maurício PontesOperational Safety & Crisis Manager, Pilot, Air Accident Investigator Encerramos após 11 dias (ou 11 sois, como denominamos o dia em Marte) a missão análoga (virtual) #96, celebrando quatro anos do estabelecimento da Estação Habitat Marte. Tive o privilégio de representar a InnovaSpace nessa experiência, que se revelou produtiva e instigante. As missões virtuais foram criadas em função da pandemia de COVID-19, como forma de manter a estação operando e fomentando o intercambio de experiências e informações sobre Marte e os desafios de se chegar ao planeta vermelho. A pioneira estrutura análoga, entretanto, é muito mais que isso. Localizado no agreste do Rio Grande do Norte, na cidade de Caiçara do Rio do Vento, o Habitat Marte é uma base física onde as condições inóspitas do terreno e algumas características relacionadas ao solo local propiciam um sítio ideal ao estabelecimento de missões com variados focos de pesquisa. Uma palavra que está sempre presente é sustentabilidade. Numa missão virtual, um clima de imersão e interação entre os cinco tripulantes é estimulado pela rotina de atividades como coleta de dados, apresentação de relatórios sobre o estado físico e mental e, ao longo dessa jornada, vai se criando uma atmosfera de imaginação coletiva acerca da presença no planeta vermelho, com o benefício da dinâmica das relações por interações remotas. Cada tripulante recebeu a incumbência de ser responsável por uma das estruturas críticas da estação (Estação Central e Centros de Engenharia, Saneamento, Saúde e Lançamento). Ao final, cada membro da missão fez uma apresentação sobre sua área de responsabilidade, encerrando a missão. Minha experiência pessoal na missão virtual foi ser o responsável pelo Centro de Lançamento (e retorno). Além de estar comprometido com a operacionalidade dessa área, incluí na rotina de relatórios o status “go & no go”, em função das condições técnicas ou meteorológicas, de modo a manter a estação ciente da viabilidade de um lançamento emergencial. A rotina de envio de relatórios é o grande gerador de valor para a simulação e vai ao encontro dos aspectos humanos: discutíamos situações que não decorreram de inputs do simulacro. Trocávamos informações e fotos, fomos inspirados a viver uma realidade paralela e a explorar nossa criatividade. Conversas sobre a missão e até pessoais foram constantes através de plataforma de mensagens e me mantiveram em constante “presença” naquela estação. Os dois relatórios de rotina diários (meteorologia e condições pessoais, como saúde, motivação, estado mental e satisfação com a missão e suas especificidades) eram enviados por um aplicativo e nos lembravam da nossa responsabilidade na jornada. Há potencial para ainda mais integração, pois nenhuma missão é igual à outra. Quem sabe, no futuro, um ambiente visual via aplicativo que possa até ser compartilhado com óculos de realidade virtual e celular não elevem ainda mais esses efeitos? Minha conclusão foi a de que estímulo ao pensamento, diversidade e o fator lúdico já são uma ferramenta de integração e compromisso com a missão de grande valor.

Parabéns aos tripulantes da Missão 96 e em especial ao Prof. Julio Rezende, pelo pioneirismo, determinação e criatividade. Próximo passo: a missão presencial! Author: Chris YuanCoFounder Planet Expedition Commander Academy, Explorers Club member, and Space Dreamer...

Author: Karin Brünnemann, PMP®Karin Brünnemann is PMI Slovakia’s first interplanetary project manager. Karin has more than 25 years of experience managing global strategic projects. She helps companies during phases of cultural change and digital transformation. Apart from being a PMP®, Karin is also a certified trainer for intercultural management. She is currently using her project management expertise in her work as a Flight Planner for the Austrian Space Forum’s AMADEE-20 analog Mars mission.  The Hydronaut project is an underwater habitat that started operations in 2020 and is currently the scene for analog space research. Dr. Miroslav Rozloznik, a Flight Planner for the Austrian Space Forum, conducted an underwater analog space mission in 2021 that was fully dedicated to science. The week-long mission, in which three analog astronauts participated, included a two-day underwater stay, and featured an EVA. Scientist-on-Board, Dr. Miroslav Rozloznik from Slovakia, conducted numerous experiments in the areas of physiology, microbiology, medicine, and space psychology. Dr. Rozloznik explained “Conducting underwater analog missions complements Moon or Mars simulations in land-based habitats. While we might not be able to test rovers, drones, or rock sampling procedures, the feeling in the underwater habitat is much more space-like. I felt very detached from Earth, even the support diver appeared like an alien, when he was looking into our porthole, dressed in his diving suit. The underwater habitat also offers the possibility to simulate more complex conditions like long periods of darkness, or variation in temperature and humidity. Furthermore, the ‘psychological safety net’ of being able to open the door and get help in case something happens, is not there. We can leave the habitat but will face several hours of decompression in cold water before we are back in a safe environment.” Part of the underwater experiments focused on the internal environment of the habitat, gathering data relating to air quality, temperature, humidity, and the microbiology of the habitat. Another area of research was dedicated to the medical and physiological well-being of the divers. Dr. Rozloznik tested novel diagnostic instruments, for example, a remote stethoscope that transmitted real-time heartbeat and breathing rates to a doctor located in the mission control center. Such equipment will be very useful for future space exploration and also has many applications for telemedicine on Earth. The crew also tested various biosensors, allowing for comparison and cross-link between physiological, neurophysiological, and psychological measurements. Author: Karin Brünnemann, PMP®Karin Brünnemann is PMI Slovakia’s first interplanetary project manager. Karin has more than 25 years of experience managing global strategic projects. She helps companies during phases of cultural change and digital transformation. Apart from being a PMP®, Karin is also a certified trainer for intercultural management. She is currently using her project management expertise in her work as a Flight Planner for the Austrian Space Forum’s AMADEE-20 analog Mars mission.

The AMADEE-20 analog Mars mission took place in Israel’s Negev desert during October 2021. Over the course of four weeks, an international crew of six analog astronauts conducted a number of experiments to study human behaviour and well-being; tested technical equipment, vehicles, and space suits; and deployed platforms and procedures in the areas of geoscience and life detection. A further aim of this Mars simulation was the development of a state-of-the-art Mission Support structure. I joined the AMADEE-20 team as a Flight Planner two years ago. In this role, I have been using my project management skills to help prepare and conduct scientific experiments as a member of the Mission Support team. Each experiment can be viewed as a subproject in itself and needs to be managed meticulously.  Sarah Feilmayr/OeWF (Austrian Space Forum)© Sarah Feilmayr/OeWF (Austrian Space Forum)© There are many similarities between my work as a Project Manager on Earth and my assignment as a Flight Planner for the analog Mars mission. To begin with, a Mars mission, whether simulated or real, is of course, a project. It is humanity’s most challenging, complex, risky, and expensive project. Like any other project, it can be divided into process groups. I started work on the AMADEE-20 Mars simulation during the planning process. One of my main tasks as a Flight Planner at this stage was to obtain a full and very detailed description of the experiments (subprojects) I had been assigned to. The output of these descriptions are documents comparable to a project charter. Since time “on Mars” is very limited during the mission, resources have to be assigned very carefully to the different experiments (subprojects) in order not to run into any resource conflicts. Furthermore, just like international projects on Earth, (analog) astronauts and Mission Support team members will experience cross-cultural differences and will be trained to handle them. One major difference between the projects I am normally working on, and this Mars simulation is the detail to which experiments (subprojects) have to be managed. Usually, I plan tasks for my project teams on a daily basis. For analog Mars projects, we have to plan tasks in time slots of 15 minutes. During a simulated and later real Mars mission, astronauts must wear space suits to protect themselves from the hostile environment on our neighbouring planet. As it takes a long time to put on a space suit and as they are very heavy and not comfortable to wear and work in, the time the astronauts can spend outside their habitat is very limited and therefore, very valuable and must be scheduled in great detail. Another difference is the high risk to human life and well-being, as well as to the safety of the usually very expensive equipment. Communication also poses a big challenge. The entire team has to almost learn a new language, consisting of many acronyms specific to space exploration. Simple Earth-words like “yes” and “no” are not used, since they can easily be misunderstood; we use “affirmative” and “negative” instead to express approval or disagreement.

Despite these differences, as a certified PMP® and trained analog Mars Mission Support team member, I am well prepared to take on this challenge. And as a Project Manager, I am of course, very much enjoying to expand my skills beyond Earth and to be part of creating the future of space travel and project management. If you want to learn more about this analog Mars mission, please visit https://oewf.org/en/portfolio/amadee-20/. If you want to learn more about project management for analog Mars missions, please contact me at [email protected] or https://www.linkedin.com/in/karinbrunnemann/. |

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed