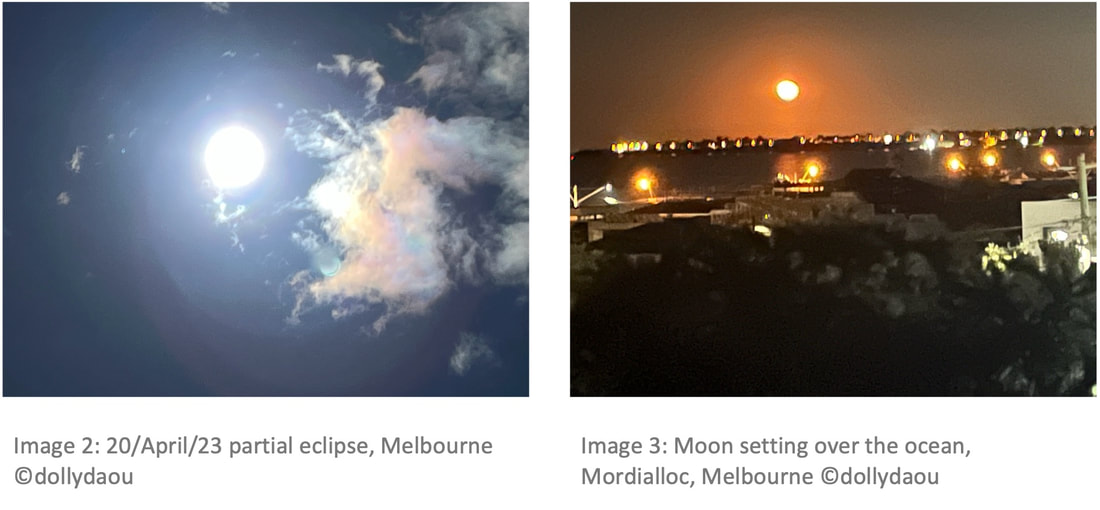

Author: Dr Dolly DaouInternational expert in design business innovation and strategies - International experience in design pedagogy/research, leading philanthropic associations and higher education programs and community projects in Australia, Asia, Europe and in the Middle East. (Visit: https://dollydaou.org/) I was inspired to write this blog in response to a post I saw on social media, where during an interview, one of the attendants asked: Who invented gravity and why do we need it? To the best of the attendant’s knowledge gravity was invented by Isaac Newton. These simple yet complex questions demonstrate the fragility of our knowledge and appreciation of gravity and reveal the inter-connection of these questions to each other. To be clear the reflections on gravity in this blog are not scientific, rather I am exploring the significance of gravity in our everyday as a design researcher. Throughout history the chain reaction of scientific explorations by Aristotle, to Bruno, Galileo, Kepler, Newton, much later Einstein, and then Hawking led to the discovery and adaptation of the theory of gravity. Although Newton could not explain the origin of gravity he did adapt Johannes Kepler’s law of gravitational theory, invented calculus and gave this force its name: gravity. Through this exploration, I open the scope of discussion for other disciplines to examine the power of this invisible force in our universe. Through interior and food design I demonstrate how gravity controls our daily lives from lifting an ordinary object to launching a rocket into space or designing a sustainable food system. We rely on gravitational forces of the planets during our interaction with our environment, especially in the food system gravity plays an integral part in the production, distribution, manufacturing and consumption of food. The images below of the Chinese mountains and Australian ocean show how the food system on our planet Earth is connected through a force that holds everything together called: gravity. If we understand gravity, we understand the story of creation of the universe, that grounds the human existence and conditions our neurology and physiology. We under-estimated the value of gravity in our everyday, which usually goes un-noticed. The complexity of questioning the origin and benefits of gravity lies in the simplicity of these questions; in the presumption that we should all know the answers. These questions are especially relevant now during our current exploration to the extra-terrestrial inhabitation with lower or zero-gravity environments, which reveal the significance of gravity as a un-negotiable part of our everyday life.

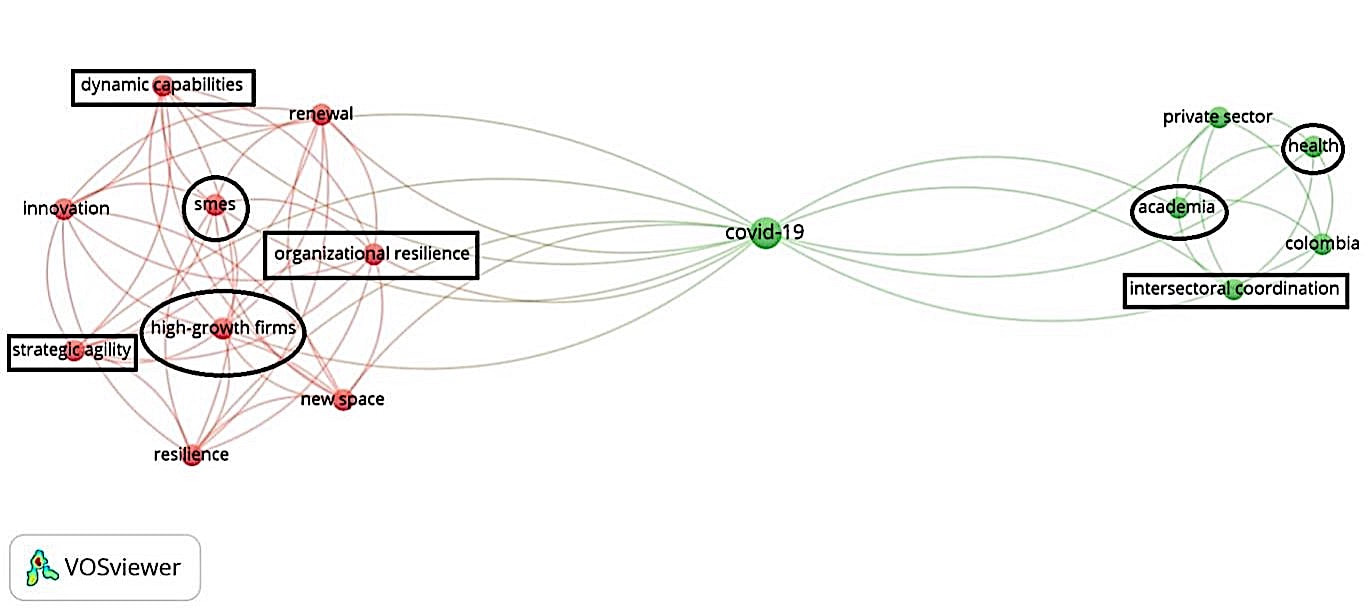

The term 'space sciences' is a conglomeration of almost all of the branches of science known to humanity today. Space fuels exploration and provides enormous opportunities for exploitation to meet societal needs. So much so that one finds the footprint of space technology in almost every aspect of daily life. For example, data received from earth observations help us to understand the global environmental factors and initiate ground-based measures to tackle them. Integrating data with fields like agriculture helped us develop 'Precision Agriculture'. Furthermore, space-driven initiatives drive international cooperation on issues related to humanity. Thus, it is pretty evident that any new crisis or breakthrough in almost any aspect of society will impact on the space industry. Such was the case when devastating waves of COVID-19 hit the world. Presented below is a bibliometric mindmap that gives us a visual aid to further our understanding of the true nature of the negative impact of the pandemic on the space industry. Figure: Impact of COVID-19 on the space industry and vice versa (Adopted with modifications from Palit S et al. - Space Industry and COVID-19: An Insight into Their Shared Relation) Note: Circles/ovals- Represent institutions affected by the COVID pandemic; Rectangles- Represent institutional values affected by the COVID pandemic It can be seen that the pandemic dealt a severe blow to institutions (such as SMEs, academia, the health sector) and their values (such as organisational resilience, etc.). However, as the saying goes, 'every cloud has a silver lining', and such was the case with COVID-19. Areas in which COVID-19 had positive implications include cases where:

Furthermore, astronauts onboard the International Space Station teach us some of the most valuable lessons. These include instances where the world applied containment measures to restrict the spread of pandemics, leading to the limited provision of healthcare resources. Here, the experiences gained with 3D printing during human spaceflights could help the healthcare industry to produce various tools (dental, medical, or surgical) and pharmaceutical products, and the list is endless.

Therefore, given the recent losses that we have suffered, it would be advisable to adopt space-based technologies as quickly as possible to help prevent the long-standing implications of COVID-19. However, this can only be done if we have collective support from government agencies worldwide. Author: Enric Garcia Torrents, MSc, PhD candidateMedical Anthropology Research Center, Universitat Rovira i Virgili The main role of a medical anthropologist is to study human health, the whole range of actual and potential care systems, and the ways in which biocultural adaptations emerge, succeed or fail from a transdisciplinary, multidimensional and ecological perspective. We contemplate the processes and situations from within and outside the limits of our own culture, and even our own civilisation, from a long-range evolutionary perspective to the minute details of small social networks analysis. We dive deep into the complexities and repeating patterns with a skill set and toolkit as sharp, in many cases, as that of a fully trained physician-scientist, being able to engage constructively in laboratory, fieldwork and clinical practice. “It is possible that the greatest contribution that anthropology can make will be to keep men's imaginations open, as they tend to let the predictable hardware coerce the form of the software.” Space medical anthropologists, on the other hand, are bound to take the whole field of medical anthropology one step further and even beyond, daring to question what it is to be a healthy human today, what it may mean to be so tomorrow, and indeed, what the near future might bring, depending on what we decide to do at this point in history. Most importantly, space medical anthropologists work on how to achieve this healthy state by skillfully setting the stage here and now, maximising humanity’s chance for a sustainable way onward to the stars. As for myself, nowadays I'm a scholar working as a doctoral candidate at a Medical Anthropology Research Center while undertaking medical studies (MD-PhD student-researcher, second and third year within the dual degree). I have previous academic background in neuroscience and smart systems, and currently a contract from the Spanish Ministry of Universities to undertake research on mental health and clinical decision making for choosing the best possible treatments for each individual, funded from a future professor’s training programme. My work on space medical anthropology is rather narrow, focusing almost exclusively on figuring out the best ways for people to withstand extreme experiences without losing mental acuity, exploring optimal solutions to boosting cognitive performance, resilience and overall wellbeing in situations of acute and profound distress.

Space psychology is an extremely significant area of study. Combining insights from all areas of the wider field (i.e., organizational, industrial, cognitive, psychiatry), it aims to optimise human behaviour and cognition in space.  Published January 1994 Published January 1994 In terms of its history, space psychology has received varying degrees of attention over time. Whilst its importance was acknowledged at the inception of NASA in 1958; in the early 1990s Dr Patricia Santy (a NASA flight surgeon and psychiatrist) illustrated the industry’s relative disregard for the area, claiming that the application of psychology to space was running 20-30 years behind most other areas of medicine. However, with ever-increasing pressure from academics (i.e., the Committee on Space Biology and Medicine), the establishment of continuously inhabited long-term research stations with multinational crews (i.e., with astronauts joining cosmonauts on Mir in 1993, and the first stay on the ISS in 2000), and a number of high-profile incidents, for example, the theorised termination of the Soviet Soyuz T14-Salyut 7 mission due to depression and the attempted murder by astronaunt Lisa Nowak, the relevance of psychological issues has become increasingly pertinent.  Research within the field is predominantly focused on ensuring selection/training programmes prepare astronauts for the psychological demands of space travel, developing effective inflight support strategies and helping individuals re-adapt following their return to Earth. Studies can be conducted both in-orbit, and in terrestrial simulators and space analogs (i.e., undersea vessels and polar outposts), which attempt to produce a degree of environmental realism, and have aided in identifying the consequences of the intrapsychic/interpersonal stressors that astronauts encounter, such as team conflict, impaired communication/”psychological closing”, social isolation, threat of disaster, high-stakes/demanding work, public scrutiny, microgravity, radiation exposure, immobility etc... Such research findings can then be applied to develop models of successful crew performance (i.e., in terms of gender composition, and types of goals) and produce effective intervention strategies, like enhancement medications and therapeutic software. For instance, optical computer recognition scanners have been developed by NASA to track astronaut facial expressions and assess potential changes in their mood, allowing for personalized intervention strategies (i.e. computerized CBT treatment). Notably, whilst much research focuses on studying/overcoming the negative aspects of space travel, a robust finding is the salutogenic “overview effect” (White, 1987), which refers to how viewing the Earth from space fosters a sense of appreciation/wonder, spirituality and unity amongst crew members. It is theorised by Yaden et al. (2016) that this emotional reaction is a result of the juxtaposition between the Earth’s features and the black backdrop of space, which emphasises the beauty, vitality, and fragility of Earth. With forecasted missions focusing on the potential for interplanetary (and eventually interstellar) travel, we need to prepare accordingly. Not only will these missions be much more protracted in terms of their distance/duration (with the longest period spent in space currently standing at 14 months, and a round trip to Mars predicted to take 2.5 years), they will also be subject to the pressure of larger, multinational crews, with no hope of evacuation, lack of protection from the Earth’s magnetic field, and distance-related communication delays (averaging 25 minutes to Mars/500 minutes to Neptune and back). Additionally, astronauts will not be able to observe the Earth and derive the aforementioned associated benefits of this experience; coined the ‘Earth-out-of-view phenomenon’ (Kanas, 2015; Kanas & Manzey, 2008), which may magnify potential feelings of homesickness and isolation. As such, we need to develop effective strategies to counteract these novel stressors, with researchers considering the benefit of fitting protective outer shields to isolated parts of spaceships (where astronauts spend the majority of their time) in order to mitigate against the effect of radiation from cosmic rays, email messages that conclude with suggested responses in order to reduce communication times, and virtual reality systems/on-board telescopes to minimise feelings of separation from Earth. Having discussed the historical development of space psychology, the scope of research conducted, and the forecasted future of the field, I hope I have impressed on you the significance of such an exciting area of study. Managing human behaviour in space is an interdisciplinary effort, and as the government monopoly on spaceflight diminishes (i.e., with the launch of commercial/private space ventures like SpaceX), and the number/complexity of missions increases, the importance of space psychology will become ever more apparent.

Blog written by Joaquim Ignácio S da Mota Neto, MD, MSc - Psychiatrist, Federal University of Pelotas, Brazil  Apparently, those weird green creatures who live on distant planets and who whizz across outer space, as seen in even weirder old sci-fi movies, are getting ready to be replaced by the very well known shape of human travellers! Among the many issues concerning human beings becoming extraterrestrials, either permanently or for short periods of time, are those concerning mental health. What happens to our minds in a situation like that? Is the human brain mouldable or adaptable enough to avoid an emotional crisis during such a challenging experience? Emotions and reactions to the environment are an inexorable part of human life - anxiety, fear, sadness, aggression, a wish to die, and so on. Most of these are quite usually seen as psychological or psychiatric features related to the common diagnosis of mental illnesses, such as panic disorder, major depression, psychosis or phobias. More than just feelings emerging from the latent, smouldering traits of someone's personality, they represent the way many portions of the cerebral cells and their connections are behaving in a particular period of time.  Depression is a disease that affects about 120 million people worldwide and is the leading cause of disability, according to World Health Organization. If we take this disorder as an example of a possible disruptive situation to be coped with during a space mission, we can understand the reasons why neuroscience is a very important medical field to be explored and to be put into perspective if trips like those to Mars are on the menu in the near future. Depression used to be described as the loss of the main appetites, i.e., a loss of appetite for work, food, sex, and for life itself. Perhaps more so than the feelings of sadness and hopelessness, the main real problems for depressed people are the lack of energy and decreased sense of interest or pleasure. There is also a huge impact on cognitive aspects, such as attention and memory, which reduces the ability of a person to accomplish minimal daily tasks, when mixed with insomnia, fatigue and psychomotor retardation. An affective disorder has biological and psychological triggers and it is obvious that while traveling or even living in space, the human body and all its organs, including the brain, must face troublesome phenomena, such as microgravity and cosmic radiation, not to mention the isolation and implicit fearful idea of a possible off-Earth death. Separately or together, and alongside genetic predisposition, these facts can represent the causes of mild or severe depression among crew members or civilians engaged in a space mission, besides eventually interfering in responses to treatment. "It is a little bit surreal to know that you are in your own little spaceship, and a few inches from you is instant death." NASA Astronaut Scott Kelly, 2016 Hundreds of experts and researchers have been trying to delineate all the important medical knowledge required in order to guarantee the success of space projects. It is also crucial to take into account that mental illnesses are able to jeopardise human lives and societies on any planet, regardless of whether that planet is blue or red.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed