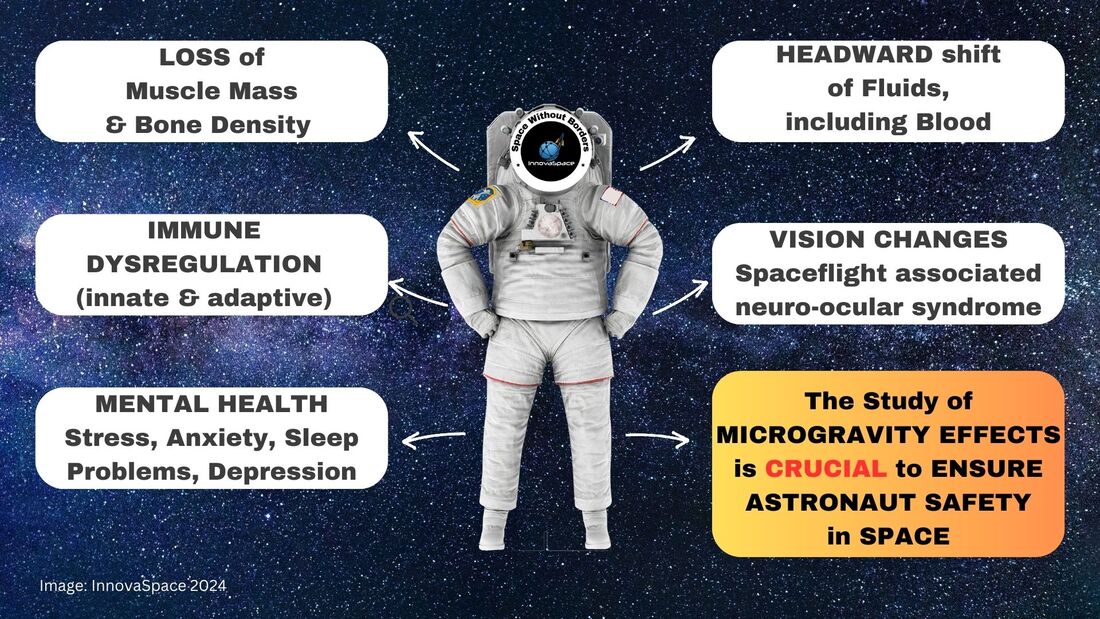

Author: Leonardo PilattiPhysiotherapist | Currently taking Master’s degree in Space Medicine Microgravity is a fascinating topic when it comes to the study of astronaut health. When humans are exposed to microgravity, the effects on their bodies can be quite significant. One of the first things to understand about microgravity is its effect on the musculoskeletal system. In the absence of gravity, astronauts experience a decrease in muscle mass and bone density. The lack of load-bearing activity in microgravity leads to muscle atrophy and bone loss. This can result in decreased strength and increased risk of fractures once astronauts return to Earth. Another area of concern in microgravity is cardiovascular health. On Earth, gravity helps to pump blood towards the lower extremities. In microgravity, this effect is greatly reduced, causing fluids and blood to shift towards the upper body. This can lead to a decrease in plasma volume. Astronauts often have to undergo intense exercise regimes during their space missions to counteract these effects. The immune system is also affected by microgravity. Studies have shown that the immune response of astronauts is suppressed during spaceflight. This can make them more vulnerable to infections and diseases. Researchers are still studying the exact mechanisms behind this phenomenon and are trying to find ways to boost the immune system during space missions. Microgravity also has an impact on the astronaut's vision. Some astronauts have reported changes in their vision, such as an increase in visual blurring and other visual disturbances. This condition, known as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), is still being studied to understand its underlying causes and potential long-term effects. In addition to physical health, microgravity can also impact an astronaut's mental well-being. The unique environment of space, with its isolation, confinement, and lack of natural daylight, can lead to psychological challenges such as mood swings, sleep disturbances, and increased stress. NASA and other space agencies provide mental health support and psychological training to help astronauts cope with these challenges. To mitigate the negative effects of microgravity on astronaut health, space agencies invest in various countermeasures. These include exercise programs, special diets, and even medications. Additionally, researchers are constantly studying new technologies and strategies to protect and enhance astronaut health during long-duration space missions.

In conclusion, microgravity has significant effects on astronaut health, impacting various systems in the body. The study of these effects is crucial to ensure the well-being and safety of astronauts during space missions. By understanding and addressing these challenges, we can continue to push the boundaries of space exploration while also safeguarding the health of those who venture into the final frontier. Author: Dr. Paul ZilbermanMedical Doctor, Anaesthetist, Hadassah Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel

Space is very different, in many aspects. This post does not attempt to address the many changes the human body experiences in space, such as volume modifications in body compartments, fluid shifts, structural configuration in receptor* morphology and, as a consequence, possible variations in pharmacology response, etc. * For the lay reader, a receptor is a special structure on the surface of a cell, for example, that functions as a "receiving point" on which a chemical substance acts in a unique way (like a key – lock mechanism) and a specific reaction is generated (like a muscle contraction) or inhibited (like a cork closing a bottle and blocking the passage of a fluid). These complex structural changes modify many biological reactions, as well as the body’s response to medications. Rather, this post presents some of the technical challenges that an anaesthesiologist may encounter in space. Confined space. On Earth gravity keeps everyone’s feet on the ground. Different pieces of equipment can be repositioned depending on the procedure, machinery can be brought in as needed (XRay scans in orthopaedics, for instance), electric cables can be switched to other convenient wall sockets etc. In a fixed volume space capsule, you don’t have all these possibilities. Everything is measured for maximum volume efficiency. Taking into consideration that anything can and will float if not properly anchored, we can imagine what an “anaesthesia dance” could happen! What equipment? On Earth an anaesthesia workstation is always present in the OR. Depending on its complexity its volume can vary between a medium size fridge to a large double-doored one, just put on its side. You don’t have this amount of deposit in a space cabin, but let’s suppose for one moment that you do - you then need an Anaesthesia Gas Scavenging System (AGSS), which removes the anaesthesia gases that have leaked out or at the end of the procedure. On Earth, these gases are expelled into the atmosphere (there is a lot to talk about this and the greenhouse effects too) and the air currents around any medical facility carry them away. In space you don’t have this. Any gas must be expelled using energy, an active process. Otherwise, the whole cabin will become a big anaesthesia machine with all crew members affected. And, speaking of energy, an anaesthesia workstation is also powered by electricity, which is a limited resource in space, depending on the surface of the solar (or light in general) panels. This energy must be stored and used for other life maintenance systems as well, of which a critical example is the Sabatier reactor that provides oxygen. Regional anaesthesia The simplicity and portability of the necessary equipment makes this type of anesthesia attractive. For peripheral neural blocks all you need is a simple ultrasound machine and dedicated needles. The potential drawbacks are that the technique/s need to be taught on Earth but their “transposition” to space is a bit problematic. If the spinal/epidural anaesthesia is relatively simple to learn, the USG (ultrasound guided) blocks are more challenging. Furthermore, the bodily fluid shift due to the lack of gravity causes many tissues to change their tridimensional appearance, leading to increased difficulty in performing the block.

The cardiovascular responses that accompany spinal/epidural anaesthesia on Earth, in terms of heart rate and blood pressure, are different in space. There may be a lack of reactivity so a certain reduction in blood pressure, for example, might not be compensated. We need to remember that the hostile environment in space, especially radiation, affects not only the human body, but also many sensitive electronic components of medical equipment, leading to possible dysfunction. Monitors can potentially de-calibrate and all the information you receive may become inaccurate. Fluids Preparing and administering a fluid on Earth is routine, however, the lack of gravitation in space poses other challenges: air and fluids do not mix. It is called “lack of buoyancy”. Unless we use special equipment to separate fluids from air nothing can be delivered to the patient. This statement is true also for the anaesthesia vaporiser (a special closed recipient that contains the anaesthesia substance); not only can you not simply fill it the way it would be done on Earth, but even if you could, the anaesthesia liquid that becomes vapour cannot separate from the fluid from which it originates. It just cannot exit the vaporiser. Below is a small example of how liquids behave in space and what happens when a liquid exits a recipient: The same is true for another type of anaesthesia, called TIVA = Total Intra Venous Anaesthesia. This technique uses a dedicated syringe pump that pushes different anaesthesia substances through an intra venous line. It’s a useful technique both in terms of volume and energy expenditure, but again we face the same problems: how to fill the syringe without air bubbles and how to protect the electronics of the syringe pump (in fact a computer in all respects) from the deleterious influences of space radiation!

As you can see, space medicine is a very important topic and many people dream of its future use. Yet, we still have a long way to go! With the advent of intermediary space “stops” and the continuous development of new technologies, every challenge will be solved, sooner or later. Author: Tobias LeachMedical Student, University of Bristol | iBSc Physiology at King’s College London The first edition of the InnovaSpace Journal Club was dedicated to a prospective cohort study on jugular venous flow in astronauts aboard the ISS. From this study, the issue of jugular vein thrombus formation arose, which led to some fascinating discussion on how we could possibly manage and mitigate this novel risk to astronaut health. Therefore, I thought it appropriate to use the second edition of the InnovaSpace journal club to cover the issue of bleeding in space. Major Haemorrhage in space – How can it arise? How can it be managed? Should we worry about it? PAPER PRESENTED & DISCUSSED: We used a 2019 literature review which evaluated different haemostatic techniques in remote environments and proposed a major haemorrhage protocol for a Mars mission.

The article itself stressed that while the estimated risk for major haemorrhage on a Mars mission was not very high, there were still many possible causes for a big bleed such as trauma and high dose radiation. Additionally, the changes to circulatory physiology observed in microgravity may mean astronauts are less able to cope with even small amounts of blood loss. While the literature search itself left a lot to be desired as only 3 of the 27 papers were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the results were interesting. Author: Dr. Paul ZilbermanMedical Doctor, Anaesthetist, Hadassah Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel This article addresses the notion of buoyancy and why drinking beer in space (the ISS usually orbits in the thermosphere), or any carbonated drink for that matter, does not produce the known tingling sensation we can feel in our noses here on Earth. So let’s first briefly consider what is buoyancy? In simple terms, whenever an object is put into a fluid there are several forces that act upon it. The liquid exerts a force from the bottom upwards that tries to push that object up. Then there is the liquid force itself, let’s call it weight, that pushes an object downwards. However, because the liquid pressure increases the deeper you go down into the fluid, there will always be an upwards force bigger than the downward force. This can be explained by looking at the formula for hydrostatic pressure: Hydrostatic pressure = pgh In this formula, p is the density of the liquid, g is the gravitational force (9.81 m/s2) and h is the height of the fluid column measured from the surface. Keeping all the other parameters of the formula constant, the "h" at the bottom of a submerged object will be higher than the one at its top. But we also have here another component: the "g". Well, there is practically no "g" in space, unless we artificially produce it. So, in this case, all the objects inserted or included into a fluid will just stay there. Of course, there are many other factors that play a role here, for example the superficial tension of the fluids etc., however, for the sake of simplicity I am considering here only the buoyancy. So, nothing happens with the CO2 bubbles inside the fluid because they are no lighter than the fluid that surrounds them, perhaps looking something like in this photo: This not mixing between the fluid and gases within creates a hard enough life for anyone who would like to enjoy a beer in space (hypothetically, at least as alcohol consumption is not permitted on the ISS), but let's also not forget the cabin temperature of roughly 20 degrees Celsius, which is way too high to enjoy an ice cold beer. If you want to cool it a bit forget leaving it outside too - just take a look at what the temperatures are "outside", unless of course you want to lick your beer like an ice-cream!

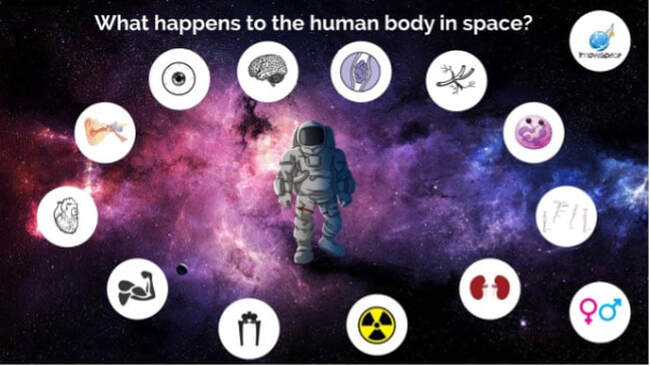

Author: Lucas RehnbergNHS Doctor - Anaesthetics & Intensive Care | MSc Space Physiology & Health  My name is Lucas, I am a doctor in the UK working in anaesthetics (or Anaesthesiology for any American readers) and intensive care medicine. I have had an interest in space medicine for over 10 years now, inspired by none other than Prof Thais Russomano who has mentored me over the years and still does. My Master’s dissertation (back in 2009) focused on CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) methods in microgravity, with my continued research interest surrounding critical care in space. I am careful to say that I am a doctor with an interest in space medicine and physiology, as opposed to a ‘Space Doctor’ – as there are many individuals out there who have committed many more years than I have to this field and are vastly more experienced than I am! A club I aspire to join one day. The idea of this blog, or series of blogs, is to look at some of the latest research in space physiology and space medicine, then consider how this will play out clinically. With a particular focus on critical care and potentially worst-case scenarios when in space (or microgravity environment). Something all doctors will have done in their careers; we are equipped with the skills to critically appraise papers and then ask if they are clinically relevant, or how will it change current practice. Over the last 60 (ish) years of human space flight, there is lots of evidence to show that there are many risks when the human body has prolonged exposure to microgravity, which can affect most body systems – eyes, brain, neuro-vestibular, psychological, heart, muscle, bone, kidneys, immune system, vasculature, clotting and even some that we haven’t fully figured out yet. But then what needs to be done is to tease out how clinically relevant are these from the research, how could that potentially play out if you were the doctor in space, then how to mitigate that risk and potentially treat it.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed