|

Space psychology is an extremely significant area of study. Combining insights from all areas of the wider field (i.e., organizational, industrial, cognitive, psychiatry), it aims to optimise human behaviour and cognition in space.  Published January 1994 Published January 1994 In terms of its history, space psychology has received varying degrees of attention over time. Whilst its importance was acknowledged at the inception of NASA in 1958; in the early 1990s Dr Patricia Santy (a NASA flight surgeon and psychiatrist) illustrated the industry’s relative disregard for the area, claiming that the application of psychology to space was running 20-30 years behind most other areas of medicine. However, with ever-increasing pressure from academics (i.e., the Committee on Space Biology and Medicine), the establishment of continuously inhabited long-term research stations with multinational crews (i.e., with astronauts joining cosmonauts on Mir in 1993, and the first stay on the ISS in 2000), and a number of high-profile incidents, for example, the theorised termination of the Soviet Soyuz T14-Salyut 7 mission due to depression and the attempted murder by astronaunt Lisa Nowak, the relevance of psychological issues has become increasingly pertinent.  Research within the field is predominantly focused on ensuring selection/training programmes prepare astronauts for the psychological demands of space travel, developing effective inflight support strategies and helping individuals re-adapt following their return to Earth. Studies can be conducted both in-orbit, and in terrestrial simulators and space analogs (i.e., undersea vessels and polar outposts), which attempt to produce a degree of environmental realism, and have aided in identifying the consequences of the intrapsychic/interpersonal stressors that astronauts encounter, such as team conflict, impaired communication/”psychological closing”, social isolation, threat of disaster, high-stakes/demanding work, public scrutiny, microgravity, radiation exposure, immobility etc... Such research findings can then be applied to develop models of successful crew performance (i.e., in terms of gender composition, and types of goals) and produce effective intervention strategies, like enhancement medications and therapeutic software. For instance, optical computer recognition scanners have been developed by NASA to track astronaut facial expressions and assess potential changes in their mood, allowing for personalized intervention strategies (i.e. computerized CBT treatment). Notably, whilst much research focuses on studying/overcoming the negative aspects of space travel, a robust finding is the salutogenic “overview effect” (White, 1987), which refers to how viewing the Earth from space fosters a sense of appreciation/wonder, spirituality and unity amongst crew members. It is theorised by Yaden et al. (2016) that this emotional reaction is a result of the juxtaposition between the Earth’s features and the black backdrop of space, which emphasises the beauty, vitality, and fragility of Earth. With forecasted missions focusing on the potential for interplanetary (and eventually interstellar) travel, we need to prepare accordingly. Not only will these missions be much more protracted in terms of their distance/duration (with the longest period spent in space currently standing at 14 months, and a round trip to Mars predicted to take 2.5 years), they will also be subject to the pressure of larger, multinational crews, with no hope of evacuation, lack of protection from the Earth’s magnetic field, and distance-related communication delays (averaging 25 minutes to Mars/500 minutes to Neptune and back). Additionally, astronauts will not be able to observe the Earth and derive the aforementioned associated benefits of this experience; coined the ‘Earth-out-of-view phenomenon’ (Kanas, 2015; Kanas & Manzey, 2008), which may magnify potential feelings of homesickness and isolation. As such, we need to develop effective strategies to counteract these novel stressors, with researchers considering the benefit of fitting protective outer shields to isolated parts of spaceships (where astronauts spend the majority of their time) in order to mitigate against the effect of radiation from cosmic rays, email messages that conclude with suggested responses in order to reduce communication times, and virtual reality systems/on-board telescopes to minimise feelings of separation from Earth. Having discussed the historical development of space psychology, the scope of research conducted, and the forecasted future of the field, I hope I have impressed on you the significance of such an exciting area of study. Managing human behaviour in space is an interdisciplinary effort, and as the government monopoly on spaceflight diminishes (i.e., with the launch of commercial/private space ventures like SpaceX), and the number/complexity of missions increases, the importance of space psychology will become ever more apparent.

ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen delivers the last part of his 'Let's Talk Science' blogs, written during his year at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica But there is more to the ESA lab, and I have saved the best for last. So, now that you are probably overloaded with theories and facts, let’s talk about something very different. Let’s talk about sex! And before we continue, you have to promise me to turn on another song, to end this blog with some appropriate groove.

But maybe there is more to it than it seems, and what Cherry-Garrard says is not necessarily easy to do. We are human, after all. Sexuality is one of our core features, vital for our existence, and for many it is a fundamental source of pleasure, intimacy, bonding, and social relations. Researchers have shown how sexual deprivation can lead to frustration, anger and even depression, and also seen from a group perspective anecdotal accounts have shown that sexual desire and related feelings of jealousy and competition can lead to adaptation problems in extreme environments. Including Concordia! But the problem with sex it that we don’t easily talk about it. Perhaps it is so close to our core that opening up about it can make us feel vulnerable. A sensitive topic, and while researchers are currently busy figuring out how to compose future space crews in terms of culture, personality and gender, data about sexual behaviour and its effects on team dynamics in extreme environments is basically non-existent! How do we cope? How, why, and when do we suffer? Recent political debates and scandals of sexual harassment have already highlighted the importance of having a work environment free of sexual hostility, and if you ask me, it would be irresponsible to send humans on a multi-billion dollar long-duration mission to Mars without being able to answer these questions! As such, the project SWICE (‘sexual well-being and sexual security in isolated, confined and extreme environments’), for the first time in spaceflight research history, is breaking the taboo. As the first study of its kind, it aims to gather basic information about human sexuality while living in isolation and confinement, and it does so by making us in Concordia talk:

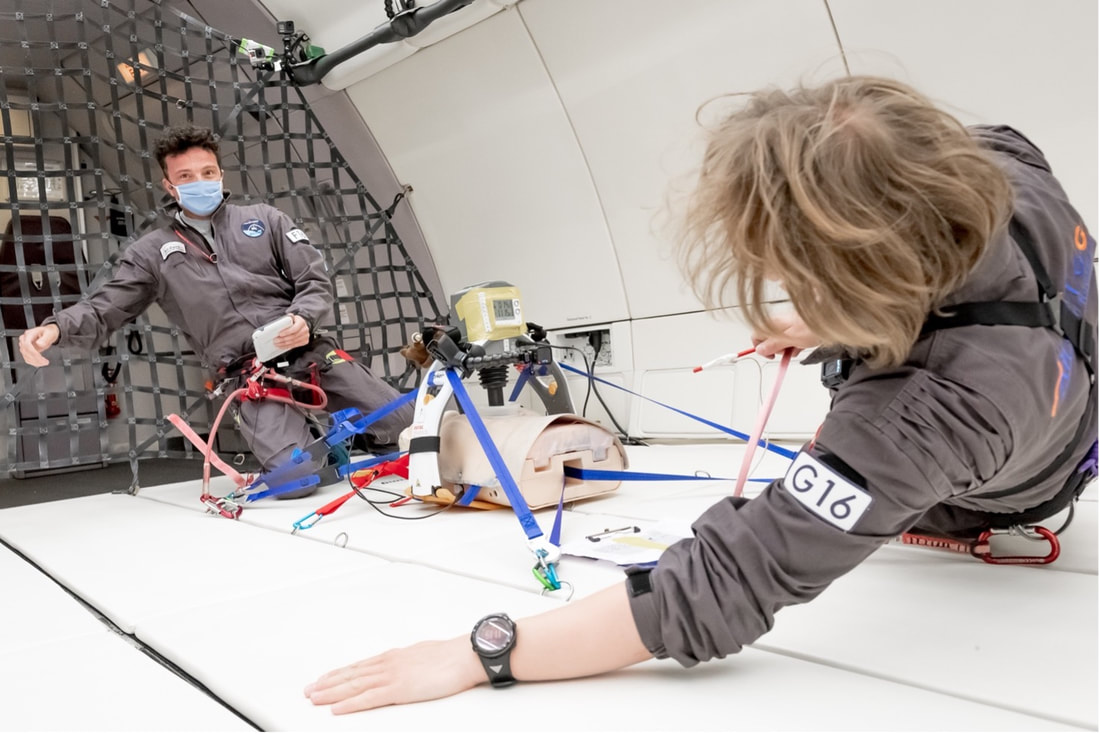

‘How often does another Concordia inhabitant asks me for sexual favours?’ (we better forget the jokes at the dinner table…), ‘How often does another Concordia inhabitant produces sexually explicit graffiti for display at Concordia?’ (we better forget the sexually explicit Play-Doh creations we made with the whole crew last month…), ‘How enjoyable is your sexual life right now?’, ‘How often do you masturbate?’, ‘How often do you experience an orgasm?’ (Damn, you want to know everything!).  Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons If someone asked you – “what do you want to do when you become an adult?" – what would your response be? Now, imagine me as a 14-year-old student at an art school, and one day going to a Red Cross course and recognizing that you love the idea of the First Rescue and Emergency services. My first answer was always – Astronaut! But… what should I do now? Astronaut or Doctor ...? Solution? Helicopter flight physician! But how can I do this thing…is it possible? Yes, it is! I first studied medicine and became an anesthetist and intensivist. And so it was… once I graduated and then specialized in anesthesia, I began to frequent the world of Helicopter Rescue. A fantastic job that combines flight, wonderful landscapes (the Dolomites ...) and the human factor. A lot of different situations every day and in different places. The helicopter flight physician is responsible for providing casualties with emergency medical assistance at the accident site, as well as attending to patients during primary and secondary missions. The scope of activities also involves recovering patients from topographically difficult terrain by means of a rescue hoist. This applies exactly from the time the patient is put into your care until you hand them over to the medical staff responsible at the destination hospital.  LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions I remember one early afternoon in September 2013, the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) Dispatching Centre of Treviso, Italy received a call from a person who told the operator that her cousin, a 53-year-old man with a previous history of inferior myocardial infarction, had suddenly fallen down while walking at home. While dispatching the nearest ambulance, the dispatcher provided CPR pre-arrival instructions to the caller, according to standard protocols. An EMS helicopter, staffed by an emergency physician (namely, me!) and a nurse, was dispatched to the scene. The first emergency unit, staffed by a nurse and an emergency technician, reached the patient within 10 minutes of the call and found the woman performing chest compressions as instructed by the dispatching center operator. My team in the helicopter reached the patient 10 minutes after the first unit started ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support). The cardiac rhythm was a persistent ventricular fibrillation and the decision was made to apply a LUCAS-3 chest compressions device to the patient, who was then transported directly to the hospital and catheterization laboratory. Selective percutaneous coronary angiography was performed with ongoing continuous mechanical chest compressions. Coronary angioplasty was performed on two coronary arteries. Five days after resuscitation, the patient was extubated and was alert and oriented. After 16 days he was discharged from the Intensive Care Unit and transferred to a post-intensive care unit. The patient survived without any neurological damage despite prolonged resuscitation and a call-to-ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) interval of nearly 2 hours. The immediate beginning of chest compressions by the caller and uninterrupted CPR by medical teams preserved the brain from ischemic damage. The mechanical chest compression device permitted safe and effective CPR during helicopter transportation directly to the catheterization laboratory, which permitted the removal of the coronary artery occlusions, which were preventing the ROSC. This is why I think this is an amazing job… A little about the author: Alessandro Forti As well as being a certified specialist in Cardiac-Anaesthetics, Intensive Care Medicine and Aerospace Medicine, currently working as an intensivist, cardiac-anesthesiologist and HEMS doctor in northern Italy, Alessandro has a passion for space clinical medicine, which began in 2012 following a post-graduate course in Space Medicine at the San Donato Milanese University. He has been involved in space medical research as a COSPAR (Committee on Space Research) collaborator and acted as a reviewer of many scientific articles for the journal Advances in Space Research (Elsevier). He was also Coordinator of the HEMS base in Pieve di Cadore-Italy from 2018-2020. Alessandro is Principal Investigator for the research Mechanical Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Simulated Microgravity and Hypergravity Conditions: a manikin study, which took place during the 4th. parabolic flight campaign in Dübendorf (CH) in June 2020, in collaboration with the SkyLab Foundation, CNES and DLR. His main areas of interest are space clinical medicine, CPR in different environments (mountain, avalanche victims, hypothermia, hyper and microgravity), ongoing CPR with ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) neuroprotection and neuromonitoring during DHCA (Deep Hypothermia Cardiac Arrest) in Cardiac Surgery.

We continue to follow along with the wonderful experience of ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen during his year spent at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Fortunately it is not all body fluids (and solids) in the ESA lab. Other projects are more interested in the psychological adaptation to space-like environments. How do we deal mentally with the isolation far from home, the confinement, monotony, and life in a small international crew? The experiences and stressors that crews face during such missions require a certain degree of mental resilience, or may otherwise result in cognitive or behavioural problems and a loss of performance that can be dangerous to both the crew and the mission. To facilitate such psychological adaptation and resilience, the scientists behind MINDFULICE (‘role of mindfulness disposition in an isolated and confined environment’) for example are investigating the use of ‘mindfulness’ as a tool for deep space missions. ‘But isn’t that something for Buddhist monks?’, I hear you question… I actually like to think it is quite the opposite. And although maybe it isn’t an easy construct to grasp, we are all already mindful to a certain degree. Perhaps it is best to think of it as a mental process, of being aware in the present moment, welcoming what is new with an intention of kindness and compassion, and being open-minded enough to see new possibilities in any given situation rather than relying on what you have previously learned. Everyone does that to a certain degree, but everyone can also learn to do it more. Perhaps that is the biggest reason that the concept is gaining so much popularity so quickly. In our stressful and busy lives, mindfulness helps us to see solutions rather than problems, and research has already demonstrated many of its benefits, spanning from health and well-being to even business and artistic endeavours! A mindful attitude has shown to reduce stress while increasing resilience, task performance, enjoyment, psychological and even physical well-being, and in general a higher quality of life. That, I would say, is the promising power of the mind! So can mindfulness also help astronauts to cope with the harshness of a deep space mission? We like to think so, but to find out we must first understand how it relates to stress and psychological wellbeing in such conditions, and Concordia serves as the ideal testing ground. Of course that means more tests for us, so over the year we fill in questionnaires and perform attention tasks to determine how mind- and stressful we actually are. And how about you? Are you mindful enough to one day float to the stars? Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here.

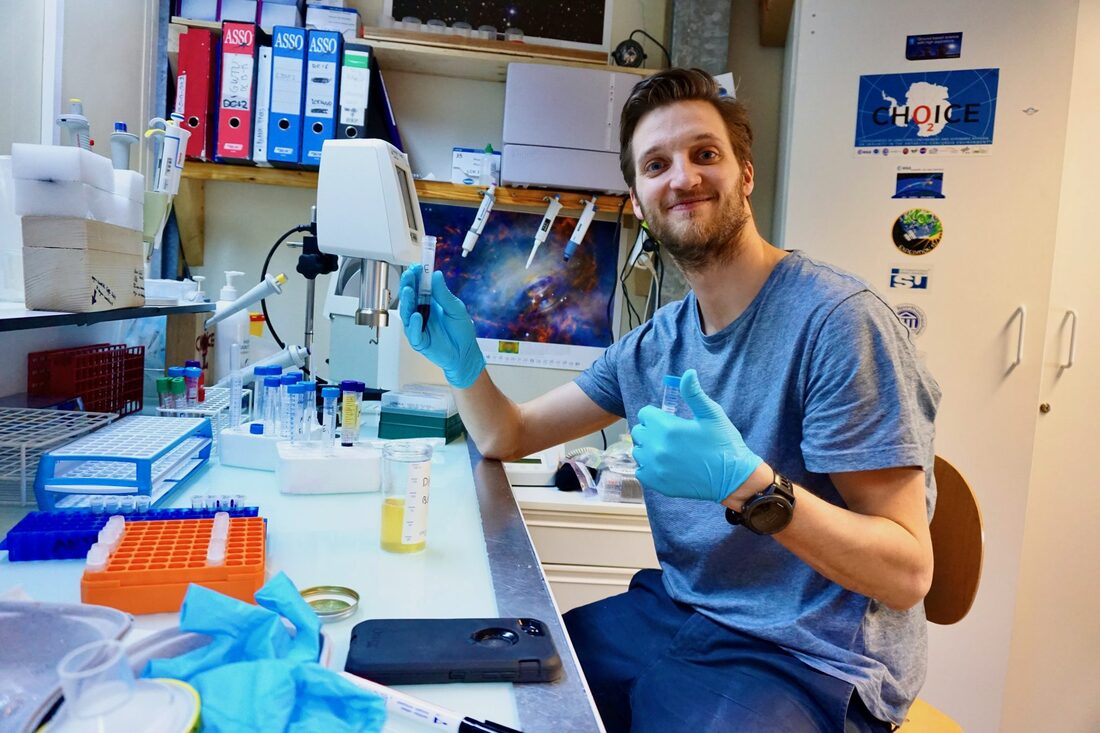

The next instalment of a fascinating blog series by ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen who spent a year at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica And so we keep delivering. Questionnaires about stress, physical and mental wellbeing, questionnaires about nutrition habits, stool samples, saliva samples, blood samples, taste tests with taste strips, smell tests with ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’. I make pictures of what I am eating twice a day, and our cook records our menu a whole year long. And, perhaps best of all, we all take a sachet every day, without even knowing if it contains a probiotic supplement, or nothing but just powder…  ‘This reminds me of the dentist. And this of flower fields when I was young. And this one is industrial banana for sure!’ The ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’ induce vivid memories, but do our smell and taste change in this understimulating environment? And how does that relate to our eating habits? Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–S. Thoolen This time the tests are for another study called ICELAND (‘immune and microbiome changes in environments with limited antigen diversity’). ICELAND doesn’t focus on altitude, but instead uses the homogeneous environment of Concordia, another stressor to our body and mind, as a testbed for examining changes in immune health. Have you ever thought of the idea that, just like in Concordia or in space, a lack of new bacteria and viruses can actually deteriorate your immune system? Have you ever considered that we may be too hygienic? Just like losing muscles when we spend too much time on the couch, or losing skills if we don’t practice our brain, we can lose immune function when it is not stimulated, and according to the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ this may be one of the reasons for an increased incidence of asthma and skin inflammation in children in developed countries. In a similar way, prolonged isolation and confinement in the stressful and ‘clean’ environments of Antarctica or space is thought to increase susceptibility to infections and even allergies! But the immune system is complex, and the many interactions it holds with other body systems such as our digestive system and our brain are just being discovered. For example, changes in nutrition can have an effect on the composition and health of our gut bacteria, which in recent years have been found to play an important role in the development of immune-related diseases such as allergies and cancer. Other studies in addition have found gut health to be related to mental wellbeing as well. So can we maintain a healthy brain and a healthy immune system if we maintain a healthy gut? We still have much to learn about ourselves, and ICELAND aims to investigate these interesting interactions. Hence those daily sachets: comparing the test outcomes between those of us who took gut bacteria-stimulating probiotics and those who didn’t can give us valuable information about its potential to counter these health risks! Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here.

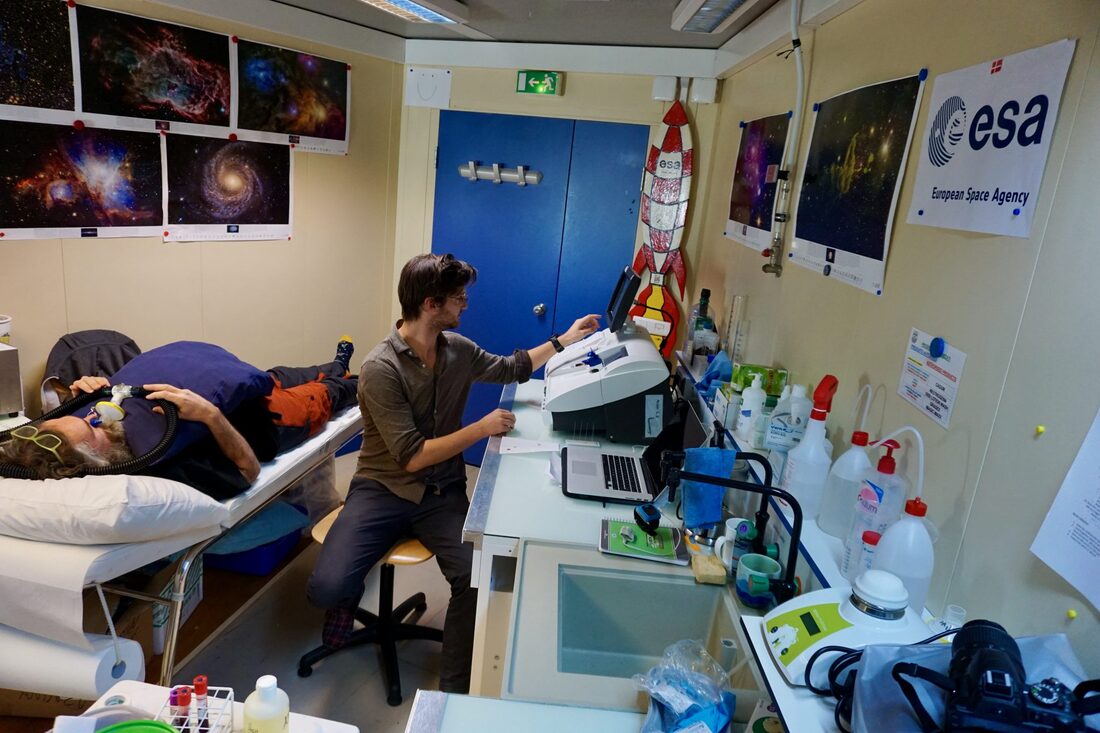

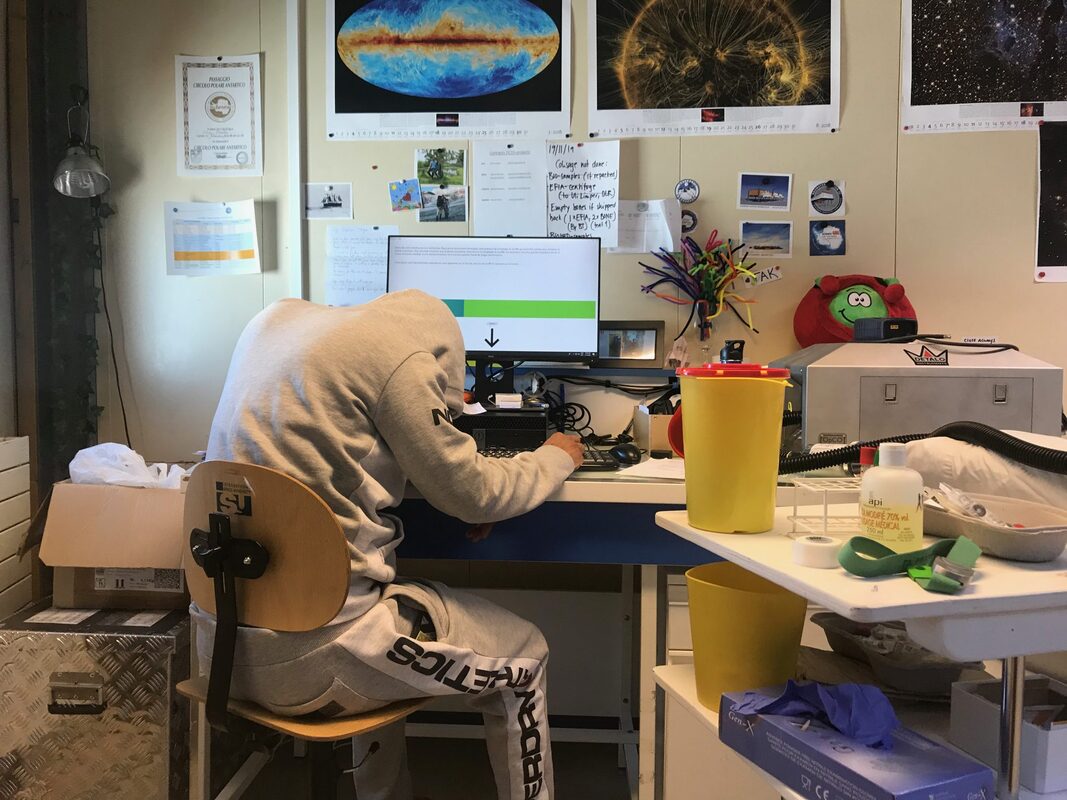

The fascinating blog series chronicling a year in the life of ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen at the Concordia research station in Antarctica continues. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Concordia, July 28, 2020 Sunlight: none, but the skies are turning colours again! Windchill temperature: -83°C Mood: some days a little tired, and on others, like the skies, full of colour If you have read my previous posts, you have probably had enough of the beautiful-environment-and-working-together-drivel, and I am guessing you are now thinking something along the lines of: weren’t you supposed to do space research? Good question, and it makes me realise that perhaps it is time for something more interesting: science! But I am not sure if an ESA blog can go without any music, so before we continue here is a nice tune to walk you through:

Take, for example, the altitude. Here in Concordia we live at an altitude that is equivalent to about 3800 meters above sea level at the equator. As such, it's as if the air were to contain about 40% less oxygen for us to breath, and you definitely feel that when you arrive here by plane. Low energy, panting with the slightest exercise, waking up gasping for air multiple times a night, headache, dizziness, loss of appetite. Some really get sick from it, and in rare cases people have to be sent back to the coast due to life-threatening build-up of fluid in the lungs or brain! Yet, in 1978 Messner and Habeler reached the summit of Mount Everest at an altitude of 8848 meters without using any supplemental oxygen at all. How? They allowed time for their bodies to adapt. At Concordia it usually takes a few days before you feel better. As your body senses a decrease in oxygen pressure it immediately tries to save your cells from getting damaged by sucking in more air (breathing) and pump more oxygen through the body (by increasing heart rate), and subsequently starts up a remarkable cascade of physiological processes that eventually leads to an increased production of red blood cells. As a result, the composition of our blood can drastically change over weeks, to help deliver sufficient oxygen to each of our cells. Pretty cool, don’t you think? Even though after eight months I still find myself hyperventilating up the stairs and having miserable nights every once in a while, at least it allows me to go to beautiful places like Concordia! The adaptation however comes with a trade-off: if the need for oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood is too high (at higher altitudes, where there is less oxygen) and too many red blood cells are made, the blood can become so thick that it increases the risk of blood clotting, high blood pressure in the lungs, and even heart failure! Such health issues have been seen in some people living permanently at high altitude. So how healthy actually is a year of adaptation at Concordia? Knowing that similar low oxygen conditions may exist in future space habitats for technical, economical and safety reasons, and considering the simultaneous blood volume alterations usually seen as an effect of microgravity, answering that question is important to understand astronaut health and safety during future long-duration space missions. The ANTARCV study (‘alterations in total red blood cell volume and plasma volume during a one-year confinement in Antarctica: effect of hypoxia’) is implemented this year to do so. Each month the crew comes to the ESA lab for a lucky treatment of vein punctures, and an awkward procedure of breathing a very small and safe dose of carbon monoxide through small, restrictive tubes. This way I can determine our blood volumes. Besides I analyze how thick our blood is, store blood samples for further analysis in Europe, and we all wear a watch one week a month to record our activity. That way we make sure that the changes we see in blood volumes are not just a result of changes in physical activity. You can understand the crew loves me for it…  ANTARCV on full speed. By administering carbon monoxide and determining the increase in its concentration in the blood, we can calculate how many red blood cells are circulating through the body/ANTARCV op volle snelheid. Door koolstofmonoxide toe te dienen en de concentratietoename te bepalen in het bloed, kunnen we berekenen hoeveel rode bloedcellen er door het lichaam circuleren. Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–S. Thoolen Still, all of us are participating in the research, and that is awesome! You see, doing human research here can be quite a challenge, not only because of language barriers, limited data transfer possibilities, or complex transportation logistics, but mostly so because the participation in these experiments is entirely voluntary. None of us works here primarily to serve as a test subject, and it is not that I can force anyone really… So to make sure I come home after a year with sufficient interesting data, I better make sure that everyone is happy with what we are doing here. For me perhaps a tricky mix between work and private life, but all for the good cause of science! After all, who doesn’t want to be part of the space program, bring benefit to future hivernauts and astronauts, and on top of that help to understand health challenges of our present-day society? Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here.

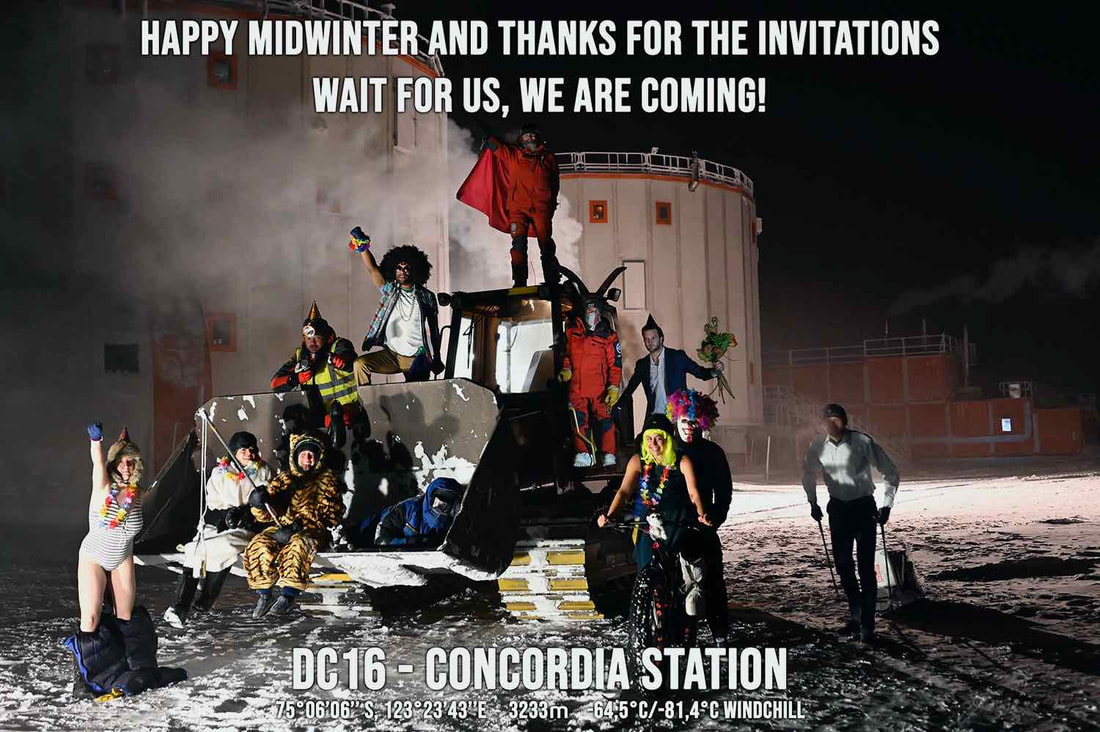

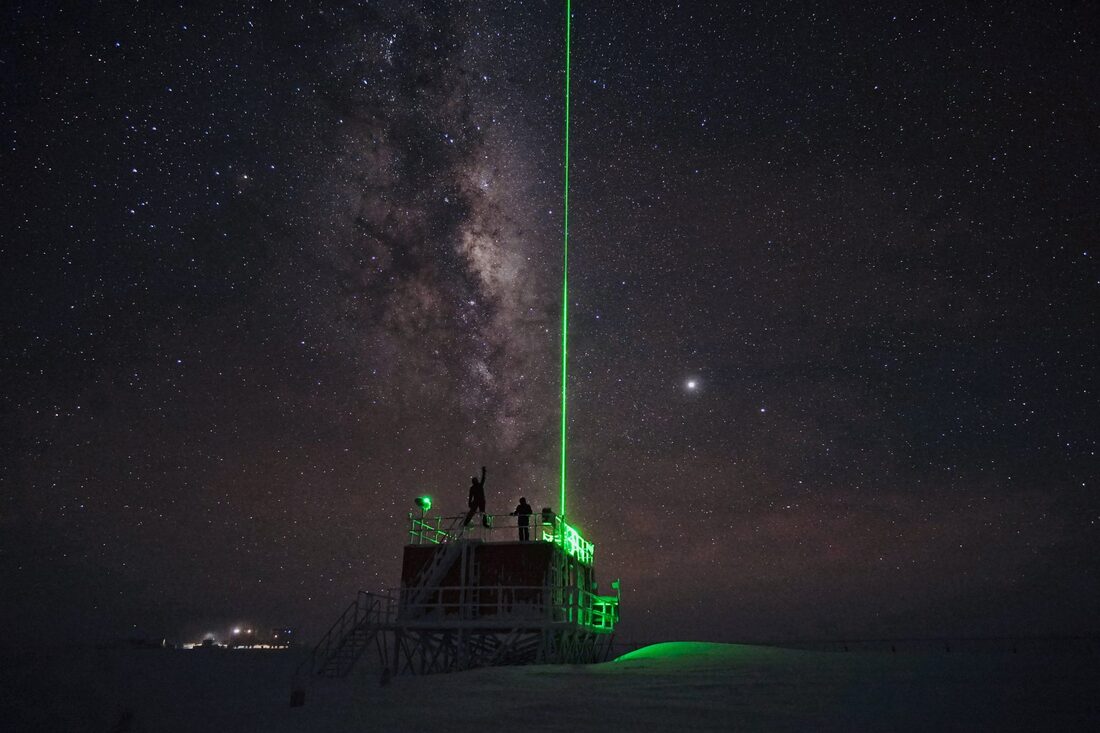

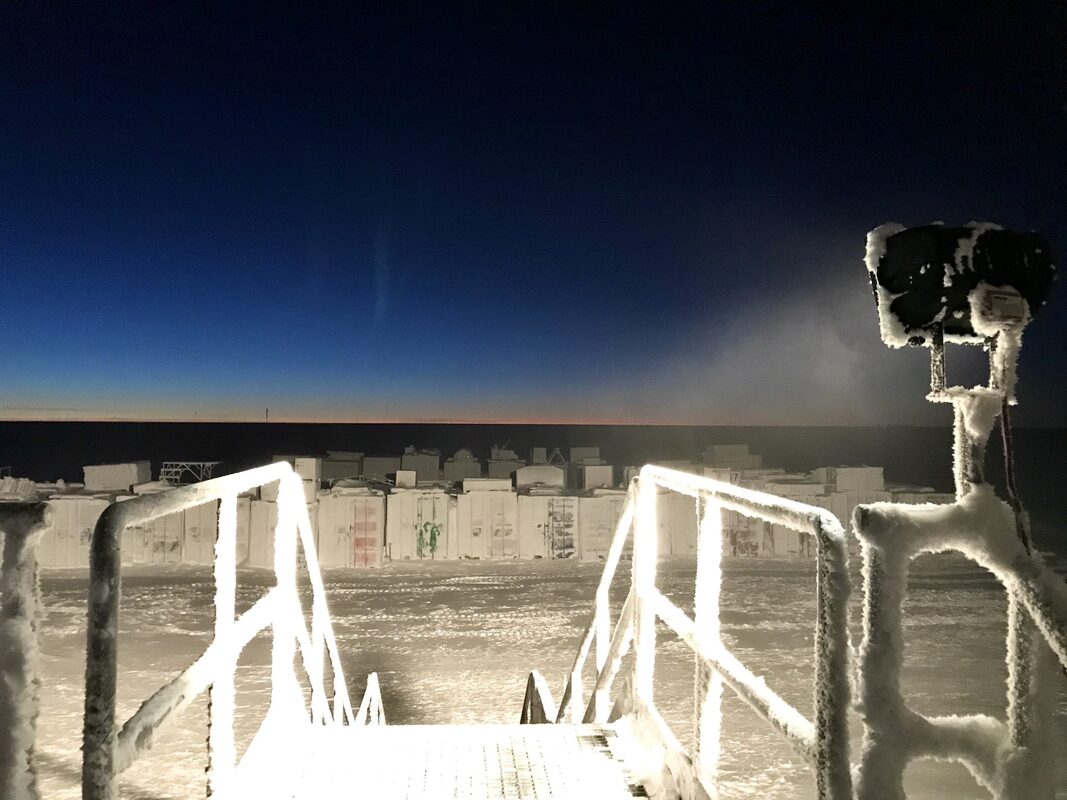

We welcome back ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen, as he continues his tales of life at the Concordia research station in Antarctica, in the harsh environment of the world's southernmost continent. If you have missed them, do check out his earlier blogs, complete with wonderful photos - Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5 Dr Stijn Thoolen Medical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Concordia, July 10, 2020 Sunlight: none Windchill temperature: -84°C Mood: still OK The Antarctic winter solstice is special. As the Earth’s south pole is maximally tilted away from the Sun and the longest night falls over the southern hemisphere, people everywhere and since prehistoric times gather in tradition to celebrate the change of season and welcome the return of sunlight. But for a bunch of lost scientists and technicians on the Antarctic continent, that longest night lasts much longer. They won’t see any Sun for another one-and-a-half months. For them, mid-winter marks not just the gradual return of daylight, but much more so the midpoint of an extraordinary nine-month winterover adventure. So it is an important moment. A time for celebration and for reflection (or perhaps just celebration…). To me it looks a little like Christmas, or New Year’s Eve, but with a twist perhaps (we are winteroverers, after all). Presents, dinners, parties, and (digital) mid-winter greetings from all the other Antarctic stations, kindly inviting us to come over to celebrate together. ‘The door is always open’, ‘generous parking space for motor vehicles and sledges’, ‘plenty of accommodation with ice sea vistas’, ‘bring your sleeping bag’, ‘COVID-19 free’. Anyway, you get the much-needed humour.  Our response. With -80 degrees Celsius windchill we didn’t get any further than several meters from the station. Credits: IPEV/PNRA – S. Guesnier Our response. With -80 degrees Celsius windchill we didn’t get any further than several meters from the station. Credits: IPEV/PNRA – S. Guesnier At first I wondered: being here only for about half a year now, how can such a completely new thing already hold such importance to people? No ritual, no guidelines, no one really knowing how to celebrate it, and yet the expectations are high in our crew, and the ideas plentiful. But looking back I have to admit: mid-winter is a beautiful tradition, even though never celebrated before… While hints of daylight can be spotted on the horizon around noon, there won’t be any sun for another one-and-a-half months. Winter can be harsh, without sunlight, far away from home, and with the same twelve people, for such a long time. And even in such an interesting and beautiful place, also I have recognized a few moments of disappointment. I guess, with all those different backgrounds and being the only Dutch around, it is not always easy to feel understood. Or perhaps it is just me who is getting a little less tolerant, in higher need for emotional support. And while that doesn’t make life always easy here, I recently read a beautiful sentence: ‘Do not worry that others don’t understand you. Rather worry that you don’t understand others.’ Can we still bring up that flexibility to try to understand each other, in a world where we are tempted to blame our problems on all but ourselves? On the ethical playground of Concordia, where walking away is out of the question and a lack of group cohesion can have direct consequences to our own wellbeing, I like to believe it is essential. And wasn’t this exactly what I was here for? To learn to become a better person? With such thoughts in the back of my mind and realizing we still have another half to go, mid-winter then becomes the perfect excuse to work a little on ourselves. To do an extra effort for each other, give rather than ask, and just share some fun. To collaborate in a positive way to get closer as a group, building that tolerance for each other again, and making us all a little more willing to see the best in each other. And as such, music went back on loud again, and we went to work… Brazilian night complete with exotic travel stories (you can imagine how popular these become here) and table soccer tournament, quiz night, cheesy fatty Alpine dinner, ‘kermesse’ games event including prizes to win, a spa (our hospital doctor decided that we could give the hospital a better use for the winter months), the first Antarctic championship of the traditional Italian game ‘Ruzzolone’ (Google it, and let your imagination do the rest), and, for once this year, an opportunity to actually go out for dinner (we eat in the same room all year long) in our ‘McDome’ fast-food restaurant (you may know it better as the astronomy shelter…). Ordered by radio and served upon arrival. Burgers, chips, milkshakes, and amazing reactions from the rest of the crew: everything a deprived winteroverer needs! Mid-winter was great! Each of us participated to organize some of the festivities, and it kept us busy for sure. We celebrated five days full of the most ridiculous activities, and we were all exhausted afterwards. I guess that all these efforts may seem trivial back home, and the details may not look like much from the outside, but here I feel it is pretty important to us. These ridiculous activities bring variety, make us smile, and get us fueled up for another four-and-a-half month together. These will become the memories that we take home after a year on ice, and I think that makes mid-winter worth all the effort! It makes me wonder how I will feel after a yearlong of practicing the much-needed tolerance and social consciousness here in Concordia: do we put the same amount of effort in each other at home? Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here.

ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen, currently spending 12 months at the Concordia research station in Antarctica, presents the next blog in his series recounting tales from his time spent in the harsh environment of the world's southernmost continent. What an amazing experience - do take a look at his previous blogs (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4) to follow his great adventure!

Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica

Concordia, April 7, 2020 Sunlight: about 10 hours Windchill temperature: -72°C Mood: just fine  Greetings from paradise! Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–S. Thoolen Greetings from paradise! Credits: ESA/IPEV/PNRA–S. Thoolen

It is quite strange to be here, on the only continent not affected by the corona virus. To me, with everything that is currently going on in the rest of the world, it makes feel even more distant than we already are. Here, life just goes on, and although it has not been easy for some of us either, not being able to share in these experiences or provide support at home to those who could use it, messages are now suggesting that we are suddenly the ones better off!

And I have to admit indeed. Even though we are stuck here for nine months without any possibility for evacuation, with limited resources, a disrupted work/leisure balance, a threatening environment outside, both environmental and social monotony, and a group of relative strangers that come from all sorts of backgrounds (reading this I guess the situation for you may perhaps not be so different), at least we came here by choice…

So let me start with saying that I really hope you are doing well. Being isolated and confined comes with all kinds of stressors, deviations from the normal situation you could say, that ask our body and mind to adapt. Given the sudden disruption that the Corona outbreak has caused to all of you, I imagine that is certainly not easy.

And while our experiences are so different, and even though I feel probably as ignorant as you about how to deal with all those stressors (we have just been left to ourselves two months ago), perhaps this is a good time to share with you some of my own thoughts about isolation at Concordia.

A while ago I came across a story about the 1897-1899 Belgian Antarctic Expedition, which I found quite illustrative for what I have considered to make my winterover a happy one this year. At the time the Antarctic was still mostly unknown territory. The south pole was not yet reached, and the unforgiving environment made many expeditions end in disappointment. Aimed for exploration and for science, this one was no exception. When their ship the Belgica got stuck in the pack ice of the Bellingshausen Sea, the 19-member crew became the first in human history to winterover below the Antarctic circle, and as such you can imagine they were badly prepared to do so. It must have been pretty difficult, I imagine. Expedition doctor Frederick Cook described depression, irritability, headaches and sleeplessness among the crew, and basically provided a first recorded description of the so-called ‘winterover syndrome’.

“The curtain of blackness which has fallen over the outer world of icy desolation has also descended upon the inner world of our souls” – Frederick A. Cook, 1900

The strange and extreme Antarctic environment, just like in space, indeed has a strong capability to upset our system. Symptoms like fatigue, headaches, sleep disturbances, impaired cognition, negative emotions such as depression, anxiety and anger, and interpersonal conflicts have all been observed in polar dwellers. Such symptoms are usually more prevalent during the harsh winter months, when stressors are highest. Hence the ‘winterover syndrome’. For the winterover crew of 1898, Dr. Cook reasoned that what they needed that was the opposite of that harsh winter environment. Apparently with good effect, he prescribed them a diet of milk, fresh meat (poor penguins) and cranberry juice, as well as exercise, warmth and light. Interesting I think, not necessarily his particular ‘baking treatment’ of having the crew sit naked around an open fire, but the way it shows how dependent we are on our environment, and our limitations to adapt. In other words, to facilitate adaptation, we may want to create an environment that is more familiar to us.

For here in Concordia, or perhaps for something as different and unexpected as a Covid-19 lockdown, I like to think the idea is quite similar. I therefore try to maintain a daily rhythm full of activities that mimic a little bit the world we come from. I try to wake up and go to bed at regular times to promote sleep and maintain a functioning biological clock (without sunlight it relies even more on social clues), and while I restrict myself as much as possible from bright computer screens in the evening hours, an artificial daylight is standing by in my office for the darkest months. Elisa, our cook, is making us pretty balanced meals twice a day, and even though I have to admit I eat a lot here (altitude plus cold equals many burned calories), I take vitamin D in addition to make up for the lack of sunlight. About three times a week I visit the gym (it got a little too cold outside) to stimulate myself physically, and if not working, sleeping, eating, or exercising, I try to stimulate my senses by an impact from the magnificent world outside, playing games together, or reading a book. Socially, I try to stay connected with my friends and family at home, and with the crew we regularly have video connections with schools for outreach purposes, and even with each other’s families. We are social beings after all, and we may easily become lonely if we don’t feel part of the group (whichever group that may be…). Finally, to relieve some of the excess amount of stress here, I try to practice meditation each morning, and for the same reasons we have our sauna (yes, sauna) open on Sunday’s. Perhaps it really is a paradise…

We welcome another blog by ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen, currently spending 12 months at the Concordia research station in Antarctica conducting experiments. What an amazing experience - do take a look at his previous blogs (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3) to follow his great adventure to the world's southernmost continent.

Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica

Concordia, February 7, 2020

Sunlight: 24 hours (but not for long) Windchill temperature: -45°C Mood: a little roller coaster At this moment I am just plain excited. Next to me the rest of the DC16 crew are having their own emotions. Our freshly inaugurated station leader Alberto, draped in the colours of our three national flags, came up with the idea to have our national anthems playing while the last Basler plane of the summer campaign leaves Dome C. So here I stand, hearing my own voice on maximum volume pronouncing a Dutch translation of too patriotic sentences from the station’s speakers, and with the Dutch ‘Wilhelmus’ screaming over the Antarctic plateau as an official start of our winter over. Haha, such an unrealistic scenario! And while those sounds are quickly overruled by the roaring engines of the plane, and with snow blowing in our faces, I can only smile. There goes our last connection to the rest of the earth, disappearing into the distant sky. Unbelievable!

I guess I have already spilled all of my emotions at this point. In the past few days, more and more planes have been taking away more and more of the beautiful people we enjoyed our summertime with, and the station has become more and more empty. Funny: they were already leaving, and I have the idea we just started… It has been an exciting idea on the one hand, but the closer we came to being left alone, the more and more confronting that got on the other. When two days earlier another plane left with sixteen more people, the goodbyes were harsh, with everyone in tears again. You know, those healthy ones. And when it was gone, those left on the ice slowly returned back to the station, all silent, all caught in their own thoughts. It had been an intense few summer months, and this was the weird moment of realization that it had come to an end, with a big unknown lying ahead. I guess the blend of feelings has been a repetition of those during the days before my departure to the Antarctic. Perhaps a little lighter this time.

Mary UpritchardInnovaSpace Co-Founder & Admin Director

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed