|

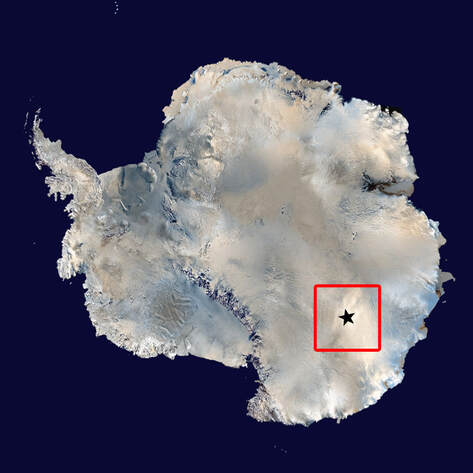

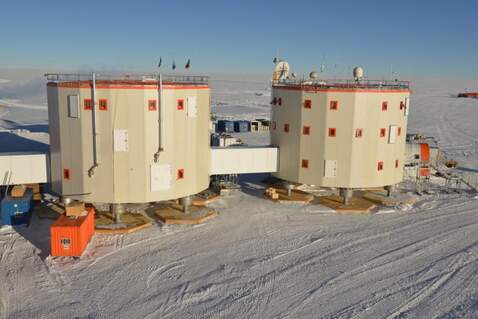

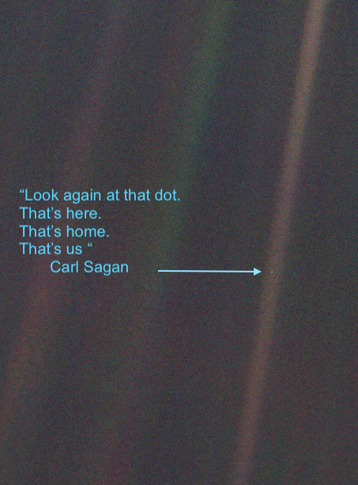

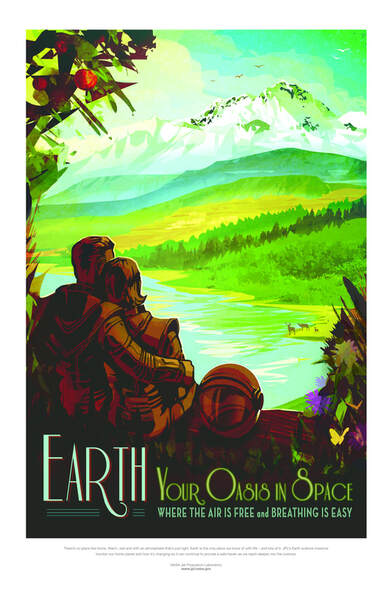

InnovaSpace is pleased to welcome Dr Stijn Thoolen to tell us more about life at the Concordia Research Station in the Antarctic, an extreme environment where temperatures can fall below −80 °C (−112 °F) in the winter months. As an ESA-sponsored medical research doctor, Stijn will remain at the Franco-Italian research station for 13 months - definitely not an activity for the faint hearted! Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica  Location of Concordia Research Station. Credits: ESA Location of Concordia Research Station. Credits: ESA 75 ° 05’59 “S; 123 ° 19’56” E. I will spend 13 months of my life at these coordinates from November onwards. Far away from my girlfriend, my family and friends, from everything that I know and have loved for the past 28 years. A small 1700 km away from the South Pole, situated on a 3270-high ice sheet, with 40% less oxygen than at sea level (the atmosphere is thinner at the poles), a humidity lower than in the Sahara, average temperatures of –30°C in summer and –65°C in winter, four months without any ray of sunshine (is this lunchtime, or should I go to bed already?) and without possibility of evacuation for nine months, the Franco-Italian research station Concordia on Dome C in Antarctica sounds more like a base on another planet. Every year the European Space Agency sends a ‘hivernaut’ (a winter version of an astronaut?) to this abandoned outpost at the bottom of our globe to perform biomedical experiments on the crew, in preparation for missions to the Moon, Mars and who knows what’s next. This year it’s my turn, and those 13 months are starting to get awfully close… I hear you ask: why (…would you do that for God’s sake)? “In our history it was some horde of furry little mammals who hid from the dinosaurs, colonized the treetops and later scampered down to domesticate fire, invent writing, construct observatories and launch space vehicles” – Carl Sagan  ‘White Mars’, ‘planet Concordia’, you name it. Credits: ESA ‘White Mars’, ‘planet Concordia’, you name it. Credits: ESA I sometimes ask myself that question as well, but you can imagine that the answer is as obvious as the undertaking itself. Maybe we should start with a short self-evaluation: Self-evaluation is not something we often do. At least, I was never good at it. When everything goes according to plan, and everyone around you screams how wonderful it is that “little Stijn wants to become a surgeon!”, you aren’t really encouraged to take a critical look at yourself, right? But sometimes a shock (or two) helps to adjust a bit. A lesson in humility perhaps. For me, that first shock came about five years ago. I had said “yes” a little too much, a good friend died, my parents divorced, and with about ten suitcases of mental luggage I left for a research internship in Boston, USA, during my medical studies. In such a new environment, full with material to reflect on, things became a little more relative. I realised that nothing is as obvious as it seems, that some things might actually be bigger than us (the Universe, God, the flying spaghetti monster, you choose), and, even better, how beautiful and special it is that we are able to witness all that (I know this sounds dull, but I dare you to try with your eyes fixed on a bright, starry sky).  The photo “Pale Blue Dot” (our Earth) was taken in 1990 by the Voyager 1 space probe on the edge of our solar system, a small 6.4 billion km away from us. Credits: NASA The photo “Pale Blue Dot” (our Earth) was taken in 1990 by the Voyager 1 space probe on the edge of our solar system, a small 6.4 billion km away from us. Credits: NASA Everything is interconnected, everything changes, and the desire to feel part of that has increased continually. When I look at Carl Sagan’s quote again (the first one) with that thought, spaceflight takes on a whole new meaning for me. We are currently living in the space age. The permanently-inhabited International Space Station has been flying around Earth for almost 19 years, China wants to launch the first module of its space station next year, Trump is pushing NASA back to the Moon by 2024 with the new Artemis programme, ESA is designing a Moon village, SpaceX is on its way to colonise Mars. It is perhaps somewhat comparable to the centuries when the first ships sailed away from our coastlines. We are pushing our limits step by step, and now, for the first time in the history of life as we know it, life is leaving its birthplace. Quite special, right? How exciting, and what a great time to be alive! But if only exciting, I might as well just go for another bungee jump. No, I like to believe that pushing those boundaries will bring us much more.  Would you fall off the Earth? It was hard to imagine what exactly to expect… Ludolf Backhuysen, “Hollandia” (1666 – 1667). Would you fall off the Earth? It was hard to imagine what exactly to expect… Ludolf Backhuysen, “Hollandia” (1666 – 1667). Space travel is often defended “ because we have to save humanity from overpopulation or mass extinction”, or “because it brings all sorts of new technologies” (think of telecommunications, Earth observation, but also health care), but neither do I think that those arguments should be our first concern. We have bigger problems to deal with. What I find most compelling is that feeling of wonder – spirituality, if you wish – that astronauts and cosmologists talk about: the so-called “overview effect”. When the first Apollo astronauts returned from their trip around the Moon in December 1968, one of them came to the following conclusion: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”  It’s pretty special here… Credits: NASA It’s pretty special here… Credits: NASA What can we learn from our efforts, and what do they teach us about ourselves? The observations we make in space travel and astronomy give us a tremendous opportunity to appreciate how vulnerable we actually are, a rather insignificant mote of dust in a remote corner of a lonely galaxy that will only exist for a few seconds on the cosmic calendar. This is “spaceship Earth,” flying through the universe of time, and for a brief moment we are among its many passengers, more dependent on each other and our environment than we sometimes want to think. A lesson in humility after all, driven by curiosity. Spaceflight brings new perspective, and what do we need more than that these days? With newfound inspiration and some American dreaminess, I decided halfway through my studies to follow my desire, and plunge into an exciting, discovering – but also the socially and environmentally conscious – world of space medicine. Yes, space medicine. It is quite cool, all those responses I have had in the past few years. From “Does that exist? Okay…?” to “Wow, cool!”. With most of the “wow, cool” people though, it was evident that they didn’t know much about it either. It’s hard to imagine, but space medicine could soon become the new standard. There is still plenty of work to do before we can shoot ourselves to Mars in a somewhat responsible manner. No matter how interesting and educational space travel is, and how eager we are, what’s in our way is that we are not built for it.  Space travel is not easy for the human body, but also not for the mind … Credits: ESA Space travel is not easy for the human body, but also not for the mind … Credits: ESA We belong on Earth, raised under the influence of exactly 9.8 m/s2 gravity, cosily in a wet and warm atmosphere, at a particularly pleasant distance from the Sun, with friendly temperatures of around –40 to +40°C, together with our companions, and preferably with not too much food and drinks available so that we occasionally also have something to do. If we wander away, our ability to adapt reaches a limit. Thus, humans are not used to the extreme conditions found in spaceflight. Our sense of balance gets disturbed, we get motion sickness, we get anaemia, our hearts shrink, muscles break down, bones waste away, sometimes eyesight gets worse, and we become prone to infections: actually it is just as extreme as chilling on the couch for a few days. And we haven’t even talked about radiation exposure, and the psychological consequences of a trip through space, far from home, locked up, without fresh food, and your colleagues struggling with all this just as much as you. What would happen to you if, during such a journey, you lose sight of Earth, with on it everything (really everything) you learned? If we want to be able to take the next step, research is essential. This is why the extremes at Concordia are so interesting, as an analogue for future life in space. It is a unique place on Earth, where we can already investigate conditions of isolation and confinement in extreme environments for a fraction of the costs of spaceflight. It is farther away from home (both in distance and in travel time) than the International Space Station, and resources are limited. If something happens to us, we can figure it out by ourselves and some help from the medical help desk in Rome for nine months. The circadian rhythm is abnormal, the environment is monotonous, and living with only 12 colleagues will be both socially and sensory depressing . Are you starting to understand why I’m so excited…? For many people it may sound strange, but I like to see Concordia as an opportunity, a new challenge. I once came across this line from Anaïs Nin, that could be appropriate here: “And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom” Sometimes I get the idea we want to keep everything the same. It feels nice and safe if the world is predictable, and from an evolutionary point of view we undoubtedly needed this to recognise the dangers around us. As we grow older, that truth begins to cement itself into a big chunk of unquestionable truth that we are afraid to lose, but I am afraid that sooner or later (or perhaps continuously?) there will be times when we have to let go of that control. An extreme example: we spend most money on health care during the last years of our lives and struggle with it until we die. I guess sometimes you should just go for it, and embrace the challenge of something new just like my almost-two-year-old nephew. Then, we will embrace that change forms the basis of our growth, of the learning process, and that it is a necessity actually, of life. Out of comfort zone (quite literally this time) we broaden our perspective, and learn how to deal with the changes that are still awaiting us. Hopefully, one day I will also lie on my deathbed, but only proud with a feeling of pride of what I have been able to leave behind. So I’ll take experiment Concordia. An experience, that shock I think, to learn from, just like those astronauts and cosmologists … Time for some music (turn it up if you want), to finish in style: Anyway, enough blabber for now. After five letters of application from the first time I heard about the Concordia programme as a medical intern in early 2015 (haha, what was I thinking!), two research internships in aerospace medicine, an ultra-marathon through the Moroccan Sahara and a few more travel and outdoor adventures, another study in space physiology, nine months in the emergency room, two job interviews in Paris, some strange psychological tests and a diligent collection of medical examinations, this time I finally succeeded (I still think I was selected this time, just to prevent me from knocking on the door next year again…).

After a little happy dance and one of the fastest jogs around the block ever, my energy had dropped to acceptable levels, and with this beautiful news that on the first of April (could it really not be a joke?) the direction was finally set. I quit my job, stopped the rent, sold my car, and since a few weeks preparations are in full acceleration (and let’s save that for the next report) I’m getting more and more curious. What will Antarctica do to me? How will I feel down there? What effect will this have, not only on me, but also on the people I love, and how will we all deal with the experience? It is hard to imagine what awaits me there, and that actually already makes it quite beautiful. I just keep in mind that there have been few Antarctic winter-over-ers who regretted their endeavour. Then maybe Concordia is not so crazy after all… Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here. Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

InnovaSpace Ltd - Registered in England & Wales - No. 11323249

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed