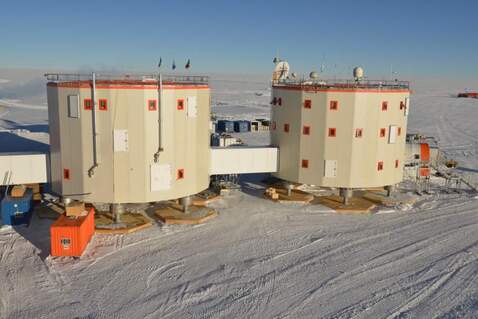

Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Ever fancied spending some time in Antarctica? If so, take a look through the writings of Dr Stijn Thoolen, an ESA-sponsored medical doctor spending 12 months at the Concordia research station. His photos will either inspire you to go do it, or remind you of how desolate and EXTREMELY cold it is! Do take a look at Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of his blog series, talking about his time at the world's southernmost continent. Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica

It is a beautiful summer day. There is even less wind than usual (with constant summer temperatures, almost always a blue sky and few weather changes, we are mainly concerned with wind), so I am not afraid to go outside in my t-shirt today. The sun reflecting off the snow is attacking me from all directions, and I will most probably burn, but I don’t care. It may be my only chance this year (and I imagine that in a few months I will look back on this day just like you must now look back at those days at the beach, or under the green trees, in the warm sun…). It is busy in front of the station. To the left, an empty rack is being carried away, to the right boxes are sorted, behind me a human chain is carrying them away into a container, and in front of me the green “Merlot” hoists the heaviest stuff. The chaos has something of a busy market on the village square (but then just a little different). Everyone is helping to organize those few 1000 kilos of food brought in by the overland traverse. It had arrived here yesterday, finally, after a day or ten on the ice. Huge logistics. You could say that all that food has arrived just in time, after that monstrous New Year’s Eve dinner two days ago (never seen so much food, not enjoyable anymore). But now that I see with my own eyes what is being stored in those containers and in the station, I am confident we won’t starve this winter. Summer feels like one big party. I have installed myself in the ESA lab by now, as well as within our DC16 crew, who are all still happy to participate in the biomedical research projects (the ESA lab is also a party). Every few days another plane comes in to deliver a new load of guests or equipment, and pick up old ones. Nobody lives here permanently (although some are almost considered part of the furniture after too many summer campaigns). We are all guests, and we are all working towards one common goal: knowledge. There are currently around 70 people here at Concordia, a beautiful collection of the most diverse backgrounds but with that same goal, and all of us equally idiot to think that Antarctica is interesting enough to leave the comfort of home for. Seismologists, carpenters, glaciologists, climatologists, electricians, mechanics, meteorologists, astronomers, plumbers, physicists, physicians, cooks, ICT specialists, a cleaner, and a station leader. It makes for a lively experience and ensures that there is plenty to discover besides writing blog posts. 35 scientific projects are being carried out here this summer. Every day a weather balloon is released at an altitude of approximately 30 kilometers to contribute to our weather forecasts. In a cave 12 meters underground measurements are taken as part of a global earthquake observation network. ESA has installed instruments on the 40-meter high “American Tower” to communicate with satellites that monitor our Earth from outer space. A laser shoots into the air several times a day to better understand the properties of our atmosphere. At the same time, telescopes try to detect new planets that orbit around neighbouring stars lightyears away from us, and somewhere else again radioactive particles are being watched, reaching Concordia from outer space and from our Sun. Based on the physical and chemical properties of collected snow, we learn how our climate has changed over the years and what effects that can have on our future. Did you know that you can find traces in this snow of an Indonesian volcanic eruption from almost 60 years ago? And traces of last century’s glory days of nuclear bombing? What happens on the other side of our planet even has its consequences all the way here, at the end of the world. And so there is “Little Dome C”, our little brother, 35 kilometers away from us. In the coming years, the aim is to drill about two kilometers into the ice. Perhaps not as deep as the 3270-meter world record achieved by the historic EPICA project here at Dome C in 2004, but the ice cores are expected to be around 1.5 million (!) years old, allowing us to travel back in time twice as far. The ice here is actually a kind of diary of our wold, and we can learn what our planet’s climate has looked like before the Pleistocene (something relevant for reasons that I can’t full reproduce). Unbelievable! This place is one big special museum, where we learn about our past, and for our future. Not only scientifically speaking this place is a party. Concordia is also interesting from a cultural point of view. Apart from a few lost Americans and Swiss, everyone here is French or Italian. As we have already seen I therefore don't have to worry about the food (as opposed to my weight perhaps), and it is a luxury for improving my languages (and my table soccer skills). It is quite interesting to notice the differences, both in work culture and in leisure activities. With all those different people, every year again group formation unfortunately seems inevitable (it is always easier to stick to your habits), and while the Italians are being Italian and the French are being French, I am kind of stuck in the middle. Perfect. Not only because as a "neutral" person I have the possibility to oversee the whole thing a bit, but especially because it allows me to make a sarcastic joke here and there. There is more than just France or Italy, you know. Think for example about the "Spacca Ossa", perhaps the most exclusive nightclub of this world, and the glue of Concordia that makes us all feel like one again. It makes a beautiful scene for the Saturday night, of which I won’t share any photos with you. Our weekend usually starts on Saturday afternoon, and once scienced-out and done with partying, there is much more to enjoy: a home cinema, living room with pool and table soccer tables, an overdose of French comics (never knew that was a thing) and an even larger amount of music and films on the shared multimedia drive (interestingly enough mostly movies of bikini’s and palm trees are playing overtime on TV), a collection of musical instruments, board games, the “Atomic Sausage” (a fantastically crafted-together expired snowmobile that officially maybe doesn’t belong to this list), a gym, a game of rugby or volleyball outside in the snow, and I haven’t even unpacked my personal fun box yet. And then, to head back to the summer spirit and exploit these wonderful sunny days just a bit more, there is the beach. I will never forget the radio conversation that made no sense at all in the middle of all the seriousness: “Houston, for Stijn. We are going to the beach.” “Copy, Stijn”. So it’s a party. Sometimes this place feels like a three-star hotel, with everything you need available. Sometimes it all seems so normal, that I think it may make us spoiled one day. But at that New Year's Eve dinner two days ago, where everything was in abundance, I spoke with Vivien, our technical chef who is starting his second winterover in Concordia this year. This sense of certainty here is false, he told me, and he is right (is that music still on repeat? You may turn it off now). We are still at Concordia, one the most extreme and isolated places on earth. It is not difficult to imagine how quickly a small mistake can turn into a huge problem. What if the traverse doesn’t show up? What do we do without fresh food, or more important, without fuel? The “Astrolabe”, the ship that travels from Tasmania to coastal station Dumont d’Urville with all those supplies that are eventually brought to Concordia by the traverse, unexpectedly had to return for repairs early this summer. The entire logistics system was turned upside down, the traverse was delayed, and it was just hoping for a little while that we had sufficient reserves. And what if a fire breaks out? Or if someone gets sick? I myself have already hurried back inside a few times with pain in my fingers, and having seen multiple cases of frostbite, some fairly serious cases of altitude sickness (we have 35% less oxygen in the air than at home), and later even a car accident that could have ended much worse, I recognise how unforgiving this place can be. The monthly fire and rescue exercises may not be so bad after all. Slowly slowly I am learning about my own limits as well. I try not to be too impulsive (let’s forget about the snow dive at 3 AM last week), and carefully plan and experiment when I go outside. On Sundays I usually go for a run, and bit by bit I manage to keep my fingers and toes sweaty while I struggle increasing distances through the snow at -35 °C. Other gloves, spare goggles, extra batteries for the radio, an extra layer over the legs, but one less on top: it is a nice way to get to know this new, harsh environment. When I go running, it is often a few kilometers from the station. Completely wrapped to protect myself, I stare through my half-frozen glasses once again over that endless, motionless ocean of ice. Nothing on the horizon, barren, desolate, colder than anywhere else on Earth and no sign of life whatsoever, except for my own breathing. Typically these are the moments that make me realise it, just like during the trip to Little Dome C, or when collecting snow samples with the glaciologists far from the station. Then I realise where I am, and how vulnerable actually. Then all of it isn’t so obvious anymore indeed. But it is these moments especially that make me most enthusiastic about all this. Just having read a book about NASA's Apollo program, I keep thinking about what Buzz Aldrin had said the moment he first set foot on the moon: “Magnificent desolation”. To me, it describes it perfectly. It feels like a huge privilege to be able to live here for a year in this incredibly bizarre and desolate place. And while I hold on to that feeling, I can only fantasise about how extraordinary the winter must be. That hasn't even started yet... Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here. Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

InnovaSpace Ltd - Registered in England & Wales - No. 11323249

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed