|

Introduction from Eija Salmi, Secretary General, Cumulus Assoc. & Thais Russomano, CEO, InnovaSpace: During the 21st century outer space has become a topic for discussion by passionate people in design universities worldwide. Some institutions have piloted initiatives and have ongoing activities in the art, design and media curriculum focused on space, considering how design can contribute to overcoming the challenges humanity will encounter when exploring this new frontier. We know for certain that living off-Earth will bring multiple challenges that require innovative solutions if we are to inhabit another planet. The field of design will be an essential element in facilitating space life, just as it is present everywhere in our lives here on Earth, whether on its own or collaboratively with other disciplines, such as medicine, engineering etc. Design education and research plays a massive role not only for the design profession, but also for business, industry and other institutional stakeholders in the space era to ensure a good, healthy and secure space future. The aim of this blog today, written by Dr Dolly Daou, is to share knowledge and inspire all of us to rise to the challenges of humanity’s tomorrow in outer space – inspired by design. This is the first in a series! Enjoy and please do share on your social media! On Planet Earth, we have been accustomed to living our lives conditioned by daily habits; we eat, sleep, cook, work, walk, build, interact according to our environments, grounded by gravity. Culturally, we differ in customs, in habits, we eat different food, we live differently, we speak different languages, however what unifies us is the relationship between our physiology and our topography. This relationship is the result of the universal gravity system and the evolution of beings and their environment on Planet Earth, the Blue Planet. The colour blue refers to the interaction of solar rays with the gases of Earth's atmosphere. Similarly, Planet Mars is known as the Red Planet in reference to the mass of red soil that covers its surface. The colour coding of both planets reflects the relationship between our biological existence and our environmental characteristics, which influence our daily habits and our survival traits on these planets.

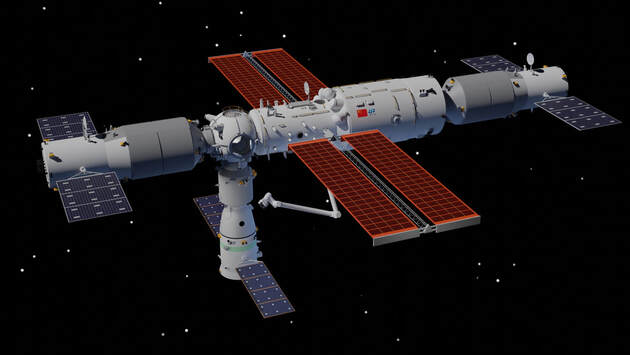

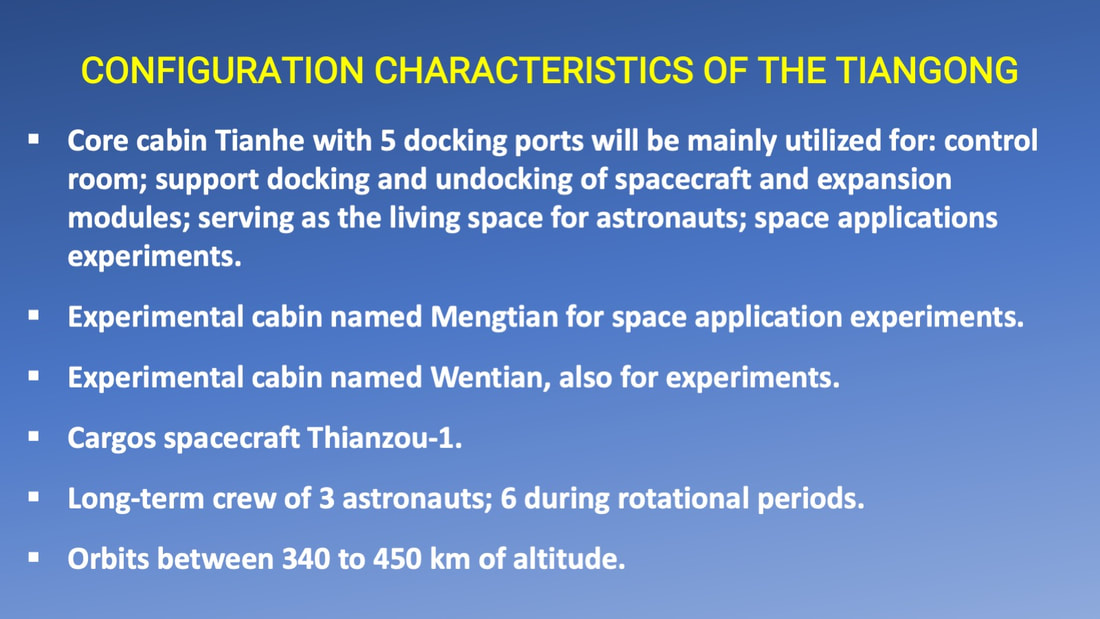

Author: Elias de Andrade Jr.Director, Institute of Space Commerce, Austin, Texas, USA The Peoples Republic of China (PRC) is scheduled to complete its first space station in the next two years. With its Tiangong, Chinese Space Station (CSS), China has also raised many questions on how its capabilities are comparable and competitive with the International Space Station (ISS) also due to be decommissioned by 2024. The space race is on, and the CSS is a landmark of independent human flight capability that is just the beginning for China.  Photo:CMSA Photo:CMSA In the past ten years of research and development of space technology, China has enjoyed various opportunities to be a superpower in outer space. Steady economic growth rate and increase of its GPD enabling government funding are some of them. It has also developed its own national space technology with spacecraft launching capabilities, and its space activities are in accordance with the current international legal framework. On October 16, 2021, three Chinese Astronauts in the Shenzhou mission entered the Tiangong for a six month stay, its longest mission in history. China has launched 12 spacecraft, plus the Tiangong 1, and the Tiangong 2 Space Laboratory. The country has trained and sent 11 astronauts to outer space 14 times and returned them safely to Earth. The design life expectancy of the 5-module station is 10 years with possibility of extension. Prof. K. Ganapathy MCh (Neurosurgery), FACS, FICS, FAMS, PhDDirector Apollo Telemedicine Networking Foundation; Director, Apollo Tele Health Services; Past President, Telemedicine Society of India; Past President, Indian Society for Stereotactic & Functional Neurosurgery; Former Secretary/Past President Neurological Society of India;  I wish to thank Dr Thais Russomano for sharing with the InnovaSpace readers my article on “ Technology in Telehealth”, published in the IEEE Computer Society Region 10 newsletter. Also acknowledged is permission given by H.R. Mohan, Editor & Portfolio Member, IEEE Computer Society. The original article was for Telehealth on Terra firma ! How relevant is providing TLC ( Tender Loving Care) when the patient is 600 km above the earth and, perhaps in the future, several hundred million kms away? With failure not being an option in such an environment, both the beneficiary and the health care provider are perhaps only interested in technology per se and rightly so. Is there still a place for virtually empathising and sympathising with a patient, far away from Earth? Should we compound the already complicated milieu by taking into account the extra terrestrial patient’s wants and desires? And should the family also be involved in the decision making process or should we just leave it to an AI enabled algorithm which gives more weightage to the Microgravity environment and takes into account the lack of precedents? A media release said it all “NASA to send humans to the moon once again, – but this time we will stay“. This will also be a forerunner to the manned mission to Mars. With over 600 individuals already having gone into space in the last 55 years and space tourism having just started, extra terrestrial healthcare is now a reality. Bringing Space, down to Earth is not a pun. Representing almost 1% of global economic activity, the multiplier effect and stimulus to health and economic growth is real. There is considerable similarity between probing the emptiness of Space on distant galaxies and getting into millimetre sized capillaries in the heart and brain of the unborn – to go “ where no Man has ever gone before”. Belonging to the BC ( Before Computers - I was the last group of neurosurgeons trained in India when computers were almost non existent in a hospital ! BC is not Before Covid) era, I am Jurassic Park material and old fashioned enough to hope the super sophisticated Flight Surgeon on Earth instructing the on-board robot what to do, would still spare a few minutes and discuss with the family on Earth, the options and its limitations and advantages. Of course, we're not sure yet whether an individual space tourist / astronaut could give an Advanced Medical Directive before he leaves the Earth on a customised Informed Consent form. These ethical issues can no longer be postponed. The future is ahead of schedule. The future is yesterday not tomorrow!

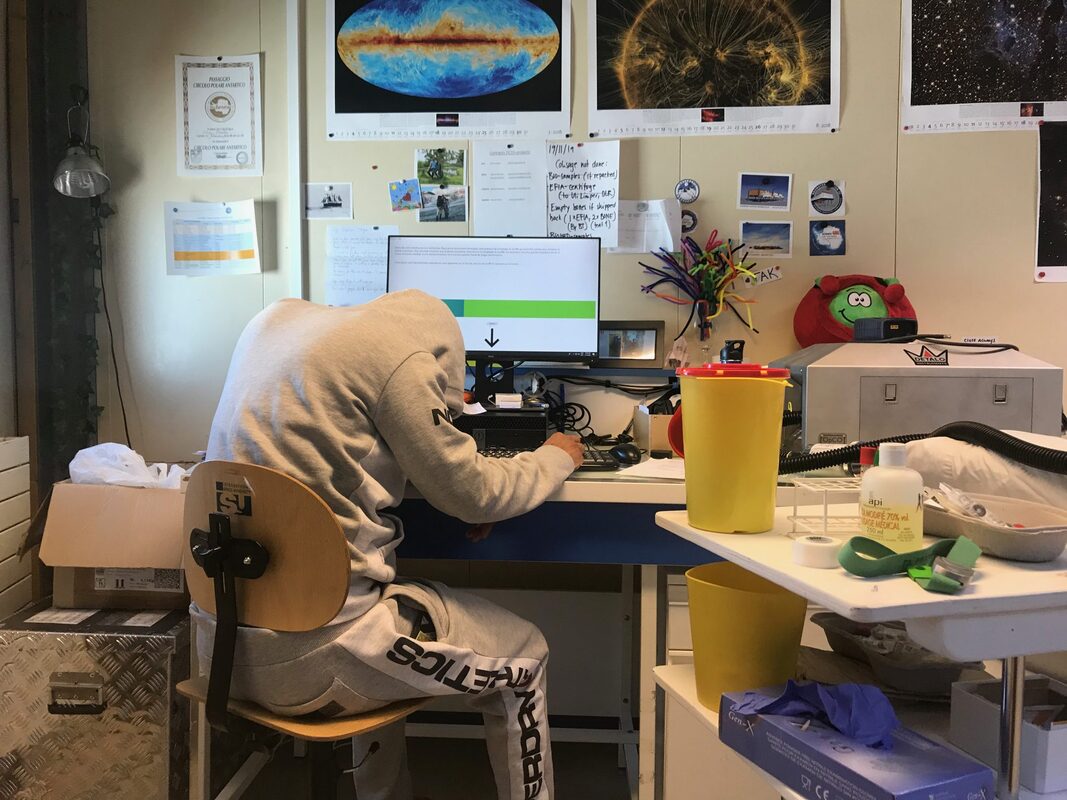

Final blog from ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen, from his series written while spending 12 months at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch up on the rest of his fascinating blogs by following the links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11, Part 12 Dr Stijn Thoolen Medical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica L’Astrolabe icebreaker, December 15, 2020 Sunlight: 24 hours a day, but tomorrow, as we head further north, it will set again Temperature: Around 0 °C Mood: not sure how to describe it today. I am excited and just feel very lucky. It’s midnight. Since our departure some hours ago the sun has steadily moved towards the horizon behind us, and it has started to paint the sky in colours that make me think of winter again. Huge icebergs are slowly passing by, and every once in a while there is a bunch of curious penguins waving us goodbye from their ice floe. Not much earlier I saw a seal chilling, and there have been whales too. In the very far distance I can still recognise the enormous ice mass on which we have been living our lives the past year. It’s my last view of the Antarctic, and it’s perfect. Standing here alone on the deck of the Astrolabe surrounded by all this beauty I have found myself a special opportunity to appreciate once more where the #$%!! (beep) we have been all this time. It is just so different there on top of the ice, so far away from the rest of the world, that as we are slowly being re-introduced to civilisation I am having a hard time believing it actually happened. With all the changes that we have gone through lately and with all the new impressions time has gone fast, and it has made Concordia feel like a distant, almost unrealistic memory. Like ages ago, even though it has only been eight days since we left… It started when the ‘orange and fat’ people (and kiwis!) arrived at Concordia about a month ago. With the start of the summer campaign our winterover isolation had come to an abrupt end, and I remember the calm, safe and familiar environment of the ESA lab feeling surprisingly pleasant after some intense hours of new social interactions. As a positive summer energy took hold of the station and fresh ESA MD Nick gradually took over the lab, there was no way for me to hide anymore. Unavoidable steps out of our rigid routines, but at that ‘c’est l’Antarctique’ rate of change that isn’t always easy to keep up with.

Our departure from Concordia last week was much the same. Emotionally numb from a lack of realisation of what was happening (or a lack of sleep the night before…) it just passed by so quickly, and surprisingly smooth. I said my goodbyes without any affection for the tears around me. I gave the station a good last look for the sake of memory. But when the plane started accelerating for lift-off, suddenly that strong desire came up to make it stop and bring me back safely into the station. Apparently part of me wasn’t ready to leave at all. Too big steps too quickly I guess, but lucky for me there were pilots taking care of that... A penultimate blog from ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen, from his series written while spending 12 months at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Enjoy the rest of his fascinating blog series by following the links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Concordia, November 29, 2020 Sunlight: 24 hours Windchill temperature: -45 °C Mood: positive, focused Today is Sunday. We are on full summer campaign steam for two weeks now. There are about 40 people occupying the station, but today nobody works. Instead, I am wearing three layers on my legs, five on my torso, two pairs of socks, neck warmer, two balaclavas, hat, goggles, glove liners, mittens, radio, and of course my running shoes. I prepared two-and-a-half litres of isotone sport drink and extra electrolyte tablets against the dry desert atmosphere. Extra goggles for when my visor fogs from sweat that cools off in the freeze. Battery-powered heated gloves, air-activated hand- and feet warmers as well as another pair of shoes for when my body becomes unable to pump sufficient blood to my fingers and toes to keep them warm. Bananas and chocolate bars accommodating high energy demands at this altitude and these temperatures. Spare radio battery to make sure I maintain contact with the station. Tape for whatever unforeseen circumstances, and four volunteers and a skidoo standing by to support me with whatever I request. Today I am going to run a marathon. I guess I can sometimes be a bit of a dreamer. Not necessarily in the sense that I tend to lose touch with the world around me in order to float around in some self-invented realm in a galaxy far, far away (no worries, I do that too sometimes), but I do like to fantasise about doing things that are commonly perceived as unachievable. Or at least to say a challenge. Then afterwards I see myself devoting quite some time towards realising (some of) such ideas, because it makes me feel good. Contradicting, right? Well, I have to admit I sometimes do find myself wondering why the … I got myself in an awkward position again, but overcoming a challenge in the end always makes me feel proud, and most importantly the experience that comes with it makes me learn.

As I have probably mentioned in all my previous blogs (hope I am not starting to bore you), I strongly believe that pushing yourself into an unknown (decide for yourself how) and leaving your comfortable space can broaden your horizon. We can allow ourselves to understand the world around us from new perspectives, and see new ways of tackling the difficulties that life will offer us. In that sense, I guess it can make us more resilient. Isn’t that exciting? It is this curiosity that made me come to Antarctica in the first place, and enjoy the winterover experience that is often said to bring positive psychological impact to those who are able to overcome the challenge of being far from home in isolation and confinement. As ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen comes closer to the end of his year at the Concordia research station in Antarctica, he begins to reflect on his experiences of the last year and the journey homewards. Enjoy the rest of his fascinating blog series by following the links: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Concordia, October 4, 2020 Sunlight: about 14 hours per day Windchill temperature: -85 °C Mood: excited, but there is a pinch of nostalgia. Already… It’s 1:00 AM. I am lying outside on the roof, together with Ines (glaciologist), Elisa (cook) and Andrea (vehicle mechanic). There is a full moon shining on us, and Mars is right next to it. I am not much of an astronomer, but its bright color stands out so clearly from all the other celestial objects that even I can recognize it instantly as the Red Planet. Looking to the southwest I see Jupiter and Saturn. Also pretty hard to miss. Usually that is where I find the Milky Way, but there is too much light now, even at this hour. An amber color brightens the horizon, beyond which I now realize again there are just so many miles of ice (something easily taken for granted here, but thinking back to that inbound flight to Concordia last year does the trick) separating us from the rest of the world. In front of it all, I look at the frosty metal bars, which always looked so surrealistic to me when I saw pictures of them back home. They have gone through winter as well…

The return of the sun was cool. ‘Here comes the sun’ (you know, that one from the Beatles) was heard all over the station while we impatiently and excitedly tried to catch a first glimpse of it mid-August. Since that moment the skies have become more and more blue, and the snow more and more bright. I have experienced the gradual return of daylight over the past weeks with a positive and fresh feeling, and a sense of anticipation has started to take hold of the station. Who are the people who will replace us? What are our plans after Concordia? I remember myself some weeks ago, lying in exactly the same position as I am right now, outside against a snow dune, sheltered from the wind and with a pleasant -50 degrees Celsius (I realize this perception must be taken relatively…), alone, and just letting the sunshine touch my face again. A special moment, that reminded me of how pleasant summer conditions are going to be.

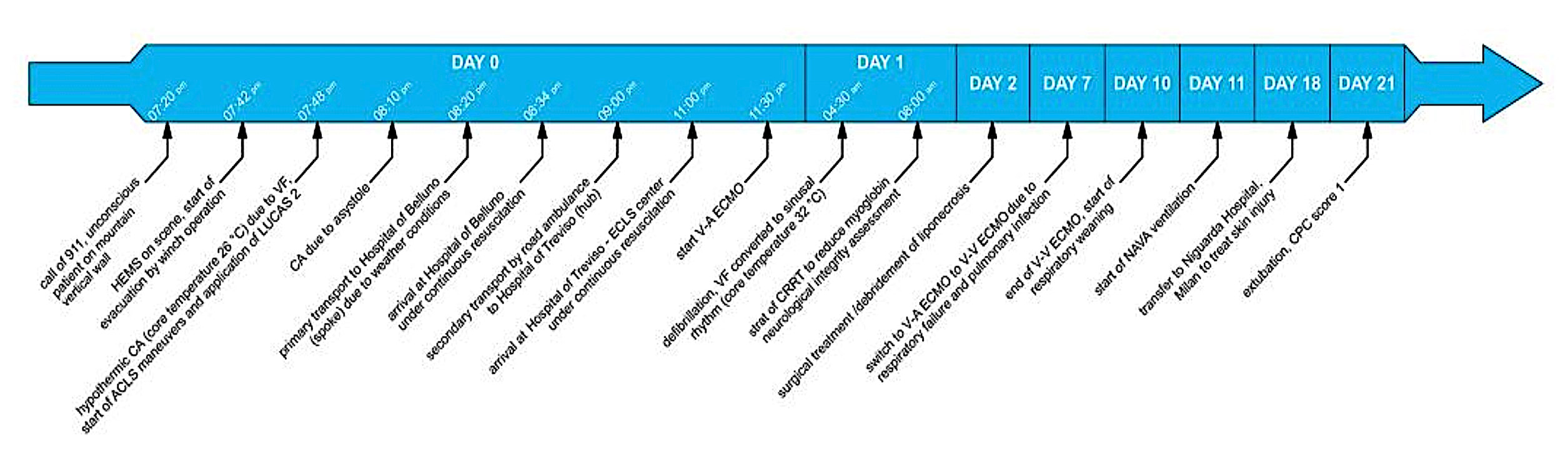

We welcome back helicopter flight physician Dr Alessandro Forti, as he recounts the true story of an incredible mountain rescue in the Dolomites. We never truly know when we wake up each morning if this could be our last day of life - we assume that all will be well - as did a keen mountaineer in Italy, whose life unexpectedly hung in the balance and in the responsible hands of a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service team with a Lucas device! Do also take a look at Alessandro's previous blog, which began his dream to work in the rescue services. We describe here a case of full neurologic recovery from accidental hypothermia with cardiac arrest, which involved the longest reported duration of mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and extracorporeal life support (8 hours, 42 minutes). A 31-year-old man experienced a witnessed hypothermic cardiac arrest with a core temperature of 26C° (78.8F) during a summer thunderstorm on the vertical wall of the Marmolada mountain in the Dolomites, Italy (Figure 1), in the late afternoon on a summer day (day 0). The trapped climber was secured on the wall without any form of waterproof clothing and reportedly had already lost consciousness in the few minutes it took his companion to reach him. The companion signalled for help, using a light on his smartphone device directed toward a nearby mountain hut. The local helicopter emergency medical system was called (7:20 PM) (Figure 2).  FIGURE 2: Course of treatment. HEMS, hospital emergency medical system; CA, cardiac arrest; VF, ventricular fibrillation; ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ECLS, extracorporeal life support; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; NAVA, neurally adjusted ventilator assist; CPC, cerebral performance category  LUCAS 3 system maintaining chest compressions LUCAS 3 system maintaining chest compressions A physician-staffed helicopter reached the scene at 7:42 PM, and the unconscious patient was immediately evacuated with a 30-m winch operation. The helicopter landed nearby; the initial cardiac rhythm was a low-voltage ventricular fibrillation (7:48 PM). Resuscitation manoeuvres started immediately with manual CPR, followed after a few seconds by an electrical shock (200 J biphasic); mechanical CPR was started after one complete cycle of manual resuscitation. CPR was continued with a mechanical chest compression device (LUCAS 3; Physio Control, Redmond, WA); initial end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) level ranged between 14 and 22 mm Hg. At 8:20 PM, the patient was transferred by helicopter under continuous mechanical CPR to the spoke Hospital of Belluno, Italy (43 km; arrival at 8:34 PM), as a direct flight to the hub Hospital of Treviso, Italy, was impossible because of the darkness. On arrival, the patient’s core temperature was stable (26.6C° [79.9F]) and cardiac output under continuous CPR was considered sufficient (ETCO2 22 mm Hg); therefore, in accordance with the local protocol for refractory hypothermic cardiac arrest, the patient was transferred to a road ambulance and transported to the hub hospital (Treviso, Italy; 83 km) under ongoing mechanical CPR; meanwhile, the extracorporeal life support team was alerted. After the patient’s arrival (11 PM), venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was commenced (11:30 PM). Core temperature (esophageal) was 26.1C°. On day 10, there was a partial recovery of the ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction 40%) and ECMO was removed. On day 21, the patient was extubated; cerebral performance category score was 1, with only mild retrograde amnesia at day 28. Three months and 10 days after the accident, the patient left the rehabilitation unit and resumed normal daily life activities, with only minimal impairment of short-term verbal memory. After one year the patient and the companion return to the place of the accident and with an US film factory and Stryker filmed a documentary about this event. ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen delivers the last part of his 'Let's Talk Science' blogs, written during his year at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica But there is more to the ESA lab, and I have saved the best for last. So, now that you are probably overloaded with theories and facts, let’s talk about something very different. Let’s talk about sex! And before we continue, you have to promise me to turn on another song, to end this blog with some appropriate groove.

But maybe there is more to it than it seems, and what Cherry-Garrard says is not necessarily easy to do. We are human, after all. Sexuality is one of our core features, vital for our existence, and for many it is a fundamental source of pleasure, intimacy, bonding, and social relations. Researchers have shown how sexual deprivation can lead to frustration, anger and even depression, and also seen from a group perspective anecdotal accounts have shown that sexual desire and related feelings of jealousy and competition can lead to adaptation problems in extreme environments. Including Concordia! But the problem with sex it that we don’t easily talk about it. Perhaps it is so close to our core that opening up about it can make us feel vulnerable. A sensitive topic, and while researchers are currently busy figuring out how to compose future space crews in terms of culture, personality and gender, data about sexual behaviour and its effects on team dynamics in extreme environments is basically non-existent! How do we cope? How, why, and when do we suffer? Recent political debates and scandals of sexual harassment have already highlighted the importance of having a work environment free of sexual hostility, and if you ask me, it would be irresponsible to send humans on a multi-billion dollar long-duration mission to Mars without being able to answer these questions! As such, the project SWICE (‘sexual well-being and sexual security in isolated, confined and extreme environments’), for the first time in spaceflight research history, is breaking the taboo. As the first study of its kind, it aims to gather basic information about human sexuality while living in isolation and confinement, and it does so by making us in Concordia talk:

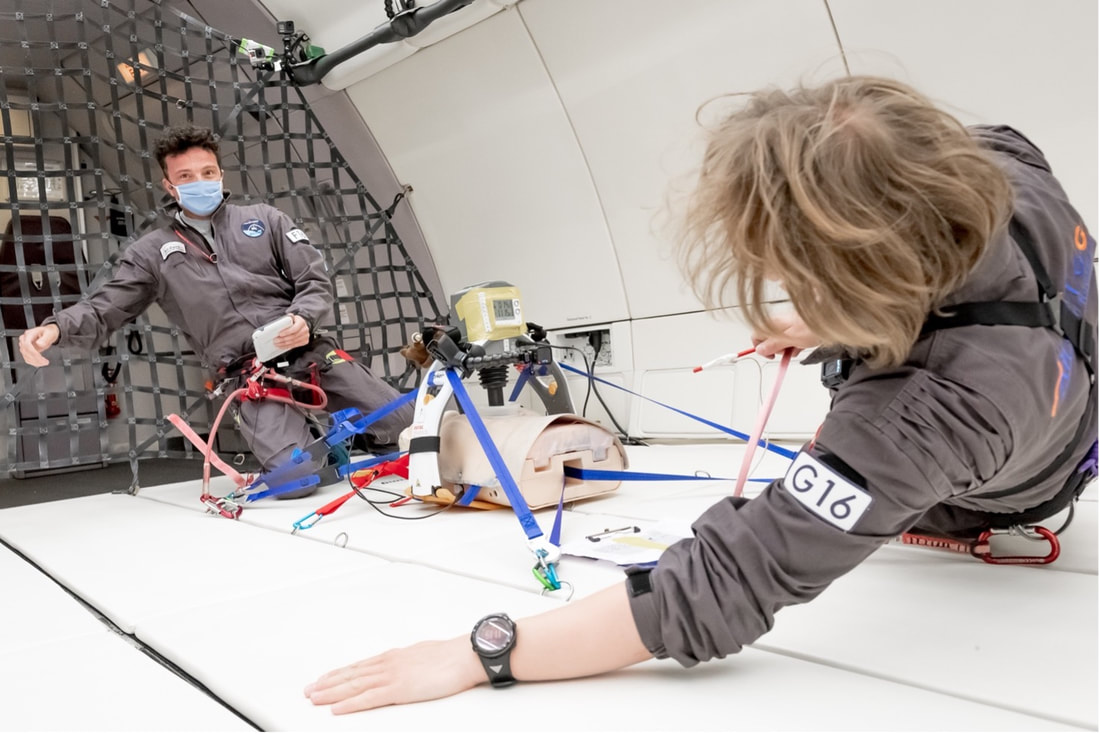

‘How often does another Concordia inhabitant asks me for sexual favours?’ (we better forget the jokes at the dinner table…), ‘How often does another Concordia inhabitant produces sexually explicit graffiti for display at Concordia?’ (we better forget the sexually explicit Play-Doh creations we made with the whole crew last month…), ‘How enjoyable is your sexual life right now?’, ‘How often do you masturbate?’, ‘How often do you experience an orgasm?’ (Damn, you want to know everything!).  Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons Image: The Dolomites, David Millett, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons If someone asked you – “what do you want to do when you become an adult?" – what would your response be? Now, imagine me as a 14-year-old student at an art school, and one day going to a Red Cross course and recognizing that you love the idea of the First Rescue and Emergency services. My first answer was always – Astronaut! But… what should I do now? Astronaut or Doctor ...? Solution? Helicopter flight physician! But how can I do this thing…is it possible? Yes, it is! I first studied medicine and became an anesthetist and intensivist. And so it was… once I graduated and then specialized in anesthesia, I began to frequent the world of Helicopter Rescue. A fantastic job that combines flight, wonderful landscapes (the Dolomites ...) and the human factor. A lot of different situations every day and in different places. The helicopter flight physician is responsible for providing casualties with emergency medical assistance at the accident site, as well as attending to patients during primary and secondary missions. The scope of activities also involves recovering patients from topographically difficult terrain by means of a rescue hoist. This applies exactly from the time the patient is put into your care until you hand them over to the medical staff responsible at the destination hospital.  LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions LUCAS-3 (Stryker) - delivers high-quality consistent chest compressions I remember one early afternoon in September 2013, the Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) Dispatching Centre of Treviso, Italy received a call from a person who told the operator that her cousin, a 53-year-old man with a previous history of inferior myocardial infarction, had suddenly fallen down while walking at home. While dispatching the nearest ambulance, the dispatcher provided CPR pre-arrival instructions to the caller, according to standard protocols. An EMS helicopter, staffed by an emergency physician (namely, me!) and a nurse, was dispatched to the scene. The first emergency unit, staffed by a nurse and an emergency technician, reached the patient within 10 minutes of the call and found the woman performing chest compressions as instructed by the dispatching center operator. My team in the helicopter reached the patient 10 minutes after the first unit started ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support). The cardiac rhythm was a persistent ventricular fibrillation and the decision was made to apply a LUCAS-3 chest compressions device to the patient, who was then transported directly to the hospital and catheterization laboratory. Selective percutaneous coronary angiography was performed with ongoing continuous mechanical chest compressions. Coronary angioplasty was performed on two coronary arteries. Five days after resuscitation, the patient was extubated and was alert and oriented. After 16 days he was discharged from the Intensive Care Unit and transferred to a post-intensive care unit. The patient survived without any neurological damage despite prolonged resuscitation and a call-to-ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation) interval of nearly 2 hours. The immediate beginning of chest compressions by the caller and uninterrupted CPR by medical teams preserved the brain from ischemic damage. The mechanical chest compression device permitted safe and effective CPR during helicopter transportation directly to the catheterization laboratory, which permitted the removal of the coronary artery occlusions, which were preventing the ROSC. This is why I think this is an amazing job… A little about the author: Alessandro Forti As well as being a certified specialist in Cardiac-Anaesthetics, Intensive Care Medicine and Aerospace Medicine, currently working as an intensivist, cardiac-anesthesiologist and HEMS doctor in northern Italy, Alessandro has a passion for space clinical medicine, which began in 2012 following a post-graduate course in Space Medicine at the San Donato Milanese University. He has been involved in space medical research as a COSPAR (Committee on Space Research) collaborator and acted as a reviewer of many scientific articles for the journal Advances in Space Research (Elsevier). He was also Coordinator of the HEMS base in Pieve di Cadore-Italy from 2018-2020. Alessandro is Principal Investigator for the research Mechanical Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Simulated Microgravity and Hypergravity Conditions: a manikin study, which took place during the 4th. parabolic flight campaign in Dübendorf (CH) in June 2020, in collaboration with the SkyLab Foundation, CNES and DLR. His main areas of interest are space clinical medicine, CPR in different environments (mountain, avalanche victims, hypothermia, hyper and microgravity), ongoing CPR with ECMO (Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation) neuroprotection and neuromonitoring during DHCA (Deep Hypothermia Cardiac Arrest) in Cardiac Surgery.

We continue to follow along with the wonderful experience of ESA-sponsored Dr Stijn Thoolen during his year spent at the Concordia research station in Antarctica. Catch-up with his previous blogs at Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8 Dr Stijn ThoolenMedical Research Doctor, Concordia Research Station, Antarctica Fortunately it is not all body fluids (and solids) in the ESA lab. Other projects are more interested in the psychological adaptation to space-like environments. How do we deal mentally with the isolation far from home, the confinement, monotony, and life in a small international crew? The experiences and stressors that crews face during such missions require a certain degree of mental resilience, or may otherwise result in cognitive or behavioural problems and a loss of performance that can be dangerous to both the crew and the mission. To facilitate such psychological adaptation and resilience, the scientists behind MINDFULICE (‘role of mindfulness disposition in an isolated and confined environment’) for example are investigating the use of ‘mindfulness’ as a tool for deep space missions. ‘But isn’t that something for Buddhist monks?’, I hear you question… I actually like to think it is quite the opposite. And although maybe it isn’t an easy construct to grasp, we are all already mindful to a certain degree. Perhaps it is best to think of it as a mental process, of being aware in the present moment, welcoming what is new with an intention of kindness and compassion, and being open-minded enough to see new possibilities in any given situation rather than relying on what you have previously learned. Everyone does that to a certain degree, but everyone can also learn to do it more. Perhaps that is the biggest reason that the concept is gaining so much popularity so quickly. In our stressful and busy lives, mindfulness helps us to see solutions rather than problems, and research has already demonstrated many of its benefits, spanning from health and well-being to even business and artistic endeavours! A mindful attitude has shown to reduce stress while increasing resilience, task performance, enjoyment, psychological and even physical well-being, and in general a higher quality of life. That, I would say, is the promising power of the mind! So can mindfulness also help astronauts to cope with the harshness of a deep space mission? We like to think so, but to find out we must first understand how it relates to stress and psychological wellbeing in such conditions, and Concordia serves as the ideal testing ground. Of course that means more tests for us, so over the year we fill in questionnaires and perform attention tasks to determine how mind- and stressful we actually are. And how about you? Are you mindful enough to one day float to the stars? Note: this article was originally posted on the ESA blog website (LINK) and permission has been obtained to republish it here.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed