|

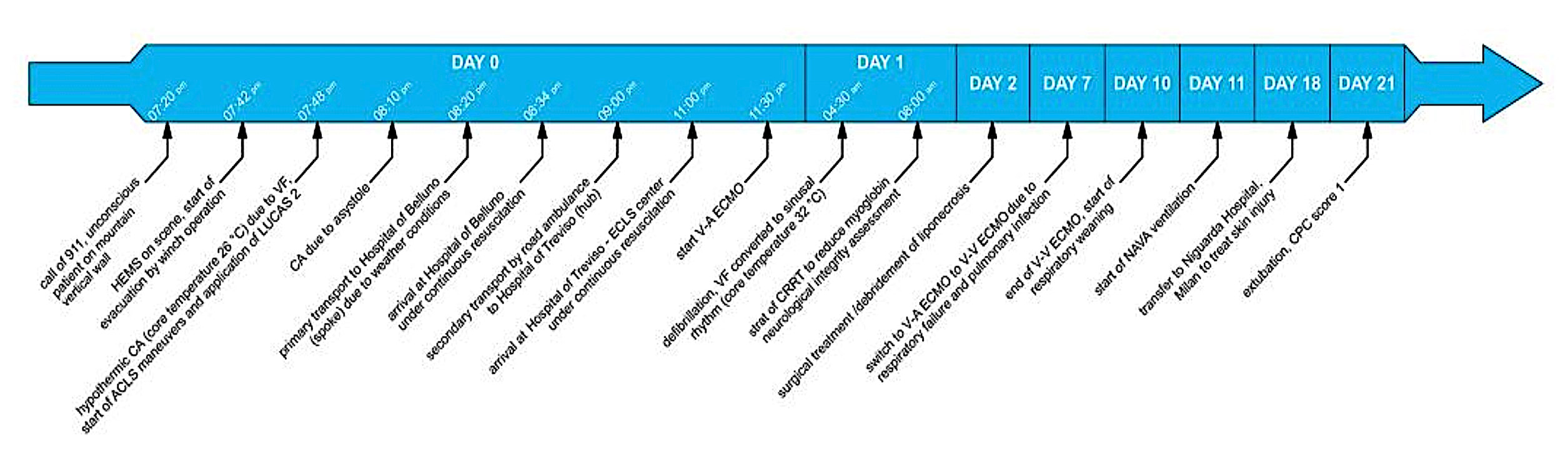

We welcome back helicopter flight physician Dr Alessandro Forti, as he recounts the true story of an incredible mountain rescue in the Dolomites. We never truly know when we wake up each morning if this could be our last day of life - we assume that all will be well - as did a keen mountaineer in Italy, whose life unexpectedly hung in the balance and in the responsible hands of a Helicopter Emergency Medical Service team with a Lucas device! Do also take a look at Alessandro's previous blog, which began his dream to work in the rescue services. We describe here a case of full neurologic recovery from accidental hypothermia with cardiac arrest, which involved the longest reported duration of mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and extracorporeal life support (8 hours, 42 minutes). A 31-year-old man experienced a witnessed hypothermic cardiac arrest with a core temperature of 26C° (78.8F) during a summer thunderstorm on the vertical wall of the Marmolada mountain in the Dolomites, Italy (Figure 1), in the late afternoon on a summer day (day 0). The trapped climber was secured on the wall without any form of waterproof clothing and reportedly had already lost consciousness in the few minutes it took his companion to reach him. The companion signalled for help, using a light on his smartphone device directed toward a nearby mountain hut. The local helicopter emergency medical system was called (7:20 PM) (Figure 2).  FIGURE 2: Course of treatment. HEMS, hospital emergency medical system; CA, cardiac arrest; VF, ventricular fibrillation; ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ECLS, extracorporeal life support; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; NAVA, neurally adjusted ventilator assist; CPC, cerebral performance category  LUCAS 3 system maintaining chest compressions LUCAS 3 system maintaining chest compressions A physician-staffed helicopter reached the scene at 7:42 PM, and the unconscious patient was immediately evacuated with a 30-m winch operation. The helicopter landed nearby; the initial cardiac rhythm was a low-voltage ventricular fibrillation (7:48 PM). Resuscitation manoeuvres started immediately with manual CPR, followed after a few seconds by an electrical shock (200 J biphasic); mechanical CPR was started after one complete cycle of manual resuscitation. CPR was continued with a mechanical chest compression device (LUCAS 3; Physio Control, Redmond, WA); initial end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) level ranged between 14 and 22 mm Hg. At 8:20 PM, the patient was transferred by helicopter under continuous mechanical CPR to the spoke Hospital of Belluno, Italy (43 km; arrival at 8:34 PM), as a direct flight to the hub Hospital of Treviso, Italy, was impossible because of the darkness. On arrival, the patient’s core temperature was stable (26.6C° [79.9F]) and cardiac output under continuous CPR was considered sufficient (ETCO2 22 mm Hg); therefore, in accordance with the local protocol for refractory hypothermic cardiac arrest, the patient was transferred to a road ambulance and transported to the hub hospital (Treviso, Italy; 83 km) under ongoing mechanical CPR; meanwhile, the extracorporeal life support team was alerted. After the patient’s arrival (11 PM), venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) was commenced (11:30 PM). Core temperature (esophageal) was 26.1C°. On day 10, there was a partial recovery of the ventricular function (left ventricular ejection fraction 40%) and ECMO was removed. On day 21, the patient was extubated; cerebral performance category score was 1, with only mild retrograde amnesia at day 28. Three months and 10 days after the accident, the patient left the rehabilitation unit and resumed normal daily life activities, with only minimal impairment of short-term verbal memory. After one year the patient and the companion return to the place of the accident and with an US film factory and Stryker filmed a documentary about this event. Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

InnovaSpace Ltd - Registered in England & Wales - No. 11323249

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed