|

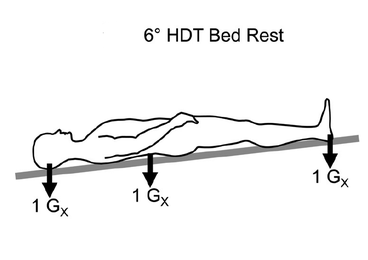

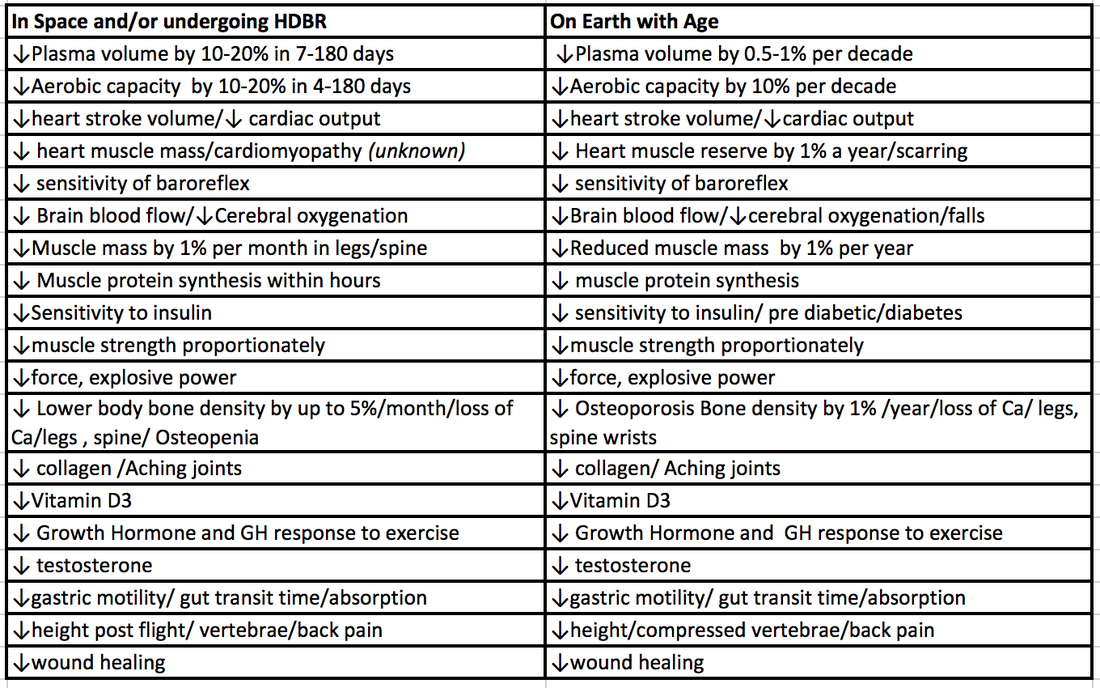

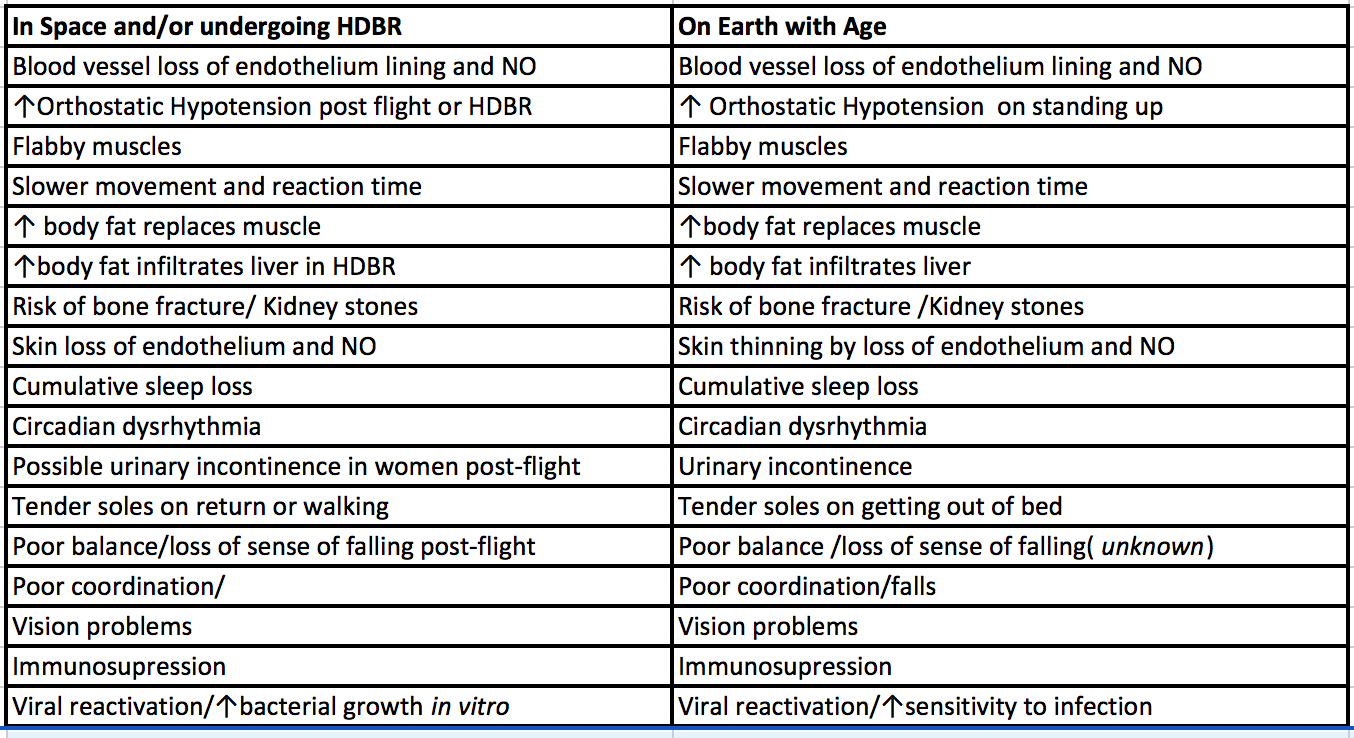

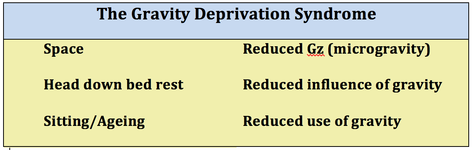

Blog written by Joan Vernikos PhD, Thirdage llc, Culpeper VA, USA  While teaching Pharmacology at Ohio State University (OSU), I was lured to NASA Ames Research Center in 1964 by Dr.Eric Ogden, the Chair in Physiology at OSU and a cardiovascular physiologist, to join him in a small unit of five research scientists. My background had been in brain/stress regulation; there was also a microbiologist, an exercise physiologist, a metabolism and a biological rhythm scientist. Very little was known about what happens to humans in space; our observations from one flight to the next slowly enabled us to form a picture of what might be happening, but progress was gradual. We had to find a way to at least simulate the effects of space flight on the ground and facilitate research that would complement and help us understand what the consequences of living in the microgravity of space might be.  Image from article by Hargens & Vico Published 15/04/2016 DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00935.2015 Image from article by Hargens & Vico Published 15/04/2016 DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00935.2015 Eventually, the optimal model adopted by the space science research community as a means for studying the physiological changes occurring in weightlessness during spaceflight was 6˚ Head Down Bed Rest (HDBR) or variations of this. In essence, by lying down continuously, the maximum influence of the force of gravity pulling down on us, Gz (head-to-toe), is minimised to Gx (across the chest). It was from such studies in healthy volunteers that I first noticed the similarity in changes seen in astronauts in space to those of people ageing on Earth. Muscle and bone wasting, reduced blood volume, a type of anemia, fluid and electrolyte shifts, cardiovascular deficits, and reduced aerobic capacity alterations in space all resulted on return to Earth in the astronauts experiencing fainting, and disturbed balance and coordination. These changes are also known to be the underlying causes of falls in the elderly. However, this conclusion was met with disbelief, including my own, since healthy young astronauts and HDBR volunteers recovered soon after returning to Earth or on becoming ambulatory. As knowledge accumulated and the duration of space missions grew longer, it has become clear that both the physiological response to spending time in space, as well as the ageing process on Earth, are gravity-dependent conditions.

<

>

Recovery from 6-month stays in space confirm that recovery is difficult, slower or impossible. Though bone density, for instance, may recover its density, its architecture is more like that of an older person and not likely to recover. The rate of change of bone in space is also faster than found on Earth, with around 1% loss of bone density a year on Earth, whereas in space this loss is more like 1% a week or month. On Earth, gravity has been considered the enemy that drags us down and ages us. But the reverse is true. From birth, from the buoyancy of the womb through peak development, children intuitively learn from the beginning to use gravity in the design and function of their body. They do this by moving and orienting themselves in as many ways as possible, exposing all parts of their body to this universal stimulus. Skeletal, neuro-muscular and cardiovascular stimuli are below threshold in the microgravity of space, which results in a 10-times faster onset of atrophy. On return to Earth functional capacity is equally reduced 10-times faster than in ageing. There are comparable underlying metabolic and morphological disturbances where decreased mechano-transduction is a common factor. As more advances are emerging from the science of ageing, such as the discovery of telomeres, it has become possible to compare these with those in space. Though gravity is ever-present on Earth, it is useless if we do not use it. Deconditioning in space from gravity deprivation, and reduced gravity influence in bed rest, have drawn attention to the medical hazards of gravity withdrawal in other gravity-related conditions, such as sedentary office work and other ageing lifestyles. Today’s prolonged hours of uninterrupted sitting in both these cases have been linked to atrophic, inflammatory and metabolic conditions, from cancer, diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular changes and ageing. The answer simply lies in relearning to use gravity, much as a child does when playing – moving from dawn to dusk, incorporating multiple changes in posture with intermittent, low intensity, high frequency movement. Gravity clearly plays a role from cradle to grave. Understanding that role may, in fact, provide sought-after simple and inexpensive solutions to a broad variety of today’s common disorders, all the way to achieving greater independence and longevity.

"The body electric" as Walt Whitman eloquently described the human physique in the full flush of health almost 100 years ago (Forbes, April 2, 1921) "is attainable by all. It is a matter of living sanely, according to the dictates of common sense."

Stein E. Kravik

30/9/2017 10:35:21 pm

Dr. Joan Vernikos worked at NASA'a Ames Research in 1980-s when I was doing research for my PhD. Using water immersion to simulate the effects of weightlessness (the other major model to simulate weightless as compared to HDBR described by Joan). Her observations on gravity and aging cannot be emphasized strongly enough. Not only does our use of gravity delay aging. It keeps you in good health, both mentally and physically. In other words this is preventive medicine at it best! Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed