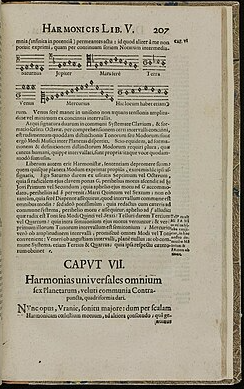

Author: Luis E. Luque Álvarez Violin Teacher, Kittenberger Kálmán Primary & Art School of Nagymaros, Hungary. Member of the European Low Gravity Research Association (ELGRA), and member of the Education Advisory Board for NASA’s Eclipse Soundscapes Project (ES: CSP) Are the right polyphonies of orbits contributing to the rise of life in the universe? Sonification is a multidisciplinary method that complements data visualisation through adding an auditory component that facilitates the interpretation of visual features. The origin of sonification dates to 1908, when Hans Geiger and Walther Müller experimented with the sound coming from tubes of ionizing gas and radiation. Edmund Edward Fournier d’Albe later invented the Optophone, a device that scans text and transforms it into time-varying chords of tones, enabling people who are blind to identify and understand letters through sonification. This method has become popular in astronomy, though its real roots can be traced back further in history if you consider the works of Pythagoras, who proposed that planets all give off a unique hum based on their orbital revolution, while the “Musica Universalis” developed by Johannes Keppler highlighted the orbital path of each celestial body as individual voices in a planetary polyphony. Andreas Werckmeister subsequently developed his temperaments and tuning systems based on Kepler’s theories, which later influenced the sequences and structures composed by Johann Sebastian Bach. This connection from Kepler to Bach continues to be investigated to the present day by musicologists. In fact, in can be argued that without the musical developments of Pythagoras, Kepler, Werckmeister and Bach taken from astronomical principles, the musical systems and knowledge of our postmodern times could be very differently structured, at least considering western music. Astronomical studies seek the combination of different celestial harmonies or polyphonies from the orbits that could have a direct relation with the essential conditions for life in evolving protoplanetary systems, different stars, planets transformation or even the connection to black holes or dark matter (see below YouTube videos). Sonification is also a highly multidisciplinary field, in which artists, educators, science communicators and scientists intersect and collaborate. This has sometimes created difficulties in community efforts to define sonification and demarcate artistic and scientific boundaries.

Astronomical Sonification One of the first modern astronomical sonification works seen used data collected by the Voyager spacecrafts in the late 1970’s, when Jupiter’s magnetosphere was transferred into sounding spectrograms containing gliding frequencies, with some already identifiable notes and patterns. In 2021 composer Vangelis released the album Juno to Jupiter, also containing recorded sonification transmitted by the Juno space probe in orbit around Jupiter, similarly to the Voyager spectrograms. Over the last two decades astronomical data translation to sound has become a frequent practice, using images taken by the Hubble and Chandra space observatories. Sonification has relevance though not just for listening to the distant universe but also for Earth observation, such as the wind data translation to music from the European Space Agency Aeolus mission in collaboration with composer Jamie Perera, who interpreted the Rayleigh parameters of different winds using the Greek Lydian Mode and instrumented for woodwinds and ambient synth. Antonio Vivaldi couldn’t access such data when he wrote the magnificent Four Seasons in the 18th century, but perhaps this may inspire new sonification ideas and musical compositions derived from Earth Observation data based on nature’s behaviour.

All the light we cannot see…but to which we can listen! The NASA funded Eclipse Soundscapes project extends to citizens the possibility of making multisensory observations focused on collecting audio data from wildlife behaviour before, during and after the occurrence of different types of solar eclipse. This opens new frontiers and the possibility for blind and low-vision communities to experience such events closer than ever, whilst also providing scientists with the soundscape data from different locations and showing how solar eclipses can affect life on planet Earth. Light is energy and as with many astronomical images, eclipses represent a massive decrease and increase of energy that eventually varies the rhythmic, melodic and polyphonic structure of nature. The rise of telescopes like Webb, Euclid and Chandra has led to increased sharpness of the data available, positively stimulating the number of music composers interested in interpreting the images’ light into their own tangible musical. NASA’s Universe Sound project focuses on X-ray visible and infrared light. The approach of composer Sophie Kastner uses not the whole image but rather focuses on small sections of the original images from Chandra, Hubble, and Spitzer, with which she composed the work “Where Parallel Lines Converge”, instrumented for a contemporary ensemble and having an interesting light intensity musical approach. Maybe one day space crews will be able to interpret the data coming from what they see, analyse it at the exploration site, send it back to Earth in sonification format, or even compose or play music from it. Perhaps it’s just a question of who will be most enthused and find it an enjoyable experience? Music composition involving astronomical events is extremely important for visualising, interpreting, imagining and drawing concepts of the story of the light we cannot see with the naked eye, and it serves to make astronomy more inclusive and bring it to a non-scientific society. Bring music to commercial spaceflight but not commercial music to spaceflight! Since the 1960s, space crews have been meticulous in their music selection and choice of musical instruments to take into space, all carried out under strict payload limitations. Playing musical instruments can positively support astronaut mental health as a psychological countermeasure against the noisy environment of space vehicles, the monotony of long-term confinement, and lack of Earth-like artifacts. Equally, the potential effects that musical content and performance may have on physiology in microgravity conditions are unknown, for example posture when playing an instrument. Astronaut Christina H. Koch (crew member for Artemis II) mentioned after practicing a favourite song on the ISS Yamaha keyboard that some of the melodies stayed with her on repeat in her head, positively boosting a complete EVA spacewalk the next day. Musical instruments were not carried on flights during the Apollo programme, with some astronauts reporting being irritated by the music choices of their fellow crewmates; restrictions on the number of cassette tapes that could be flown probably led to frequent repeats! Contemporary postmodernism music practice is becoming more linked to astronomical sonification, however, when considering human psychophysiological wellbeing, no matter what the musical genre, the implementation of traditional, coherent, organised musical forms & structures still dominates, providing more interest and wellbeing to wider communities for longer periods of time. Musical tastes change over the decades and centuries, with the compositions of some composers and artists remembered and actively listened to, while others are forgotten or lose relevance as the commercial interests of the music industry evolve. Nonetheless, when it comes to space missions, rockets are never loaded with the wrong propellant or fuel, and the case for music in spaceflight is just as relevant. Music has been and will continue to be a necessary commodity to support the positive wellbeing of future space travellers worthily and musically. Interested in sonification and music to rock the universe?

Take a look at this fantastic resource: NASA's Space Jam and use code to create a solar system that rocks! Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed