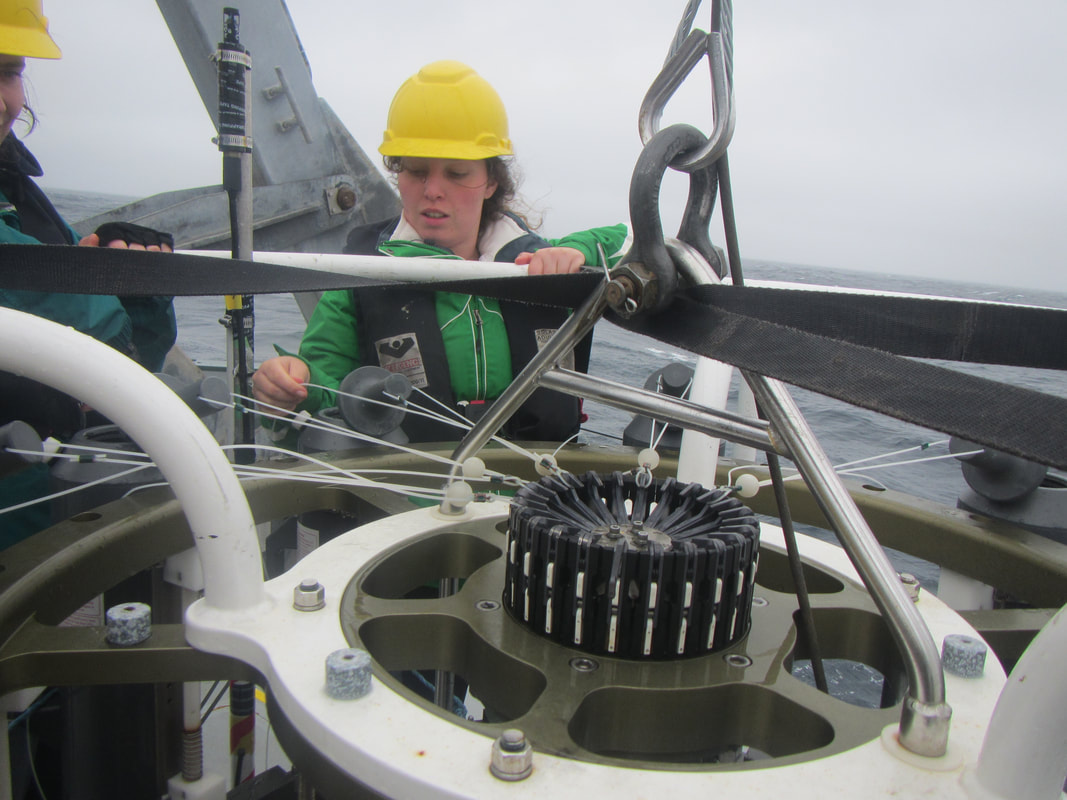

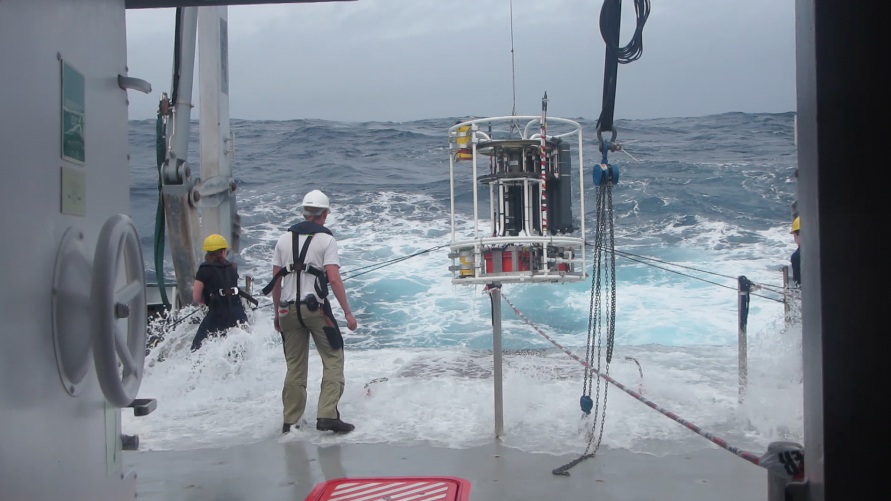

Dr. Gabriela S. PiloOceanographer, Institute for Marine & Antarctic Studies (University of Tasmania, Australia)  Oceanographer, Dr. Gabriela S. Pilo Oceanographer, Dr. Gabriela S. Pilo It is quite easy to draw a parallel between ocean and space exploration. Both require a ship, a large sense of adventure, and a love of discovery. But there are more similarities between the ocean and space than simply their ability to feed the imagination of writers, musicians, and curious minds. The ocean, like space, is still unknown. Similarly to space research, ocean researchers are still trying to fill several knowledge gaps. We’ve advanced a lot since the beginning of modern Oceanography, attributed to the Challenger Expedition in 1872. We have now charted the main ocean currents, from the surface down to the bottom of the ocean, at 6000 m depths. We understand how and where surface waters become dense and sink, creating a conveyor belt that connects the whole planet, travelling for 1000 years before re-surfacing. We also understand that ocean currents interact with the wind, the ocean floor, and with each other, and break into several rotating bodies of water, known as ocean eddies. These eddies spin away, carrying their parent current’s water to distant parts of the ocean. However, as in space, there is still a lot we don’t know. Gaps in ocean research relate to balances of energy and of biogeochemical compounds, and to the response of the ocean to a changing climate. Considering that there still so much to learn, we often find ourselves in the middle of the ocean looking for answers. This brings up the second similarity between ocean and space research: when you are out there, conditions can get harsh! Open-ocean Oceanographic cruises can last for up to 3 months, having only a few shore stops during this time. Therefore, like in space, an oceanographic vessel must be autonomous for a long period of time. During research cruises, scientists and crew members are putting all their efforts into sampling the water and measuring physical properties of the ocean. Sampling happens under all circumstances, in the middle of the night, in rain, snow, and under very high wave conditions. In addition, icebreaker vessels can go deep into an ice field, and reach the most remote parts of the world. Ocean-sickness, just like space-sickness, often kicks in, as your body gets used to the constant movement. You are also living in a confined space with like-minded people that have one goal: to do science. But the ocean is not just a large body of water, flowing and crashing against the shore. The bathymetry of the ocean, the chemical elements dissolved in the water, and the animals, microbes, and algae that live in it, are equally important and fascinating. Oceanography is a highly multidisciplinary research field. Therefore, to fully understand the ocean, we need to collaborate. It takes a team of physical oceanographers, marine biologists, geologists, meteorologists, glaciologists, and several other scientists to put the pieces of the puzzle together. This team work builds up our knowledge of the ocean. Just like in the space sciences, collaboration is key! For example, the InnovaSpace Team is composed of experts in life science, telehealth, and engineering. Finally, the ocean, like space, is vast. We cannot be everywhere, at all times to study it. To obtain global, constant measurements of the ocean we rely on state-of-the-art sensors, similarly to space research. The sensors to measure the ocean are either aboard a series of artificial satellites orbiting the Earth, or in instruments placed in the water. Sensors onboard satellites can measure the sea surface temperature, salinity, and sea surface height. In the water, sensors are aboard floats, mooring arrays, automated underwater vehicles, remotely operated vehicles, gliders, and seals (!). Operational oceanography is a fascinating field of research, and at its heart sits the Argo array, composed of 4000 Argo floats measuring temperature and salinity of the top 2000 m of the ocean since 2005. This array has helped oceanographers to answer important questions on ocean circulation and climate change.

Ultimately, the ocean - just like the space - brings fascination. The excitement of discovery is present both when exploring a deep canyon or a distant quasar. In the end, the ocean is also a final frontier. A frontier, however, closer to home! Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

InnovaSpace Ltd - Registered in England & Wales - No. 11323249

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed