Anthropology Of outer Space - On human/non-human relationships in the context of space science19/10/2018

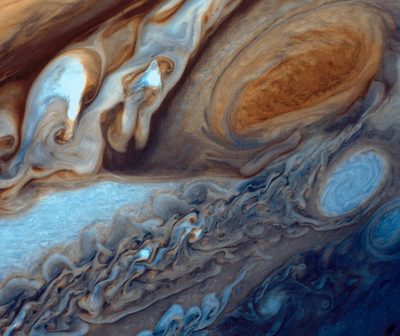

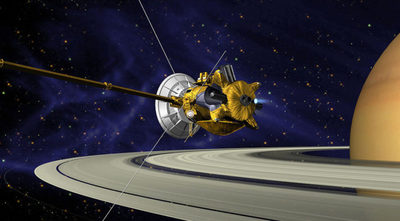

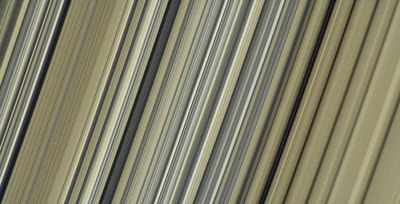

One of the first ethnographies I read when beginning my Social Anthropology Master’s degree course was Beamtimes and Life Times: The World of High Energy Physicists (1988), by Sharon Traweek. She based this seminal account on her five years of fieldwork within the almost exclusively male domain of particle physicists, studying their culture, cosmology and worldview. One fascinating aspect that she underlines is the peculiar relationship that exists between these scientists and the accelerators and detectors they use to identify subatomic particles and understand their behaviour. The accelerators are some of the largest machines built and a great part of the scientist’s life is spent inside them: hence, not just a machine, but a place. Inside these accelerators are placed the detectors, each designed and crafted by a group of scientists to find answers to their specific research questions: not just a machine, but a conceptual and intellectual fingerprint. A new particle found may unveil a big mystery about the universe and catapult a scientist to academic stardom, however, it could also prove the whole hypothesis to have been built on a misguided assumption and thus, failure. As cosmologies and careers are at stake and the data collected may promote a paradigm shift, the detectors hold the hope of access to a hidden world. Therefore, they are more like portals than machines.  Image: NASA - Extravehicular Activity Image: NASA - Extravehicular Activity There is a same high dependency on machines in space science in order to access far away or invisible events and data, and this steered my attention toward human/non-human relationships in this context. This dichotomy itself is rather a cultural construct, and in some cultures this line is not clearly defined and is variable according to the cultural context, being more or less defined in certain places at certain times. In the context of space science, it becomes even more blurred. When applied to an astronaut, for instance, this concept tends not to make sense. In fact, an astronaut only becomes an astronaut in conjunction with the spacesuit/spacecraft, or they would be unable even to reach space to become a space-traveller. In this sense, you do not have simply the human (astronaut) and the non-human (spacesuit, spacecraft), but one single entity. An astronaut is inexorably a cyborg: a hybrid of organism and machine. The close relationship of dependency between the human and non-human in space science tracks back to the 17th century, when Galileo Galilei was the first to use instruments, another specific kind of non-human, to enhance the vision and turn the invisible visible. It was a humble telescope compared to Hubble, which has already “seen” galaxies 13 billion years away, however it was able to spot the four biggest Jovian moons and the rings of Saturn. That instrument was responsible for a paradigm shift, as it provided empirical evidence to legitimate the heliocentric model offered by Copernicus the century before. Since then, the cosmos has become ever closer and more familiar. The big boost was the beginning of the space program, when engineering masterpieces began to be developed and were sent out into our cosmic neighbourhood in a quest for further answers about the origins and constituents of our solar system and the universe. These satellites, spacecraft, rovers and other robotic equipment do not belong to the same category as the ordinary, factory-produced machinery that fill the lives of most Westerners, machines that make our lives easier. They are not produced on an industrial scale; instead, they are individual pieces, designed and crafted to mirror the scientist’s quest, possibly one to which they have dedicated their entire lifetime. Anyone not familiar with this scientific culture might think of all this astronautic paraphernalia as simply being pieces of metal, in a similar way to any other machine; however, this is not the case. These machines are the scientists’ allies in outer space, “who” have been conducting fieldwork outside Earth and on behalf of the humans that built and invested in them with actions, knowledge, expectations and aims. They become the augmented extensions of humans, allowing them to reach places where the presence of people is prohibited due to the distance and inherent hurdles and dangers. And as this contingent of non-humans keeps growing and probing further into outer space, our knowledge of the universe keeps expanding and paradigms continue shifting. These machines underline the creativity and ingenuity of humans on the one hand, while also highlighting our limitations on the other. United together, however, some limitations can be circumvented. It is due to the findings of this contingent of non-human aiders on whom scientists bestow their expertise that we now know a lot more about the material and immaterial cosmic context in which we live. Until very recently, scientists continued to contemplate whether water existed on other worlds or if it might be an Earthly exclusivity. Nonetheless, data gathered by the many probes sent into orbit and those landing on other cosmic bodies suggest that water is rather universal. Evidence of water molecules has already been found on the Moon, Mars, Jupiter, comets and other satellites like Europa and Encedalus, which orbit Jupiter and Saturn, respectively, and are believed to have liquid oceans beneath their icy crust. One of the main goals of current and future space exploration is to find out about the existence of alien life in the universe, either intelligent or not. As water is fundamental to life as we know it, these discoveries fuel the hope of finding life elsewhere in the universe. Further unmanned missions will be sent to gather more data. Additionally, since the early 1990s with the help of powerful telescopes like the Kepler space telescope, there has been the discovery of thousands of other planets outside our solar system, and the hunt for Earth-like planets orbiting a star in a habitable zone or ones suitable to be terraformed has already begun. Our dependence on these machines to obtain data that provides information about the unknown and the invisible to the naked eye is so high and intertwined that it defies the limits of human/non-human relationships. In 2017, after orbiting Saturn and its moons for 13 years, the Cassini space probe dived to its death on the planet’s surface after running out of fuel, and a documentary entitled Goodbye Cassini, Hello Juno was launched to celebrate its “lifetime” of achievements. From inception to end this mission lasted 20 years, and comments made about the spacecraft by crewmembers that were interviewed when gathered at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) headquarters for the “funeral” showed that it was far more than just a machine. They were clearly all deeply grieving the loss of Cassini, treating it as if it were a person who had just passed away. Athena Coustenis, an astronomer and planetary scientists who developed one of the 12 instruments onboard, stated that “Cassini will be getting and sending data till its last breath…I’m going to cry my eyes out. It is a 20 year old friend”. For her part, Julie Webster, in charge of remotely managing the spacecraft for JPL, said the most difficult period of flying an aircraft is the first three years “because you are kind of learning what makes the personality of the spacecraft”. Indeed, Cassini showed itself to have an obedient and flawless character: “It was a great spacecraft, it did exactly what we asked it to do. All the way to the end. No surprises”, concluded Webster. The words used to refer to it, such as breath, personality and friend, clearly showed there was a relationship involving affection and trust, and that Cassini was considered a kind of human being.  Russian MIR Space Station (1986-2001) Russian MIR Space Station (1986-2001) Cosmonaut Alexander Lazutkin echoes this form of affection for the Russian space station MIR, where he spent 185 days onboard. In the documentary MIR Mortals (1998), addressing the hurdles faced by the crew in its final months, Lazukin explains the emotions felt at the final moment of its decommissioning. When the dot that represented it disappeared from the ground control screen, he said, “It was as if someone had died. And it wasn’t just me feeling that, everyone who worked on it did. It was like burying a good friend”, adding that nobody thought of it as “just pieces of metal”. If in their perception MIR died, then we can assume that it was considered to be alive. This makes perfect sense given that space stations are self-contained Earth analogue environments, on which astronaut lives depend and that offer a unique perspective of what it means to be human in an extra-terrestrial context. The robotic heralds that Western societies have been launching into space have collaborated in cosmological paradigm shifts and offered new possibilities for the future of terrestrial beings in alien worlds. If one day this becomes a reality, in keeping with the plans of the leading space agencies and even private space companies, the line between human/non-human will make even less sense, since to be human in this new context will imply permanently having/wearing non-human extensions. The line will then become irreversibly blurred. For those interested in further reading on human/non-human relationships, I leave a list of authors and documentaries that have explored this issue in greater depth than can be done in the limited space of this blog, in which I write about anthropology and outer space in a non-academic language. SUGGESTED READING/VIEWING LIST

APPADURAI, Arjun. 2006. The Thing Itself. Durham: Duke University Press. APPADURAI, Arjun. 2015. Mediants, Materiality, Normativity. Public Culture, 27(2), 221–237. doi:10.1215/08992363-2841832 HARAWAY, Donna. J. 1991. A Cyborg Manifesto, in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature), pp.149-181. New York: Routledge. HARAWAY Donna. J. 2008. When Species Meet. Posthumanities, Volume 3. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. HELMREICH, Stephan; KIRKSEY, S. Eben. 2010. The Emergence of Multispecies Ethnography. Cultural Anthropology, Vol. 25, Issue 4, pp. 545–576. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. INGOLD, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skills. London: Routledge . JACKSON, Michael. 2002. Familiar and Foreign Bodies: A Phenomenological Exploration of the Human-Technology Interface, in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp.333-346. Great Britain: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland JAMESON, Fredric. 2005. Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London/New York: Verso. KHUN, Thomas. 2012. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press . LATOUR, Bruno. 1994. Jamais Fomos Modernos. Oxford: Oxford University Press. LATOUR, Bruno. (as Johnson, Jim). 1988. Mixing Humans and Nonhumans Together: The Sociology of a Door-Closer, in Social Problems, Vol. 35, No. 3, Special Issue: The Sociology of Science and Technology, pp. 298-310. Oxford: Oxford University Press. MESSERI, Lisa. 2016. Placing Outer Space: An Earthly Ethnography of Other Worlds. Durham: Duke University Press. MESSERI, Lisa. 2017. Resonant Worlds: Cultivating Proximal Encounters in Planetary Science. American Ethnologist, Volume 44, No 1, pp. 131-142. Arlington, VA: American Anthropological Association. OLSON, Valerie A. Olson. 2010. American Extreme: An Ethnography of Astronautical Visions and Ecologies. Houston: Rice University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. PÁLSON, Gísli. 2009. Celestial bodies: Lucy In the Sky, in Humans in Outer Space – Interdisciplinary Odysseys. Pp. 69-76. New York: SpringerWien. ROBERTSON. J. (2007). Robo Sapiens Japanicus: Humanoid Robots and the Posthuman Family. Critical Asian Studies, 39:3, 369-398. New York: Routledge. TRAPHAGAN, John. 2015. Extraterrestrial Intelligence and Human Imagination: SETI at the Intersection of Science, Religion, and Culture. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. VALENTINE, David. 2012. Exit Strategy: Profit, Cosmology, and the Future of Humans in Space. Anthropological Quarterly, Volume 85, Number 4, pp. 1045-1067. Washington: George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. VAKOCH, Douglas A. 2014. Archaeology, Anthropology, and Interstellar Communication. Washington DC: Nasa Office of Communications. FILMOGRAPHY FULLERTON-SMITH, Jill. 1998. MIR Mortals, in Horizon, season 34, episode 18. BBC Two. MACDONALD, Toby. Goodbye Cassini – Hello Saturn. 2017. BBC Two. LEVINSON, Mark. Particle Fever. 2013. Athos Media. Comments are closed.

|

Welcometo the InnovaSpace Knowledge Station Categories

All

|

InnovaSpace Ltd - Registered in England & Wales - No. 11323249

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

UK Office: 88 Tideslea Path, London, SE280LZ

Privacy Policy I Terms & Conditions

© 2024 InnovaSpace, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed